Pricing Change

New pricing for orders of material from this site will come into place shortly. Charges for supply of digital images, digitisation on demand, prints and licensing will be altered.

Wanlockhead

Lead Mine(S) (18th Century), Water Pumping Engine (19th Century)

Site Name Wanlockhead

Classification Lead Mine(S) (18th Century), Water Pumping Engine (19th Century)

Alternative Name(s) Meadowfoot; Glencrieff Mine; Wanlockhead Water-powered Beam-engine

Canmore ID 46408

Site Number NS81SE 2

NGR NS 87 13

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/46408

- Council Dumfries And Galloway

- Parish Sanquhar

- Former Region Dumfries And Galloway

- Former District Nithsdale

- Former County Dumfries-shire

NS81SE 2 87 13

For lead mines at Leadhills (NS 88 14), see NS81SE 6.

For lead mine at NS 868 137 ('Bay Mine Site'), see NS81SE 13.

Water-powered beam engine at NS 8702 1313.

(Undated) information in NMRS.

Lead mines at Wanlockhead (NS 87 13): Tradition ascribes the discovery of the lead mines at Wanlockhead to Cornelius Hardskins, a Dutch gold prospector more properly called Cornelius de Vois, who was active in Scotland at the end of the 1560's, but there are documentary references to mines at Wanlock for half a century prior to that, and medieval records for the rather ill-defined area of Crawford Muir which go back to the 13th century.

From 1560 to 1604 the search for gold was the main spur to mining activity at Wanlock, but failure to find a gold seam led to the desertion of the area in 1604. The mines remained deserted until 1675 when Sir James Stansfield and others obtained a lease for nine years to work the mines. In 1691, Matthew Wilson and Andrew Well took a lease until 1710, and during that period introduced smelting with peat, and worked the Stratisteps Vein for some distance under Dod Hill. In 1710, a so-called 'London Company' took over, and in the latter part of the 18th century steam-engine pumping was introduced, but this lasted only until 1834 when lead prices slumped. and it was not until after 1850 that the industry recovered. In 1906 the Wanlockhead Lead-Mining Company took over the mines and prospered well until after 1918 when the post-war slump made it uneconomical to continue production. In 1948 the Lowland Lead Company attempted to re-open the mines, but this did not prove successful.

R Brown 1927; T C Smout 1962.

At the Bay, or Charles, Mine in Whytes Cleuch (NS 868 137) there is the stone column for another water engine and the pit of a large waterwheel. Excavations here by Glasgow University Summer Schools in 1972-4 have revealed foundations of engine and boiler houses, including the stone base for an engine built for William Symington in 1789.

W Harvey 1972; G Downs-Rose and W Harvey 1973

(Location cited as NS 87 13). There are scattered remains of lead mining and smelting around Wanlockhead village. The single-storey houses were mostly built for workers in the lead industry. The most interesting survival is a water-bucket pumping engine, of wooden costruction, with iron fittings (now under guardianship) and protected by a wooden cover.

J R Hume 1976

There are many disused lead mines in this area. The well-preserved beam engine is at NS 8702 1313.

Visited by OS (TRG) 19 July 1978.

This site has only been partially upgraded for SCRAN. For further information, please consult the Architecture Catalogues for Nithsdale District..

January 1998

Publication Account (1986)

These hills have been mined from time immemorial, possibly since Roman times, and on a commercial basis since 1680. Most of the visible remains, however, are the products of mining and smelting activity during the past two centuries. They are now cared for by a local museum trust with help from Scottish Development Department and Buccleuch Estates Ltd.

From the museum (the old smithy), a visitors' trail run through the major features of the village. The museum is located on the valley floor close to Wanlock Water, which flows north-westwards, eventually to empty into a tributary of the River Clyde.

It is down this valley that the visitor should proceed, following the track of an old narrow-gauge railway and re-crossing the bum to approach the entrance to Loch Nell Mine. This mine was fIrst opened in 1710, abandoned, then re-opened and used in its present form from 1793 to the middle of the 19th century. It continued in use as an exit from adjacent mines, and is now open to visitors over a distance of about 200m. In the second phase it was associated with a deep shaft, still terrifyingly visible within; this in turn was connected with a drainage level under Straitsteps Mine, the next objective on the visitors' trail.

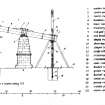

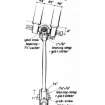

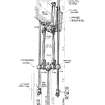

The water-bucket pumping engine above Straitsteps Mine at NS 870131 is the monumental showpiece of Wanlockhead. As befits the only known waterpowered beam-engine of its kind in Britain to survive virtually intact, it is a monument in State custody. Its task was to pump water out of abandoned workings, and it performed this function probably from the late 1870s to the early 1900s. Its design, however, was based on engines used extensively in mining industries well over a century earlier.

To operate the pump, water from a cistern was piped under the road and into a box-like bucket at the end of the beam that is held within the wooden steeple frame. The weight of water depressed that end of the beam, raising the pumping apparatus affixed to the other end. At the bottom of each stroke (about every 30 seconds) the water was released automatically through a valve into a stone-lined drainage pit, causing the pump spear to be lowered, ready to lift its next column of water up the shaft to the drainage level. Affectionately known as 'Bobbing Johns', such devices were relatively simple, and could be left to operate with the minimum of attention. Would that some water in a bucket, or a coin in the slot, could set it all in motion again!

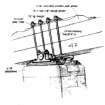

Near the pump there is the circular track of a horse-engine which was at one time used for winding ore and spoil out of the mine. From here, the trail traverses the valley to a modem plinth, which bears a reproduction of a 1775 drawing showing the mining scene from about this viewpoint The trail then recrosses the valley to the ruins of Pates Knowe Smelt Mill. When it was built in 1764 this mill was only one of a number on the Wanlock Water, but in about 1789 it was enlarged in order to smelt all the mined ore. In 1845 it was partly dismantled in order to build a new mill downstream. Excavation has revealed the outline of two 'back-to-back' furnace houses sharing a central water-driven bellows house. The cast-iron 'Scotch ore' smelting hearths are rare survivors from the 18th century, and the ore and slag hearths in the eastern half of the building have been partly restored to give an impression of their original appearance. Equally signifIcant discoveries have been made at the Bay Mine (NS 868137), the furthest point on the industrial trail. The visible remains represent successive attempts to pump water out of this area of particularly deep mines. Stone mountings are all that survive of the atmospheric steam pumping engine which operated here from 1790 to 1799. Upon the reopening and deepening of the mine (to 152.4m) after 1842, a hydraulic pump was introduced alongside a steam-powered winding engine, but even these combined arrangements could not cope with the flooding effects of torrential rains. In the 1880s an auxiliary pump was built purposely to be driven by flood water. The surviving stone-built pit shows that it must have had a big 9.1m diameter wheel, no doubt a memorable sight as it turned in the pouring rain.

There is, of course a human, as well as an industrial side to the Wanlockhead story, which is best told by the buildings in the village, by the monuments in the burial ground eNS 864136), and by the museum exhibits. The whole village is known to have been rebuilt by the Quaker Company in the decade after their lease of 1710. Again, after 1842, when the Dukes of Queensberry took a direct stake in the running of the mines and in the welfare of the workforce, the houses were rebuilt and their numbers increased. When direct ducal control ended in 1906 there were about 173 inhabited dwellings in the village and Meadowfoot Many had upper storeys, slated roofs and dressed stonework, but, a substantial proportion had steeply-pitched, heather-thatched roofs concealing boxed 'lums'. The ruins of one such terraced row can be seen by the roadside on the return journey from Bay Mine.

The community buildings were also built or rebuilt in the middle decades of the 19th century. As an institution, however, Wanlockhead Library is second only to Leadhills as the oldest subscription library in Britain. In 1756, 32 men of the village, mostly miners, subscribed to a reading society 'for the purpose of purchasing books for our mutual improvement'. The first purpose-built library was erected in 1788, and the present building was put up in 1850 to accommodate a much-expanded collection. It was last used as a lending library in the 1930s.

Main-line railways arrived in the neighbouring valleys in the mid 19th century, and a branch-line railway ran between Wanlockhead and Elvanfoot from 1902 to 1938. In the early days most lead was carted to Leith, and if the visitor follows this route on his return journey he will see the surviving evidence of rival concerns in the neighbouring village of Lead hills (NS 8814; Clydesdale District, Strathclyde Region). The mining grounds here were owned by the Hope family from the 1640s, and contributed to Hopetoun House, their grand mansion in West Lothian. The mines were closed in 1928, and, compared to Wanlockhead, the centre of Lead hills now exhibits considerably less of its industrial origins.

Information from ‘Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: Dumfries and Galloway’, (1986).

Publication Account (1986)

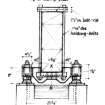

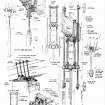

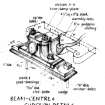

Situated at the N end of the old lead-mining village of Wanlockhead, this engine stands above a disused mineshaft on what was part of the Straitsteps Mine. It probably dates from about the last quarter of the 19th century and is believed to have served as an auxiliary pump for draining water from abandoned workings to the S. Technically defined as a water-bucket pumping-engine, its motive power was supplied by the weight of water fed into a box-like bucket at one end of the beam, which worked on a centre and carried the pumping-apparatus at the other; at the bottom of each stroke the water was discharged from the bucket through a sluice or flap-valve, thereby transmitting the primary load to the far end of the beam and causing it to move up and down alternately. An earlier engine, evidently conforming to the same working principles, was recorded in operation in the parish of Canonbie, Dumfriesshire, during the 1790s, and by that time similar engines were being used extensively on coal and metal-mines in various parts of Britain.' Today, however, the engine at Wanlockhead is believed to be the only example of its type in Britain to remain virtually intact.

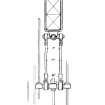

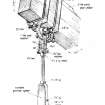

The beam, which measures 27 ft 9 in (8.46m) in length and 25 in (0.63m) by 11 1/2 in (292mm) in section, is made of two baulks of pitch-pine, strengthened by moulded wooden pad-plates at the ends and centre, and bound together by a combination of iron straps and tie-rods. Mounted on a 13ft-high (3.96m) dressed stone pillar, the beam is pivoted on a forged gudgeon-block set in cast-iron plummer-blocks and split-brass bearings. The plummer-blocks are secured to their mountings by long anchor-bolts extending through the masonry to the base of the pillar; the beam itself is locked on to the gudgeon-block by means of a lower clamp-plate whose soffit is shaped and recessed to fit round the seating. At the power end the bucket-rod is attached to a crosshead-slide which moved up and down on guide-rails held in a wooden steeple-frame; the slide in its turn is connected to the beam by two link-rods and a cross headcoupling. In general, the various iron forgings and castings are made to a high standard, and all the critical moving parts are held in brass bearings.

No trace of the bucket remains, but the stone-lined pit into which it descended, measuring 5 ft (1.52m) in depth and 4ft (1.22m) by 2ft 3in (0.69m) in area, preserves its drainage outlet at the bottom, and also the iron-clad wooden rails for steadying the bucket when in motion. An 8 in-diameter (203mm) iron plate with raised rim, held loosely on the end of the bucket-rod by a large iron wedge, may have been part of the water-release valve mechanism attached to the bucket. Depending on the position of the bucket on the rod, the related lengths of the bucket-rod and steeple slide-rods (respectively 11 ft 2 in (3.40m) and 10 ft (3.05m) between centres) would allow an engine-stroke of approximately 7ft (2.13m). The other end of the beam overhangs the mine-shaft and carries the remains of a Sin-square (127mm) wooden pump-spear, which is connected to the beam by a shackle and crosshead-coupling.

Water for working the engine was collected in a cistern situated on the hillside above and then piped into the bucket at a level coinciding with the head of the stroke. On the evidence of a photograph taken c.1900, the engine was then in a state of disuse, but at that time it still retained a sheer-leg structure over the mine-shaft, used apparently in association with a nearby horse-gin for the handling of materials and pumping-apparatus.

Information from ‘Monuments of Industry: An Illustrated Historical Record’, (1986).

Field Visit (13 May 2012 - 28 May 2012)

NM 819 002 (centred on) The overall aim of the research project is to identify prehistoric copper mining in Scotland. The survey began, 13–28 May 2012, by visiting sites where probable hammerstones have been found. Sites visited included Barhullion, Balcraig, Kirklauchline and Wanlockhead all in Dumfries and Galloway, an area where the discovery of a copper ore (bornite) outcrop in a recent quarry at Kirklauchline was of particular interest.

Several other copper mining districts in SW and central Scotland were also visited, including the Tullich Mine at Loch Tay (Perth and Kinross), different sites in the mining district of Wanlockhead/Leadhills (Dumfries and Galloway/South Lanarkshire), Mary’s Mine/Tonderghie (Dumfries and Galloway) and the Kilmartin Copper Mine (Argyll and Bute). Around Bridge of Allan in the Ochill Hills are several copper outcrops where the late medieval Airthrey Hill Mine spoil heaps (Stirling) are easily accessible and still contain a good quantity of copper ores. In Argyll and Bute the mining remains of Abhain Strathain/Meall Mor, at Kilfinan (Murder Lode) and Castleton/Castletown (SE of Lochgilphead) revealed good ‘grey copper ores’, especially at Castleton where the mineralised vein outcrops are easily seen on the shore. In addition the 2012 survey discovered another ore vein along Kilmartin Glen, at the Duntroon Hillfort. The mineralisation is very interesting because of its proximity to numerous archaeological sites.

Further investigation is planned in the area and on other old mining sites in Scotland for 2013. A collection of ore samples has been stored at the National Museums of Scotland, which will hopefully be enlarged in the future to provide a reliable database for investigations, such as the comparison of trace element and lead-isotope ratios in the samples with those found in prehistoric metal objects.

Archive: National Museums of Scotland

Funder: German Archaeological Institute, Department Rome

Daniel Steiniger, German Archaeological Institute, Department Rome

2012