Traprain Law

Fort (Prehistoric)

Site Name Traprain Law

Classification Fort (Prehistoric)

Alternative Name(s) Dumpender Law

Canmore ID 56374

Site Number NT57SE 1

NGR NT 5800 7470

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/56374

First 100 images shown. See the Collections panel (below) for a link to all digital images.

- Council East Lothian

- Parish Prestonkirk

- Former Region Lothian

- Former District East Lothian

- Former County East Lothian

NT57SE 1.00 580 747

For cairn and cup-and-ring markings found on Traprain Law, see NT57SE 87 and NT57SE 88.

For specific categories of find, see the following entries:

NT57SE 1.01 c. 580 747 Amber beads; glass beads; jet beads

NT57SE 1.02 c. 580 747 Bone objects

NT57SE 1.03 c. 580 747 Bronze hoard (possible); socketed bronze axes

NT57SE 1.04 5794 7460 Carbonised grain

NT57SE 1.05 5792 7461 Cinerary urns; accessory cup

NT57SE 1.06 c. 579 746 Crucibles

NT57SE 1.07 c. 579 746 Flint arrowheads

NT57SE 1.08 c. 580 747 Flint scrapers; flint knives; flints

NT57SE 1.09 c. 580 747 Glass armlets; jet armlets

NT57SE 1.10 c. 580 747 Metalwork

NT57SE 1.11 579 7646 to 583 748 Microliths

NT57SE 1.12 c. 580 747 Pottery

NT57SE 1.13 c. 580 747 Pottery

NT57SE 1.14 c. 580 747 Querns

NT57SE 1.15 c. 580 747 Roman coins

NT57SE 1.16 c. 580 747 Roman glass

NT57SE 1.17 c. 580 747 Roman pottery

NT57SE 1.18 5793 7458 Roman, silver hoard

NT57SE 1.19 c. 583 748 Silver Chain

NT57SE 1.20 c. 580 747 Stone axes

NT57SE 1.21 c. 580 747 Stone balls

NT57SE 1.22 c. 580 747 Stone discs

NT57SE 1.23 c. 580 747 Stone moulds; clay moulds

NT57SE 1.24 c. 580 747 Stone objects

NT57SE 1.25 c. 580 747 Whorls

NT57SE 1.26 c. 581 746 Pottery; glass; jet armlet; stone disc (1993)

NT57SE 1.27 c. 581 746 Bracelet; implement; mount (2005)

Two bronze spiral finger-rings.

E J MacKie 1971.

Bobble-headed pins, and mould for knobbed spear-butt.

L Laing and J Laing 1986.

Excavation (1914 - 1923)

Excavations were undertaken on Traprain Law by Alexander O Curle (Director of the National Museum) and James E Cree between 1914 and 1915, and again between 1919 and 1923.

Field Visit (1914 - 1923)

Traprain Law,or Dumpender Law, lies 1 ½ miles to the south-south-west of the small town of East Linton in the parish of Prestonkirk. It is situated in an undulating terrain, which swells gradually upwards from the East Lothian seaboard to the Lammermuirs. Its summit – 710 feet above sea-level and 360 feet above its base – commands a wide prospect ranging from the Pentland Hills round by Gullane Hill and North Berwick to Dunbar, while to the southward the Lammermuirs fill the horizon.

[For a full description of the fort at Traprain and the finds recovered during its excavation, see RCAHMS 1924, 94-99. The article was most likely penned by A O Curle, the excavator of Traprain and Commissioner to RCAHMS]

RCAHMS 1924, visited 1914-23.

Excavation (April 1947)

At Traprain Law a small scale excavation directed by Dr Bersu for the Society of Antiquaries [of Scotland] was devoted to (a) two sections through the oppidum rampart and the underlying terrace on the W side of the hill and (b) trial trenching on the summit of the hill near the Trigonometrical Station. One section was cut near the westernmost of the two main entrances and the other further S. The rampart is of the same dimensions and construction as found by Mr Cruden but wheras the E end of the rampart overlies Roman hearths at its W end it is built on top of the big terrace bank, which is a continuation of the low platform of the powder magazine on the N side of the hill. This terrace bank, which at one time formed the main defence of the oppidum, was disused by the time the rampart was erected over it. It is constructed of material scraped up from the inhabited area inside it, including miscellaneous refuse, fragments of pottery and querns, and bronzes, and owning to the steepness of the slope, probably revetted with timber. The pottery shows that the terrace bank is not earlier than the late 3rd or 4th centuries (though there are surface indications of an earlier terrace bank outside it on the W) so that the Cruden rampart is most probably of Dark Age date and possibly connected with the remains of rectangular buildings on the summit. The two large entrances cut in the Cruden rampart and the terrace bank on the N may even be medieval, although they may occupy the sites of earlier entrances. The results of the excavation and the wealth of structural remains still unexcavated suggest that Traprain has a much more complicated history than has hitherto been assumed, and that without a detailed survey of the entire hill and extensive excavation, little further information can be gleaned about this key site for the Scottish pre- and early history.

DES 1948, 5

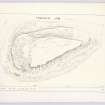

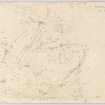

Measured Survey (April 1955)

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments (Scotland) undertook a plane-table survey of Traprain Law in April 1955. Working from a total of 120 stations, the team produced a plan at a scale of 2 1/2 inches to 100 feet (approximately 1:480). With the permission of the Commissioners, a reduced version of the plan was published by their archaeologist RW Feachem in 1958.

Field Visit (5 November 1962)

The remains of the hill-fort are generally as described above [OS desk-based assesment c.1962]. The modern quarry at the NE end of the Law is gradually being extended and is destroying the NE defences. No trace was seen of the south portion of the rampart Cruden 2 and also no traces were seen of the vestigial rampart Cruden 2a. At approximately NT 5793 7461 is a dry-stone lined subterranean passage 5.6m long by 0.6m wide and 0.9m deep. Its main axis lies approximately N-S and it is partially covered by stone lintels. No trace can now be seen on the ground of the hut circle shown to the E of the summit on Feachem's plan, nor of the foundation shown on same plan at the base of the Law at its SW end. No further information was found to establish the possible site of St Monenna's Church, nor the site of the 16th century beacon.

Revised at 25".

Visited by OS (WDJ) 5 November 1962

Desk Based Assessment (1962)

Traprain Law is an isolated hill occupying a commanding position 710ft above sea level. The SE flank is protected by a 200ft high vertical cliff which breaks away to the SW into lower but still steep crags. The NW flank is defended by a broken rocky surface 50ft high, and above this is a gradual slope to the summit which lies close to the precipice on the SE side (RCAHMS 1924, 94-9).

The old name of the hill is Dumpender Law which, in the form Dumpelder is first met with in 'The Life of St Kentigern' written probably in 1180 (Curle 1915). It also occurs as Dumpeldar in a pre-1368 charter, and in 1455 as Dunpendar Law (RCAHMS 1924).

There is a record of a beacon having been kept in readiness on Dunprendar Law in 1547 (RCAHMS 1924).

The artificial defences consist of:- (compiled from RCAHMS 1924; Cruden 1940; Feachem 1958).

a) A 6ft stone revetted rampart stretching from the South end of the vertical cliff round the top edge of the SW crags to a rocky outcrop on the NW flank where it is deflected up the hill and continues on to join the NE end of the vertical cliff (known as Cruden 3).

b) A rampart on the lower edge of a terrace on the N flank of the cliff (Cruden 1). Only slight remains.

c) A rampart from an escarpment on the western part of the hill which runs north under the main rampart (Cruden 3) and then roughly parallel to it along the N edge of the summit (Cruden 2).

d) Another vestigial rampart (Cruden 2A) running for some distance approximately parallel with and slighly to the north of Cruden 2, but apparently parting from it at the west end.

e) Tenuous remains which may be those of a wall, single-faced rampart, or even a road, running for a distance of some 800ft along the main axis of the hill north of the summit.

The area enclosed by the main rampart is approximately 800 yards by 300 yds, about 32 acres. It contains remains of of cirular huts 'analogous to other in the area' and 'more interesting' multi-roomed houses with sub-rectangular rooms 'similar to the undated long houses which appear on Northumbrian sites'. There were apparently four entrances through the main rampart, all on the west sides, and one entrance to the terrace at its NE end where it adjoins the modern quarry (RCAHMS 1924).

Excavations were carried out in 1914-15 (Curle 1915; Curle and Cree 1916) and in 1919-23 (Curle 1920; Curle and Cree 1921; Cree and Curle 1922; Cree 1923; Cree 1924) in the interior (with limited digs at one of the gateways and at the 'reservoir') by A O Curle and J E Cree. The ramparts were excavated by S H Cruden in 1936 (Cruden 1940) and by G Bersu in 1947 (Archaeol News Letter 1948).

The finds from the excavations went to the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland [NMAS], Edinburgh and in general consisted on some Neolithic implements, a number of Bronze Age implements and ornaments, and a great quantity of Romano-British material. One or two mediaeval items were found and seem to have been related to the beacon keeping.

The following particular items were also found:-

The Traprain treasure. This famous hoard of Roman silver plate was found on 10 May 1919. With it were two coins of Honorius indicating that it was probably deposited in the early fifth century. Its style and general character indicating that it had come from the continent probably as loot. It is fully catalogued and discussed by A O Curle (1923)

Early Bronze Age Cremation Burial. This was found during the 1920 excavations. There were 4 cinerary urns which had probably all been inverted, under one of which were incinerated human remains, and a small incense cup (A O Curle and J E Cree 1922).

Silver Chain. A massive double-linked Silver Chain of the Early Christian period was found near the quarry between the 600 and 700ft contour lines in January 1938. It is tentatively dated 6th - 8th century AD (A J H Edwards 1939).

Sculptured Rock Surfaces. Three areas of sculptured rock surface were found during quarrying in 1931. They comprised cup and ring marks, intersecting lines and tectiform symbols, and in one area a stepped cross of 14th century date indicating that at that date the rock markings had been exposed and exorcised (A J H Edwards 1935). Fragments of the sculptured rock went to the NMAS.

The results of the excavations up to 1923 are summed up in RCAHMS (1924) and, so far as the Roman Britain side is concerned, by James Curle in 1931 (Curle 1932). The latter found that the main occupation probably started towards the end of the 1st cent AD and that the finds were typical of those from native sites during the Roman occupation. He noted that the coins fell into two groups, Mark Antony - Faustina the Elder, and Gallienus - Honorius.

Cruden's excavations showed a second century terminus post quem for the main rampart on the evidence of a piece of Terra Sigillata type 18/31 found under a hearth, which in turn was under the rampart, and also demonstrated that the main rampart was later than and distinct from the slighter rampart on the north (S H Cruden 1940).

Bersu considered that the earlier rampart where it underlay the main rampart was no earlier than the late 3rd - 4th century as it had been constructed from material scooped up from the interior including pottery up to that date, and therefore that the main rampart was 'probably of Dark Age date' (Archaeol News Letter 1948).

A H A Hogg (1951), reviewing Traprain Law in a Votadinian context, regards it as having been occupied by inhabitants on good terms with Rome up to about AD 155 after which it may have been abandoned (? due to an attack on people) friendly to Rome after the withdrawal of troops by Albinus). He thinks that the occupation was probably resumed after the Severan restoration and continued up to the 6th century, because Dunpeledur is listed as one of the places at which St Monenna founded a church, because of the dating of the Silver Chain, and because the multi-roomed houses can by analogy with those at Ingram Hill (Northum 27 SW) be considered post-Roman.

In a survey of the metalwork from the 1914-23 excavations Miss E Burley (1958) finds that Traprain Law was occupied in the Bronze Age circa 6th century BC and continued to be occupied, with the possibility of a gap between the end of the Bronze Age culture and the beginning of the Iron Age culture, up to about the middle of the 5th century. She found no characteristic Dark Age objects and recalls that St Monenna is traditionally supposed to have selected deserted hills for the sites of her churches.

R W Feachem (1958) reviews the evidence for dating the ramparts and advances a hypothetical sequence of construction in 4 or 5 phases.

The first phase possibly marked by the tenuous (?) rampart along the main axis of the hill, giving a defended area of about 10 acres. The next (and first recognisable) consisting of Cruden 2 enclosing an area of about 20 acres. The next comprising Cruden 1 extending westward on the line of Cruden 3 after their junction, enclosing an area of 40 acres, and the final stage comprising Cruden 3. He considers Bersu's dating unlikely and disposes of the evidence on which it is based by suggesting that the material came from a reconstruction of the earlier rampart after barbarian attack in 300 AD. He is of the opinion that the main rampart may have been constructed in 370 AD when the Votadini became 'foederati'. He regards the claim for Dark Age occupation of the hill as 'not proven'.

Information from OS Recorder c.1962

Sources: RCAHMS 1924; A O Curle 1915; 1920; A O Curle and J E Cree 1916; 1921; J E Cree and A O Curle 1922; J E Cree 1923; 1924.

Publication Account (1963)

Traprain Law bulks 'like a harpooned whale' on the East Lothian coastal plain to the N of the Lammermuir massif. It rises 500 ft from the ground below, the N, E and S flanks falling steeply, but only the latter at all precipitously, and the W face sloping gently enough to have accommodated a great many timber-framed buildings. The sequence of pre- and proto-historic events that must have taken place on this conspicuous and majestic landmark was first revealed after a party of workmen had been employed to dig up a considerable area of the principal terrace on the W slope, during the first quarter of the present century. The relics thus obtained included the spectacular hoard of Roman silver (NT57SE 1.18) that has been published seperately, together with a great mass of native material which indicates that the hill was in occupation for a period of about 1000 years from the middle of the first millennium BC.

During this time several sets of defensive works succeeded each other to enclose different amounts of the surface of the hill. No remains of the earliest are apparent, but it can be safely assumed that one or more palisaded enclosures were formed on the W slope and on the summitt before the first ramparts and walls appeared. The length of the occupation has had the effect of blurring and obscuring the earlier versions of these more substantial works, but it is possible to follow part of what may have been the first of them, a scarp strewn with occasional grass-covered stones and boulders which borders the summit area on the N. This would have enclosed an area of about ten acres, comparable to the so-called minor oppida of Tweeddale, among them the earliest phase of Eildon Hill North (NT53SE 57).

It is suggested that the next structural development took in a further ten acres of the gentle slope immediately N of the enclosure just described; this can be traced by the rather tenuous ruins of a rampart bordering the true summit to the W and NW, and by extensions of the same nature which run along the brink of the descent to the N.

The third major reconstruction is deemed to have taken in the terraces and slopes on the W face of the hill, enlarging the enclosed area to 30 acres and so producing the second largest hillfort or oppidum in Scotland, indeed in the whole of North Britain, except Stanwick in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Yet another enlargement followed, in which the N face of the hill was also incorporated and the size of the oppidum reached 40 acres, comparable to the Eildon Hill oppidum at its largest.

The 40-acre capital of the Votadini must have been a veritable town, containing numerous inhabitants employed upon industries such as metal-working, as well as on agriculture, stock-breeding and trading with the South, probably by the east coast sea route. It has been inferred that the Votadini were in treaty with the Romans, for as far as can be seen at the present time, the successive later reconstructions took place after Pictish, rather than Roman, destructive expeditions. The 40-acre wall or rampart may have been built in the first century AD, shortly before the local arrival of the Romans in the 80's, and it may have been reconstructed at least twice, after such events as the Pictish raids of 197 and 297.

The final form of the oppidum is represented by the most impressive remains on the hill today. A stone-faced, turf-cored wall (3500 ft in length and 12 ft in thickness) was laid out to relinquish the N face of the hill, and so to reduce the area enclosed to 30 acres again. As this wall overlies almost all the other ramparts at one place or another, it is naturally the first object to strike the eye of the visitor, and parts of it are in a good enough state of preservation to reward examination. It has been suggested that the town defended by the last wall began in locally sub-Roman times, in the last half of the fourth century AD, and that it lasted perhaps until the Saxons came.

The long and virtually continuous occupation of the oppidum on Traprain Law, its degree of sophistication when compared to the bucolic settlements all about, and its more than local standing make it by far the most important place in the late prehistory and early proto-history of Scotland, and of a wider area including NE England, while by reason of the supposed accommodation the Votadini had made with the Romans, it has a unique place as a 'free' British town in Roman times. The only other oppidum of comparable size, that on Eildon Hill North, appears to have been deserted during the Roman period and never to have been used again, and the same probably applies to all the few other oppida that have been recorded in the north. There can be no doubt that here, if nowhere else in North Britain, excavations on a generous scale carried out over a considerable period would be vastly rewarding, with reference to a thousand most interesting and formative years.

R W Feachem 1963.

Aerial Photography (1967)

Oblique aerial photographs of Traprain Law, East Lothian, photographed by John Dewar in 1967.

Aerial Photography (April 1970)

Oblique aerial photographs of Traprain Law fort and Standingstone enclosure, taken by John Dewar in April 1970 (sortie 5716).

Aerial Photography (1970)

Oblique aerial photographs of Traprain Law fort taken by John Dewar in 1970 (sortie 5718).

Note (29 November 1972)

Classification of Roman material.

Information from OS (ES) 29 November 1972

Source: A S Robertson 1970.

Note (17 September 1973)

A bronze coin of Constantine the Great (306-337 AD), minted at London was found not far outside the entrance to the hill-fort by two Edinburgh schoolboys, A Ferguson and A Hogg, 19 September 1955, and was donated to NMAS.

Information from OS (ES) 17 September 1973

Source: Proc Soc Antiq Scot 1958; A S Robertson 1963

Publication Account (1975)

Traprain Law hillfort, which went through a series of reconstructions, was extensively excavated at intervals between 1915 and 1921 but the sequence of layers that yielded large quantities of finds could not at that time be adequately defined or related to the ramparts. Subsequent careful surveys and limited excavation of the ramparts have established a structural history for the hillfort, but how the finds relate to this is still not clear. The situation of the site is commanding, overlooking a wide stretch of fertile farmland and having formidable natural defences. In Roman times the surrounding territory was that of the Votadini, whose capital was doubtless Traprain Law.

The finds recovered from the excavation indicate a millennium of possibly continuous occupation from the Late Bronze Age (in the seventh or even eighth century BC) down to post-Roman times. The site produced rare examples of Late Bronze Age metalwork (NT57SE 1.03) - socketed axes, knives, chisels, spears and so on - apparently in association with pottery (a plain gritty ware) and stone hut sites. Judging by other dated examples, there may well have been a wooden palisaded enclosure on top of the hill at this time. The great mass of objects recovered from the upper levels belong to the pre-Roman Iron Age and to Roman times, and include a spectacular hoard of late Roman silver (NT57SE 1.18), which, with many of the other finds, is on display in the National Museum in Edinburgh. In general, the ramparts run round the hill from S through W to the NE end; the long and straight precipitous edge on the SE side appears to have been a sufficient protection on its own, and lacks ramparts.

The defences of the earlier phases of the hillfort are naturally inconspicuous, having being robbed of material for the later ones. The most striking to the visitor is the latest, which is a wall 3.7m thick with a turf core faced with stone; this extends for some 1070m around the hill, encloses about 0.12 sq km (30 acres) and overlies all the other ramparts. It seems to represent a reduction in size of the oppidum from the previous phase and, belonging to the latest phase of occupation, may have been used until about the middle of the 5th century.

The previous rampart evidently enclosed an even larger area of about 0.16 sq km (40 acres). It followed the course of the final rampart except along the N face of the hill, diverging from the former at the W end and running diagonally down the N slope towrds the quarry. Near the quarry is an entrance through this rampart, near which relics of the first century AD were found in 1915; the 40-acre oppidum may have been built early in that century but a construction several centuries earlier is easily possible. The site must have been a barbarian town at that time, with numerous thatched wooden or stone-walled huts, and many specialist craftsmen plying their trade. Bronze craftsmen were concentrated there, judging by the numerous ornaments of that metal (many enamelled) that were found. Many iron weapons and agricultural implements give a valuable picture of the equipment of a wide section of the community.

The previous (second) phase of the hillfort seems to have occupied the same area as the fourth but its remains are naturally difficult to disentangle from those of the latter. The earliest fortifications appear to be represented by the now-incomplete remains that run along the W end of the highest part of the hill, on the crest of the slope. This would elsewhere have followed the course of the second and fourth lines of defences and perhaps enclosed an area of 0.08 sq km (20 acres). Since the trenches that revealed the Late Bronze Age settlement were further west at the foot of this slope, it would seem that the first hillfort is later than that phase.

There is no doubt that if Traprain Law was stratigraphically excavated, the sequence of defences worked out and linked with the sequence of finds, it would be a key site for the archaeology of northern Britain.

E W MacKie 1975.

Excavation (1984)

Excavation of a short sector of the lower rampart at the E end of Traprain Law revealed at least three phases in the construction commencing with two paralllel palisade trenches replaced by a bank and a ditch. Over these a further earthen bank with an outer stone revetment was built after a period of abandonment. This later refurbishment may be connected with an area of large flat slabs set tightly together on the line of the bank and a posthole, suggesting the possibility of a gateway.

Publication Account (1985)

Traprain Law dominates lowland East Lothian. Though quanying steadily erodes the north-east part of the oval, volcanic 'hog-back' or 'harpooned whale', it remains impressive and craggy, an almost unassailable fortress with a known occupation of at least 1000 years.

One of its most prominent features is the 1.07km long rampart of turf, faced with stone. Some 3.6m thick, it encloses some 12 ha on the top and west side of the hill where it overlies its predecessor which then skirted lower round the north side (and now ends abruptly at the quany). This extended enclosure, covering 16 ha, may have been built in the mid 1st century AD, shortly before the Romans arrived cAD 80; the reduced, later sort dates from late 4th century the post-Roman capital perhaps of the Votadini.

A marginally later, early 5th century date is given for the remarkable hoard of Roman silverware (now in the National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh). It consists mainly offragments of over 100 different objects-bowls, spoons, wine-strainer, flagons, dishes, plates-deliberately cut up, it would seem, bent and flattened, ready for melting down. Loot perhaps from a rich Roman household in England or Gaul? A Roman bribe or payment for military service? A reflection of the short-lived or two-faced nature of the 'peace'? At any rate it had been buried for security in a pit below floor level. The Christian motifs on some of the silver, whilst in no way suggesting Christianity at Traprain, nonetheless indicate the potentially Christian nature of so much of the late Roman world.

This Votadini capital, if such it was, may have been occupied until the arrival of the Angles in or after the mid 7th century AD; more likely, given the excavated finds and the state of the surviving defences, it was abandoned c mid 5th century with power transfering further west, perhaps to Edinburgh.

The earlier phases of occupation at Traprain are less easy to pinpoint Bronze socketed axes and other items have been dated to the 6th-7th century BC, whilst pottery urns for cremation burials might suggest an occupation as early as c 1500 BC. There is little to see on the ground, though the settlement sequence may have started with a 4 ha palisaded enclosure on the summit and west slope, added to on two subsequent occasions with further 4 ha enclosures.

Some 300m south-south-west ofTraprain at NT 578741, a 2.5m high standing stone is known traditionally as the Loth stone. Tradition suggests that King Loth was the eponymous hero of Lothian, and had his base on Traprain!

Information from 'Exploring Scotland's Heritage: Lothian and Borders', (1985).

Excavation (1999)

NT 582 746 This report covers the results of the first two seasons of fieldwork conducted as part of the Traprain Law Summit Project (TLSP). The work was carried out between March and October 1999 principally by members of the Departments of Archaeology of the University of Edinburgh and the National Museums of Scotland. Traprain Law, East Lothian, is amongst the largest of Scotland's hillforts. It has long been recognised as one of the most important prehistoric sites in Scotland. The Summit Project is designed to increase our understanding of the nature of past human activity on Traprain Law by examining the series of poorly understood and fragile remains on its summit. The project is intended to provide information which will aid its future management as well as addressing its present threats.

The project defines the summit of Traprain Law as the area enclosed by the inner rampart to the N and W. and by the steep southern crapgs to the S and E. A range of upstanding features has been recorded previously on the summit, but they have recieved remarkably little archaeological attention. Work in the past has tended to focus on the outer defences and on the settlement concentration on the W plateau. A detailed set of research questions were formulated these primarily relate to establishing the character and date of the few upstanding features on the summit areas. Another important area was assessing the archaeological potential of the apparently blank areas between these features, all set within an overall framework of contributing to site management. A wide range of fieldwork techniques were applied to complete the research aims, these include geophysical surveys, metal detecting, topographic and contour survey, condition survey, sample excavation and paleoenvironmental assessment. Separate reports will be produced for the condition survey and topographic/contour survey elements, once fieldwork is completed in 2000.

The results obtained so far are in many cases provisional and await further information to be obtained in 2000. Geophysical survey has proved largely ineffective as a prospective tool. Though resistivity profiling has been shown to provide interpretable results when applied to surface structures. Similarly, metal detecting proved largely ineffective at detecting buried artefacts. This suggests that the threat from illicit metal detecting might be less severe than some fear. Although it should be remembered that the effectiveness of metal detectors will vary seasonally as ground conditions change. The excavations have provided much useful information. The examined circular stone built enclosures are interpreted as being of post-medieval origin and may be the boundaries of plantations referred to in a 18th century account. A rectangular enclosure on the summit, previously investigated by Bersu, appears to be medieval in origin. An area of early Christian activity has been tentatively defined in this same area. Results of work conducted in the pond or tank, previously examined by Cree, is at the moment inconclusive. Good potential for waterlogged preservation has been established and a boundary bank has been defined on its N side. The so called 'summit enclosure' boundary which was previously reguarded as lying within the visable enclosure sequence, has now been established at one point as a wall with structural affinities to the late Cruden Wall. One potential alignment of the inner rampart has been established instead as a wall fronting a probable terrace of Roman Iron Age date. Buried archaeological remains have been identified in all the so called 'blank areas' tested to date. A diverse range of artefacts from Neolithic stone axes to Medieval pottery has been recovered. The reports argues that the most interesting find is a possible Roman seal box lid, this find may have a large impact on our understanding of the extent of literacy in native societies in contact with the Roman Empire. The scatter of later prehistoric pottery from deposits across the summit area suggests extensive activity of this date.

The paleoenvironmental studies that have been conducted have established the homogeneity of almost all soils examined so far across the hilltop. The only exception top this are the soils present within the pond. The potential for obtaining well provenanced paleobotanical data and for the preservation of organic remains is considered poor apart from those deposits in the pond. The results so far have been used to shape sampling priorities and research questions for fieldwork in 2000.

The work conducted in 1999, despite its small scale, has produced a number of important results. The so called '10 Acre Enclosure', which has been presumed in the past to be the oldest enclosure on the Law, has been shown to be defined by a wall incorporating dressed slabs on both its inner and outer faces, there are no indications that it had a turf superstructure. No dating evidence was found though the use of dressed stone is indicative of it being of a Roman Iron Age date. The nature of its construction has parallels with the late Roman Cruden wall. There is nothing to suggest that the '10 Acre Enclosure' represents a particularly early element in the enclosure of the hilltop.

Concerning the inner rampart or '20 Acre Enclosure' trench 6 did not add any knowledge beyond that collected from Cruden's excavations. Trench 7 dissociated the stone alignment there from the inner rampart and showed it instead to represent a formal demarcation of the terrace on the hill, apparently during the Roman Iron Age. It appears that an area previously used for settlement was delimited by a terrace wall, possibly for the construction of a high status Roman Iron Age Structure.

The excavations on the circular and rectangular structures on the summit show that the central and W stone structures are of relatively recent, perhaps 18th century date. The rectangular enclosure seems to be medieval but its pupose remains unclear. Within the enclosure are the remains of a possible long cist, which is presumably for the burial of a child. This may indicate an Early Christian presence. Unstratified finds clearly indicate the presence of later prehistoric activity across the summit though no features of this date were definately encountered. The trial excavation on the pond show that some waterlogged deposits do survive. As yet too little work has been done to assess their importance or to assess whether the pond was artificially formed. There is a deliberately constructed bank along the pond's N side with material behind it, this area therefore may be an important one for the survival of later prehistoric deposits on the summit.

Both geophysical and metal detecting survey proved to be of little use, however small scale excavation has been shown to be extremely helpful in tracing the presence of human activity on the summit. Resistivity profiling was found to be successful in characterising a number of archaeological features. The work completed with provide useful calibration data for use in surveys of monuments that cannot be excavated. This work will be expanded on in the 2000 fieldwork.

There appears to be significant destruction to the monuments caused by rabbit activity. Much of this damage is apparently 'historic' but the present infestation of the hill shows the process to be continuing. Present management regimes cannot completely eliminate the problem and therefore the deposits on the Law must be considered as under a medium term threat of destruction. A further threat to the archaeology of Traprain Law is fires, there have been at least two major fores in the last 15 years. Given the popularity of the hill with tourists the deposits on the hill can be regarded as under a medium term threat of destruction from fire. The lack of effectiveness of metal detecting may mean that the threat posed by illicit metal detecting is reduced. However more testing during other seasonal conditions is needed to confirm this idea. However, the large hole dug into the central stone structure seems to have been dug in response to a metal detecting signal and this highlights the extreme local damage that can be caused. Most vandalism on the site is aimed at the central circular stone structures and the modern summit cairn. The project has seen that this situation, though regrettable is not causing major archaeological damage and can be managed by the ad hoc repair of superficial damage. Path erosion, investigated only in Trench 7, can be seen to be causing medium term dmage in particular areas. Given the site's importance perhaps excavation then the installing of more formal paths should be considered. Stock damage is a factor more prevelant on the larger ramparts though this factor was not specifically examined in 1999.

The Traprain Law Summit Project is intended to be undertaken over two years. During 2000 further survey, excavation and specialist reporting is planned.

Sponsors: Funding was provided by: Munro Lectureship Committee Fund, University of Edinburgh; Russell Trust; Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Help in kind was offered by: Centre for Field Archaeology, University of Edinburgh; Department of Archaeology, University of Edinburgh; Department of Archaeology, National Museums of Scotland

NMRS MS/726/177 (October 1999); I Armit, A Dunwell and F Hunter 1999

Artefact Recovery (2000)

NT 582 746 A number of artefacts were recovered casually in rabbit-damaged areas, disturbed from deposits under the Cruden Wall in the SW corner of the site. They include Roman pottery and a fragment of a stone cup/lamp. These were non-claimed as Treasure Trove and donated to NMS. A fragment of a coarse stone object of uncertain function was found at the base of the Law, on the S side, during drystone dyking work. Claimed as Treasure Trove (TT 88/99) and allocated to NMS (GV 1603).

F Hunter 2000

Excavation (2001)

NT 582 746 The final phase of the Traprain Law Summit Project (DES 2000, 29) involved excavation of a 1 x 1m test pit to assess the nature of deposits in the pond on the summit. This revealed deposits up to 1.1m thick over bedrock. The lowest layer was a grey clay, with darker organic-rich layers above. Most of the deposits were waterlogged and preservation was good. Quantities of bone and later prehistoric artefacts were recovered, and samples for environmental analysis taken.

Sponsors: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Society of Antiquaries of London, Russell Trust, Munro Lectureship, Queen's University Belfast, NMS.

I Armit, M Church, A Dunwell and F Hunter 2001

Excavation (2001)

NT 582 746 The final phase of the Traprain Law Summit Project (DES 2000, 29) involved excavation of a 1 x 1m test pit to assess the nature of deposits in the pond on the summit. This revealed deposits up to 1.1m thick over bedrock. The lowest layer was a grey clay, with darker organic-rich layers above. Most of the deposits were waterlogged and preservation was good. Quantities of bone and later prehistoric artefacts were recovered, and samples for environmental analysis taken.

Sponsors: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Society of Antiquaries of London, Russell Trust, Munro Lectureship, Queen's University Belfast, NMS.

I Armit, M Church, A Dunwell and F Hunter 2001

Artefact Recovery (2001)

NT 582 746 A saddle quern fragment and a folded piece of lead were found on the slope up to the NW corner of the western plateau of Traprain Law, and two later prehistoric pot sherds were found in rabbit-disturbed material from under the Cruden Wall at the SW corner of the site. All were donated to NMS.

F Hunter 2001

Archaeological Evaluation (November 2003 - December 2003)

NT 580 747 Following an extensive fire in late summer 2003, assessment of the damage was undertaken between November and December 2003. The area below the Cruden Wall on the W side, and the southern edge of the hill from the SW corner along to the E end, have all been damaged. A walkover survey revealed significant new information about the ramparts and terraces of the site, since stonework was markedly more visible than normal because of the loss of soil and vegetation. Some previously un-noted terraces were identified, and revetment walls were revealed on many others. The defensive system appears more complex than has been noted before. A total of 44 test pits were excavated to assess the scale of damage, which varied considerably from superficial to severe (the soil converted to ash at depths of up to 0.4m). Fieldwalking of the burnt areas produced a scatter of finds, including samian and Roman glass.

Sponsors: HS, NMS.

F Hunter and A Dunwell 2003.

Archaeological Evaluation (2003)

NT 580 747 Following an extensive fire in late summer 2003, assessment of the damage was undertaken between November and December 2003. The area below the Cruden Wall on the W side, and the southern edge of the hill from the SW corner along to the E end, have all been damaged. A walkover survey revealed significant new information about the ramparts and terraces of the site, since stonework was markedly more visible than normal because of the loss of soil and vegetation. Some previously un-noted terraces were identified, and revetment walls were revealed on many others. The defensive system appears more complex than has been noted before. A total of 44 test pits were excavated to assess the scale of damage, which varied considerably from superficial to severe (the soil converted to ash at depths of up to 0.4m). Fieldwalking of the burnt areas produced a scatter of finds, including samian and Roman glass.

Sponsors: HS, NMS.

F Hunter and A Dunwell 2003.

Excavation (2004)

NT 582 746 Following a devastating fire on Traprain Law in late summer 2003 and subsequent assessment work (DES 2003, 62) a series of remedial excavations was carried out on various parts of the hill. During spring and summer 2004 work focused on a damaged part of the S fringe of the summit area, with additional trenches excavated in burnt areas on the upper slopes on the S, E and W sides of the hill. The aim was to recover archaeological evidence from areas damaged and left vulnerable by the recent fire, and to provide additional information to aid the future management

of the site.

The main focus of the 2004 excavations on the S edge of the summit was the W half of the medieval building S of the pond, the E half having been dug in 1997 (PSAS 130, 413-40). From the earlier work it was known that the building was constructed partly of massive stone wall footings (along its S wall), and partly utilised bedrock (for its N and E walls), but partial excavation had not clarified the character of the occupation. Much additional information was recovered from the 2004 excavations. The massive foundation stones along the S side of the building had supported a turf superstructure, with individual turfs recognisable among the collapsed material. Two successive floor surfaces, incorporating paving and other internal features, were identified in the W half of the building, confirming that it had undergone a complex sequence of occupation. Interpretation in the building, and indeed across the site as a whole, was severely hindered by rabbit burrowing which has caused (and continues to cause) tremendous damage to the archaeological deposits on the Law.

Although there were numerous finds from the medieval building, most were clearly residual and added little to the 14th-century abandonment date suggested by pottery from the previous excavations. One intriguing find is a small stone fragment recovered from the turf wall core, which bears a series of distinctive linear carvings apparently from a rock art panel similar in style to those on the NE side of the hill which were destroyed during quarrying operations in the 1930s. The context of the fragment could be interpreted either as residual (in redeposited turf) or placed (as a wall foundation deposit).

Immediately N of the medieval building and just S of the pond, which forms one of the major visible features of the summit, an area of metalled flooring was identified. From the dense concentrations of cannel coal waste (mainly restricted to primary processing debris) above this surface, it has been interpreted as the remains of a specialised cannel coal working area of later prehistoric date. A further surface and wall underlay this but were not fully

excavated.

On the edge of the summit, just S of the medieval building, trenches were excavated over a terrace newly revealed by the fire. A series of stone wall footings and metalled surfaces associated with a hearth were identified; the walls did not survive well, but the structure(s) appeared to be sub-rectangular. Finds (including later prehistoric pottery, a stone ball and a whetstone) suggest a broadly Iron Age date. A flat area of outcropping bedrock, which had been used as part of a floor in the Iron Age, bore a series of earlier rock carvings. The motifs were dominated by pecked cupand- ring marks, with multiple rings and connecting radial grooves. However, there were also lozenge, chevron and other motifs of

unusual character. In form and condition, the cup-and-ring marks parallel those found on the NE of the hill (see above) but without the linear motifs which predominate in the latter area.

A second major focus of investigation was a trench just below the extreme E end of the summit area, where the fire had exposed stone features below an entrance through the late Roman period Cruden Wall. Excavation revealed a terraced construction forming a sloping path or ramp leading towards this entrance. Construction varied along the course of the ramp, with at least one area of resurfacing. The structure was exposed for a stretch of c 25m. Its projected lower course would have run through the area removed by quarrying on the NE side of the hill. The path seems both to permit and control access to the E entrance through the Cruden Wall. Associated finds were few, but include a fragment of a sheet bronze vessel.

The Cruden Wall was also examined where it terminated against the bedrock on the SW corner of the hill. Here the structure had been partly undermined by fire, exposing a construction similar to that seen in previous excavations, of substantial stone facing with a core of rubble and earth. The Cruden Wall here, however, was very poorly preserved and no deposits survived beneath it.

One further area of excavation was of particular note. On a small and precipitous ledge towards the top of the cliffs which fringe the S face of the Law, a hoard of four socketed and looped Late Bronze Age axeheads was found. These had been placed in a small shallow crack in the near-vertically sloping bedrock at the rear of the ledge. The sediments on the ledge had been burnt to a bright orange ash by the recent fire and any associated layers had been homogenised; the burning had also caused some damage to the bronzes themselves.

A series of other trenches were opened on terraces, principally on the W slopes of the hill. Most produced evidence for in situ archaeological deposits, and these terraces clearly formed the focus for human occupation at various points in the site's history. Finds include Roman pottery, Iron Age beads and bangles of glass, shale and cannel coal, and a small fragment of sheet gold.

Overall, the work in 2004 once again highlighted the importance of Traprain Law throughout prehistory and into the medieval period.

It has further shown how exposed and vulnerable the enormously rich archaeological deposits on the site remain to a range of threats, most importantly rabbit and fire.

Archive to be deposited in NMRS.

Sponsors: HS , NMS.

I Armit, S Badger, F Hunter, E Nelis 2005

Excavation (August 2005)

NT 580 747 Work in August 2005 concentrated on completing excavation of the western end of the medieval building first examined in 1996-7 and further investigated following a devastating fire in 2003 (DES 2003, 62). This modifies the results from 2004 (see above). The medieval building was shown to be a single-phase construction overlying earlier floor surfaces. No contemporary finds and few structural traces were recovered, and this end of the building may have been a store, with any occupation at the E end (where pottery was recovered in previous work).

Two phases of later prehistoric levelling deposits underlay the building, filling gaps in the bedrock to provide a level surface. The lack of structural evidence suggests this was an outdoor area rather than part of a structure.

Some 50m to the WSW, fire had exposed a further terrace on the steep southern slopes of the hill. Half of this was available for examination. In the time available it could only be stripped and mapped, but the well-preserved remains of a sub-rectangular building were revealed, with a doorway in the N side and a nearcentral hearth. It was 4.5m wide externally (2.4m internally), and if symmetrical would have been c 12m long. A sturdy wall built into an Iron Age midden provided the footings for a turf wall on the S side; elsewhere this was founded on bedrock or cobble foundations.

The date of the building is uncertain, as the occupation deposits had been homogenised or destroyed by the fire, although Late Roman pottery was found insecurely associated with the wall.

A further programme of fieldwalking and metal detecting over the burnt areas revealed a rich and diverse range of finds. Notable items include a conical gaming piece of cannel coal, beads of cannel coal and glass (including a Late Roman glass bead), a penannular brooch, a button-and-loop fastener and a range of Late Roman pottery. Earlier prehistoric finds include a microlithic core and a flake from a polished stone axe.

Archive to be deposited at RCAHMS.

Sponsors: HS , NMS.

F Hunter 2005

Publication Account (2005)

Two archaeological survey projects have recently been carried out on Traprain Law. In 1999-2001, the Traprain Law Summit Project (TLSP) sought to assess the nature and extent of human activity across the area within the inner rampart; this had seen little previous investigation and was felt to be threatened by rabbits and accidental fire. In late 2003, a fire burnt out huge swathes of the hill, leading to a programme of assessment and rescue excavation which involved the excavation of over 20 trenches (most of them small) and numerous test pits; this was carried out in 2003-4. The recent work has certainly added new layers of complexity to the biography of the Law. Many of the TLSP trenches were set out explicitly to test 'blank' areas of the summit and to give some picture of the nature and density of the archaeological deposits across a site which has a long and varied past.

Evidence for Neolithic and Bronze Age activity on Traprain suggests its use as a ritual focus and occasional burial place. The collection of rock art that was recorded during the 1930s has been augmented by the discovery of a new panel. The discovery of further polished stone axes demonstrates that Neolithic activity of uncertain character ranged more widely across the hill than previously thought, but there remains no evidence for substantial occupation during the Neolithic or early Bronze Age.

The picture changes markedly thereafter. Late Bronze Age metalwork from Curle and Cree's excavations had already indicated intense activity around 950-700 BC. However, radiocarbon dates from cereal grains found within occupation deposits in several of the recent trenches suggest a rather greater time depth to the Bronze Age occupation. Although most relate to the activity in the 10th or 9th centuries, others more probably reflect settlement in the later 2nd millennium BC.

Dating the rampart system has been a perennial problem, but radiocarbon dates were obtained for the innermost enclosure. The surface remains of this feature are no more than discontinuous scarps and rickles of stone, and it had been discounted as a rampart by some authorities. However, excavation revealed the remains of a terraced bank with a well-built outer stone face incorporating crudely-faced stonework. Three radiocarbon dates from below the rampart suggest that there activity on this part of the site in the late 2nd or early 1st millennia BC. A further date, from material formed against the rampart, is virtually indistinguishable, suggesting that the rampart was built before 1010-790 cal BC. Taken at face value, this suggests that the summit enclosure was constructed during the Late Bronze Age, although it is clearly desirable to obtain more dates for these deposits. We also obtained LBA dates from under the inner rampart, but these provide only a terminus post quem. The fire has revealed numerous outworks on the W side of the hill, as well as a previously-recorded rampart on the S side. These features are undated, but would have made the rampart systems considerably more impressive.

In 2004, a hoard of four socketed and looped axe-heads was found buried on a ledge on top of the cliff that fringe the S side of the hill. The precipitous location of their discovery suggests a votive purpose, although the hill was still a thriving settlement. The lack of distinctive pre-Roman Iron Age material from early excavations has long been seen as problematic, but the material culture of the Scottish Iron Age is notoriously impoverished and undiagnostic, so this apparent absence need not be fatal to the traditional interpretation of Traprain as a pre-Roman tribal centre. However, the radiocarbon dates from the recent work relate exclusively from the Bronze Age, despite attempts to date grain from all viable stratified contexts. It is difficult to escape the impression that pre-Roman Iron Age occupation was far more restricted than that of earlier and later periods.

Nevertheless, there are some likely candidates for Iron Age buildings, particularly from the 2004 rescue work for which radiocarbon dates have yet to be obtained. In particular, there is an artificially enhanced terrace on the S edge of the summit, just above the cliffs that form a natural barrier on this side of the hill. A series of stone wall-footings and metalled floors were found associated with later prehistoric pottery and a stone ball of probable Iron Age date. One of these structures contained a well-built hearth and utilised a flat area of outcropping bedrock as part of its floor. On this floor, there were several rock-carvings of much earlier date, some of which would have been exposed in the floor of the later building. In a nearby trench (slightly closer to the summit), there was a metalled surface, which was apparently used as a cannel coal working area; this was also probably of later prehistoric date.

Set between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall, the location of Traprain placed it variously inside and outside the Roman Empire during the first few centuries AD, making the site pivotal to any understanding of Roman-native relations during this period. Despite some suggestions that Traprain may have been essentially a ritual centre during the Roman period, with only a very limited resident population, the recent work has tended to support the more traditional view of the site as a Roman 'boomtown'. For example, excavation of a steeply-sloping area of the inner rampart revealed that its collapsed remains were sealed by a deep accumulation of floor deposits, the uppermost associated with Samian pottery of the 2nd century AD. The use of such inconvenient, steeply sloping corners of the hill for the construction of buildings suggests that space may have been at a premium. Indeed, one of the recurrent features of the present work has been the density with which Roman Iron Age activity is distributed across the hill. On the basis of our assessment trenches, many of the artificially enhanced, slab-fronted terraces on the slopes below the summit seem likely to date to this period.

The recent work has also added to our understanding of the last defensive work on the site, the late Roman Iron Age 'Cruden Wall'. Where the recent fire had exposed stonework on the E side of the hill, we were able to excavate a carefully-built stretch of terraced road or path which both facilitated and controlled access to one of the gates on the 'Cruden Wall', making the entrance a dramatic one.

New information has also emerged regarding the medieval re-use of the hill. Gerhard Bersu's excavations in the 1940's had hinted at a 13th or 14th century AD for a rectangular enclosure around the highest point on the summit. The recent work bears this out, but has also what appears to be a child's long cist burial within the enclosure, suggesting the presence of an early medieval burial-ground. Rectangular foundations discernible below the modern hiker's cairn on the summit itself may even represent the remains of an accompanying chapel. A substantial stone-footed turf-built building on the S edge of the summit area has also been dated to the 13th or 14th century, and could represent an ancillary building dating to an ecclesiastical focus on the hilltop. One possible context for these concerns a set of traditions relating Traprain Law to the life of St Kentigern, patron saint of Glasgow. Traprain lay close to the well-trodden pilgrimage routes of eastern Scotland, and the popularity of St Kentigern during the 13th and 14th centuries may have sparked renewed interest in the site.

[Illustrations include plan of Traprain Law showing main areas of excavation and locations of recent discoveries of rock art and axes, also colour photograph of the axe hoard].

Sponsors (both projects): Historic Scotland, National Museums of Scotland.

Additional sponsors (TLSP): Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Russell Trust, Society of Antiquaries of London, University of Edinburgh Munro Lectureship Trust.

I Armit, A Dunwell, F Hunter and E Nelis 2005.

Excavation (June 2006)

NT 580 747 The final stage of rescue work after the 2003 fire took place in June 2006 (for earlier work see DES 2005, 55-6).

Work focused on two areas:

- the completion of area P, a small rectangular building on the southern edge of the summit, some 50m WSW of the medieval building investigated in 2004-5

- area Q, one of the terraces to the SW of the inner rampart, above the end of the Cruden Wall

The area P building proved to be a single-phase structure terraced into an earlier midden. Surface indications suggest around half of it was exposed, giving overall dimensions of some 12 x 4.5m, with a door in the centre of the N side and a central hearth. Other internal features were a possible post-pad near the W end and a small pit. There was a laid cobble floor, but no occupation deposits survived. However, a terminus post quem was provided by a late Roman glass bead in the wall core. Under the southern wall was a cache of 75 cattle and horse teeth, mostly molars, which is likely to be a votive foundation deposit.

The building had been terraced into an earlier midden which produced large quantities of pottery and bone, and (in contrast to much of the site) had seen little rabbit disturbance. Initial indications from mould fragments are that this is likely to be Late Bronze Age in date. In the area where the N wall of the building later lay, a pit was cut into the top of the midden and lined with stones.

Area Q appeared on the surface as a terrace defined by a tumbled line of stones. Excavation revealed most of a sub-rectangular building with a cobbled surface upslope which was probably a yard. A hearth was set into this. The building had turf walls on stone foundations; those on the downslope side had slumped, but the others were readily traced. Rabbit activity had caused considerable damage, but an internal floor surface and hearth were located. The centre of the building had a levelled cobbled surface; at the ends the surface was more uneven, with cobbled patches among exposed bedrock. No occupation deposits survived and the date is uncertain, although the building's morphology is similar to others from the latest phases on the hill. Within the collapsed remains of the building, a later hearth was built, apparently representing a temporary reoccupation. Finds from hillwash included a complete lower stone of a rotary quern, late Roman pottery and a late Roman glass bead.

Both trenches suggest that in the late phases of the site, around the late Roman period, there was pressure on space, with buildings being constructed in areas previously avoided or used for rubbish disposal.

Archive to be deposited with the NMRS; finds in NMS.

Sponsor: National Museums of Scotland

Fraser Hunter, 2006.

Note (8 January 2016 - 3 April 2017)

The craggy outline of Traprain Law, which is a distinctive landmark along the Lothian Plain, has been tailored to a series of fortifications that rank amongst the largest in Scotland, at its maximum extent enclosing an area of about 16ha. While noted in 1792 by the minister of the parish of Whittingehame, who recorded what was probably the rampart known as the Cruden Wall and speculated that it had been constructed as a place of safety against the Danes or the English (Stat Acct, ii, 1792, 349-50), the antiquarian record is curiously mute, and the fort is not annotated on any county maps, nor the first two editions of the OS 6-inch map. making its first appearance with a perceptive depiction of the ramparts on the revised edition of the first OS 25-inch map (Haddingtonshire 1907, sheet 11.1). This depiction evidently formed the base for Alexander Curle's first plan (1915, 141, fig 1), produced at the outset of the campaign of excavations 1914-15 and 1919-23, and the plan subsequently published with the addition of contours, and a summary probably written by Curle, in the County Inventory for East Lothian (RCAHMS 1924, 94-9, no.148, fig 137). The extent of these excavations and subsequent interventions in 1939 by Stuart Cruden (1940), and 1947 by Gerhard Bersu (Close-Brooks 1983), were depicted on a plan drawn up in 1955 by two teams from RCAHMS and published by Richard Feachem (1956, opp 286, fig 2), and it is this plan that has formed the basis for all subsequent discussion of the defensive sequence (Hogg 1975, 95-9; Jobey 1976; Close-Brooks 1983, 207-9). In essence Feachem postulated a series of four perimeters, expanding from what is now confirmed in the most recent campaign of work (Armit, Dunwell and Hunter 1999) to be the remains of a rampart enclosing about 10 acres on the summit. Apparently, open along the cliff-edge that forms the SE flank of the hill, the line of this rampart can be traced along the SW lip of the summit area before returning across the slope on the NW for a distance of up to 300m, where it variously forms a low stony scarp or a line of boulders, the latter apparently outlining an entrance facing out NNW towards North Berwick Law, though the alignment on this other East Lothian landmark is not as precise as some would wish to believe. The lip of the summit area is also adopted by what is probably an 8ha enclosure, following the natural crest-line down across the slope on the NW before turning back along the northern flank where it can be followed as an intermittent terrace back to the edge of the quarry that scars the NE tip of the hill. This rampart was exposed in three trenches by Cruden (1940), along with a lower rampart reduced to a terrace that descends the slope westwards. The possible junction between these two ramparts that lies a little further ENE and has not been excavated, but Feachem proposed that this was part of a later 12ha enclosure that had been subsumed on the W into the massive rampart that forms a bold terrace extending along the NW flank of the hill and swinging southwards along a pronounced lip on the SW face of the hill to enclose an area of about 16ha. Joanna Close-Brooks expressed some doubt as to the existence of this 12ha enclosure (1983, 209), though its slightness is perhaps accounted for in the robbing that must have taken place to build subsequent ramparts, and whether it is really embedded in the line of the largest enclosure, or perhaps cuts across the slope along a terrace intersected by a trackway mounting the slope on the NW, can only be demonstrated by further excavation. What is certain, however, is that a stone wall, the Cruden Wall, built along the line of the massive terrace rampart of the 16ha enclosure on the SW, mounts the slope on the NW, not only crossing the line of the supposed 12ha enclosure here, but also that of the 8ha enclosure, this latter stratigraphic relationship demonstrated by Cruden (1940); this wall takes in about 12ha and was extensively examined by Cruden above the quarry on the NE, not far from where the wall turned back onto the cliff-edge on the S and was pierced by an entrance. Elsewhere, the Cruden Wall exploits three earlier entrances through the terrace rampart on the WNW and W, albeit that the passage through the southern of the two gaps on the W appears to have been narrowed, while a fourth entrance through the terrace rampart lies on the N adjacent to the quarry. These entrances have witnessed heavy traffic and are approached on the NW and W by heavily worn trackways. Within the interior one trackway climbs obliquely up the slope from the narrowed entrance to a natural cleft in the lip of the summit area near the cliff-edge on the S, which is likely to have been an entrance into both the 4ha and 8ha enclosures, while a second track mounts the slope from the NW entrance, firstly to reach the plateau area where Curle and James Cree dug extensively, and then obliquely NE to a gap in the rampart on the NW of the 8ha enclosure, its course picked up by a line of stones flanking its NW side and leading towards a string of three or four rectangular buildings. Elsewhere, on the slope forming SW flank of the interior, Feachem recorded numerous small elongated platforms that appear better suited to rectangular structures than circular ones. The excavations by Curle and Cree encountered deep stratified deposits on the plateau area halfway up this slope, recovering numerous hearths and fragments of both circular and rectangular structures, though the record of their discoveries is too all intents and purposes irrecoverable. The area had certainly been intensively occupied during the Roman Iron Age, providing a wealth of Roman goods that far outstrips any other site in Scotland and, unusually, seems to have prospered from the 1st century AD through at least the 3rd and 4th centuries into the 5th century. Mainly excavated in spits, from the lower levels they also recovered a large assemblage of Late Bronze Age metalwork. While these finds suggest two principal horizons of occupation on the hill, the dating of the ramparts is imperfect, though single entity radiocarbon dates from contexts below the rampart of the 4ha enclosure on the summit fall in the Late Bronze Age, and an indistinguishable date was returned from an ashy deposit that accrued against its inner face (Armit, Dunwell, Hunter and Nelis 2005). Otherwise the Roman finds from the terrace bank, clearly place this in the early centuries AD, though Close-Brooks has queried whether these items relate to material that has accrued behind an earlier, perhaps pre-Roman, rampart a little further down the slope, rather than from the rampart core itself; this possibility becomes stronger in the light of the unpublished radiocarbon dates returned more recently from samples recovered in 1986 by Peter Strong from the outer defences adjacent to the quarry on the NE. Nevertheless, 3rd and 4th century finds recovered by Bersu and Cruden clearly provide a terminus post quem for the Cruden Wall, while Close-Brooks also suggests that a pin excavated by Cruden from an earlier structure above the quarry might place its construction in the 5th century AD. However, in the light of an excavation carried out in 1986 at the foot of the hill on the NE, which found that two palisade trenches had been replaced by a bank and ditch and finally superseded by an earthen rampart with an external stone revetment (Strong 1986), it would be naive to suggest that the plan of the visible elements of the defences can be understood with a simple model of expansion or contraction, and that the narrow trenches excavated to date provide any real insight into their construction or chronology. Whether the Late Bronze Age activity attested by the finds on the western end of the hill fell within a Late Bronze Age enclosure, has yet to be demonstrated.

Information from An Atlas of Hillforts of Great Britain and Ireland – 03 April 2017. Atlas of Hillforts SC3932

Note (April 2017)

Traprain Law fort and settlement, East Lothian

Summarising the story of an excavation or a site can be one of the most difficult things for an archaeologist. To who should it be addressed? What is the vital information? Where should the emphasis be laid? Each of us writes for our audience, and we all try to balance between information and hyperbole. Many archaeological sites read as a palimpsest (1) but the representation of that story in writing and illustration, or archaeological records like Canmore, presents a significant challenge.

This challenge is brought into focus at Traprain Law, a volcanic hill set among rich East Lothian farmland. While deceptively simple at first glance, the archaeology of Traprain is made especially complex by both its sheer size and the richness of the archaeological finds (about 5% of the site has been excavated over the years). Numerous objects from the Late Bronze Age period through to the late Roman period in particular have been recovered, representing burial, settlement, agriculture and trade over 1,500 years. One of the most exciting came in 1919 when workmen uncovered a pit containing 34kg of Roman silver, but remarkable discoveries have continued: a small hoard of Late Bronze Age axe-heads came to light in 2004. Activity continued in later years and there is a growing argument for medieval occupation and burial on the summit, a reminder of the link to St Kentigern - recorded in the 12th century - and the existence of a 16th century beacon. Two hundred years later plantations of trees were established on the summit, and in the late 19th and 20th centuries the NE of Traprain was the site of the one of the county’s largest quarries.

[(1) a manuscript written over a partly erased older manuscript in such a way that the old words can be read beneath the new]

Classification and survey

For archaeologists of the 1950s and 1960s, Traprain was considered as a prehistoric fort since it is enclosed by a large defensive ramparts. Creating their records in 1962, the Ordnance Survey recognised the fort and some 26 categories of find, from spindle whorl to arrowhead. Separate cards recorded each element, listing the relevant references, and a thorough critical summary was provided. The term fort, while satisfactory in some contexts, here disguises the complexity of the site and its long history of settlement. The difficulties of organising information are compounded when one considers the archive material – some 700 items survive including plate photographs, manuscripts, and drawings, many of which offer subtle clues or critical enhancements in understanding. The finds, most of which are housed in our National Museum, present another rich seam for study, and recent re-analysis has offered new perspectives.

While the organisation and structure of archaeological information clearly presents a challenge, the survey of the Traprain has also caused significant difficulties. Despite the fact that the Law was at the centre of the county Ordnance Survey in 1851, even the largest ramparts of the fort escaped record until 1906 (though a detailed survey of nearby Chesters fort was prepared in 1851). Early excavators provided only a schematic plan, and the RCAHMS Inventory of 1924 relied on the 6-inch map. The task of preparing a large-scale plan fell to RCAHMS in 1955, led by their archaeologist Richard W Feachem. Due to the size of the hill and the steepness of the slopes, Traprain presented a particular challenge requiring some 120 survey stations. The inked plan, still regularly reproduced, was crucial in demonstrating the existence of at least four different forts, not the one or two previously supposed. One mistake took 25 years to correct – because of differences in the orientation to magnetic or grid north, some trenches were drawn at the wrong angle!

During this summer HES Survey and Recording are preparing a new survey of Traprain and will face many of the same challenges. The survey will be split into three parts – collection of data, archaeological interpretation, followed by depiction and dissemination. We are now spoiled by the ability to call on centimetre accurate GPS equipment which will, but for the most awkward area among steep cliffs, provide an accurate spatial fix. To this we can add a 3D model developed from hi-resolution aerial photographs and, using visualisation software, this will allow the enhancement of specific slopes in order to help us ‘read’ elements the landscape. Interpretation has come on in other ways since 1955 and the experience of RCAHMS in the Borders, Perthshire, Aberdeenshire and Dumfriesshire in particular has helped the surveyors see more clearly than two generations ago, and to pick up nuance and subtlety which in 1955 may have simply been generalised out. Depiction though is a fast developing art. Where careful use of ink pen and hachure was the mode then, depiction now relies on skills with software and the application of field interpretation in 3D represents a significant (but potentially rewarding) challenge. Clarifying the natural hill from the archaeological features, exposing the character of stratigraphic relationships, and piecing together a coherent narrative are still the order of the day.

While Traprain retains a particular significance in Scotland, the wider archaeological picture has dramatically changed since the first excavations in 1914. Where the 1924 Inventory recorded some 264 sites in East Lothian dated earlier than 1707, the current record in Canmore number some 3404 archaeological sites. The discovery of cropmark sites in the fields surrounding the Law has completely changed our notion of Traprain as an isolated capital, while programmes of excavation such as the Traprain Law Environs Project and the archaeology of the A1 road have transformed the regional picture. That said, the Law still presents an extraordinary picture of prehistoric and historic activity and is a special place whose resonance will continue through the ages. Why not take a walk up it the next time you are out there and see how many ramparts you can find!

References

Curle 1914; RCAHMS 1924; Feachem 1958; Rees and Hunter 2000; Armit, Dunwell, Hunter and Nelis 2005

George F Geddes - Archaeology Project Manager

Field Visit (May 2018)

Traprain Law Fort

Traprain Law rises to a height of 221m OD above the farmland of East Lothian, the highest point in a broad swathe of land between the River Tyne to the N and the Whittinghame Water to the S. Roughly triangular on plan it is bound by steep ground to the NE, NW and SE, the latter forming broken cliffs that prevent ready access. At the SW the ground descends more gently while the interior is divided into a large relatively level summit plateau, and smaller terraces to the W and N. The NE end of the hill has been severely diminished by quarrying that removed about 10% of the surface area of the hill before operations ceased in 1975.

Traprain bears the traces of one of the largest prehistoric forts in Scotland, the internal area measuring over 16ha at its maximum extent. Despite a brief reference in the Statistical Account (ii, 1792, 349-50), the fort received little notice in the 19th century (but see Maclagan 1875) and was first delineated in 1907 (OS Haddingtonshire 1907, sheet 11.1), benefiting from a detailed account by Alexander Curle a few years later (1915). Excavations by the Society of Antiquaries under Curle and James Cree between 1914 and 1923 focussed on the western terrace, with a series of smaller cuttings elsewhere, amounting to about 5% of the internal surface area. Statutory protection followed, and a summary and plan were published a year later (RCAHMS 1924, 94-9, no.148, fig. 137).

The continuation of quarrying caused enough concern for three smaller excavations to be undertaken: by Stewart Cruden in 1939; Gerhard Bersu in 1947; and Peter Strong in 1983 (Cruden 1940; Close-Brooks 1983; HES Archive: WP005495). Widespread fire damage prompted new phases of rescue excavation in 1996-7 and 2003-4, which have bolstered the unpublished results of the Traprain Law Summit Project (2000-1), each suggesting that the relatively smooth surface of the fort’s interior belies the widespread preservation of stratified deposits and structures (Rees and Hunter 2000; Armit, Dunwell, Hunter and Nelis 2005; MS2673).

RCAHMS made the first detailed archaeological survey of Traprain in April 1955 and the published plan and accompanying description by their archaeologist Richard Feachem (1958) has formed the basis of subsequent discussions of the visible remains and the defensive sequence (e.g Hogg 1975, 95-9; Jobey 1976; Close-Brooks 1983, 207-9). Feachem’s tentative division of the site into at least four principal phases relied in part on the excavations by Cruden (1940). To facilitate comparison the nomenclature used by Cruden and Feachem has been included in this description where relevant, while the principal elements of the fort’s defences have been separated into four phases, with shorter descriptions dedicated to the putative outworks and the interior. The description is designed to be read in conjunction with the overall plan of Traprain Law, and with the simplified version thereof. For further information on other elements of the site, including the quarries, field systems and medieval settlements, the reader is directed to the appropriate Canmore entry.

Fort I (10 acre)

The traces of a rampart, reduced to a grass-grown stone bank (I), enclose about 10 acres of the summit plateau (OS Haddingtonshire Sheet XL.1, 1907; Curle 1915, fig. 1; Hogg 1951, fig. 54; Feachem 1958, 286). The rampart is best preserved about 60m NE of the summit where it runs for about 50m from ENE to WSW measuring about 3m in thickness and 2m high with occasional larger boulders perhaps representing a revetment. The line of the rampart is lost further to the ENE but it can be tentatively traced running to the WSW as a fragmentary scarp before turning S to follow a natural crest line. Some 200m to the WSW of the summit there is another well-preserved section some 30m long, spread up to 5m in thickness and about 1m in external height. The original entrance into this fort is not clear, although a natural cleft at its SW corner probably provides the best candidate. Another entrance, some 100m WNW of the summit is lined by earth-fast boulders but both its character and location is unusual for a prehistoric fort and it may relate to the later, medieval, occupation of the hill. The house platforms shown on the RCAHMS plan, one of which was noted by George Jobey (1976, 195), have been discounted but one possible house platform 97m NE of the summit has been identified. Two small trenches (4 and 6 on the plan) were excavated across the rampart of the 10-acre fort in 1999 under the direction of Ian Armit, Andy Dunwell and Fraser Hunter (MS726/177). The excavators have tentatively suggested that it may have been constructed in the Late Bronze Age (Armit el al 2005, 3).