Scheduled Maintenance

Please be advised that this website will undergo scheduled maintenance on the following dates: •

Tuesday 3rd December 11:00-15:00

During these times, some services may be temporarily unavailable. We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause.

Bonawe Ironworks

Iron Works (18th Century)

Site Name Bonawe Ironworks

Classification Iron Works (18th Century)

Alternative Name(s) Bonawe Furnace; Lorn Furnace; Taynuilt; Brochroy

Canmore ID 23521

Site Number NN03SW 5

NGR NN 00974 31882

NGR Description Centred NN 00974 31882

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/23521

First 100 images shown. See the Collections panel (below) for a link to all digital images.

- Council Argyll And Bute

- Parish Glenorchy And Inishail (Argyll And Bute)

- Former Region Strathclyde

- Former District Argyll And Bute

- Former County Argyll

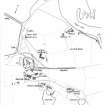

NN03SW 5.00 centred 00974 31882

(Area centred NN 010 318) Lorn Furnace (NAT)

(NN 0125 3170) Bonawe House (NAT) (See NN03SW 5.01)

OS 6" map, Argyllshire, 2nd ed., (1900)

NN03SW 5.01 NN 01255 31801 Bonawe House

NN03SW 5.02 NN 00985 31874 Lorn Furnace (Lorne Furnace)

NN03SW 5.03 NN 01010 31846 ore-shed

NN03SW 5.04 NN 01004 31814 E charcoal-shed

NN03SW 5.05 NN 00967 31819 W charcoal-shed

NN03SW 5.06 NN 01007 31964 Shore House / NE workers' dwellings

NN03SW 5.07 NN 01075 31790 1-4 Lochandhu Cottages / SE workers' dwellings

NN03SW 5.08 NN 01513 32021 aqueduct

NN03SW 5.09 NN 01057 31956 domestic outbuildings

NN03SW 5.10 NN 0150 3074 cultivation remains

For (associated) Bonawe Jetty or Pier (NN 0075 3217), see NN03SW 16.

For associated weir across River Awe (at NN 01643 32049), see NN03SW 45.

NMRS REFERENCE:

Scottish Field October 1966 p. 42 - article and photographs

(Undated) information in NMRS.

As described.

Surveyed at 1:2500.

Visited by OS (GHP) 18 April 1962 and (RD) 21 October 1971

The Lorn iron furnace at Bonawe, near Taynuilt, is an important example of early industrial activity in Scotland. It was established by the Newland Company (later known as the Lorn Furnace Company) in 1753 with the object of using locally produced charcoal to smelt haematite ore brought from Lancashire and Cumberland. As well as constructing a furnace and workers' dwellings, the company erected numerous ancillary buildings including a school, a church, and a quay, thus creating a small industrial community which soon became an object of some curiosity to travellers in the Highlands. The furnace was finally closed down in 1874 and the buildings thereafter abandoned or put to other uses and generally the small complex was in danger of obliteration by neglect.

An extensive programme of repair and consolidation is currently being undertaken by DoE.

The furnace buildings occupy a focal position on the site, standing a little to the north of the coal-house and ore shed, and immediately beside the principal access road from the quay. The blast furnace itself survives more or less intact together with the ruins of other ancillary buildings and structures.

Nearby Bonawe House was built as a residence for the manager of the company and is situated in wooded grounds 300 metres ESE of the main group of furnace buildings (see NN03SW 5.1).

(A detailed description of the furnace and the various buildings on the site is given).

A Fell 1908; RCAHMS 1975, visited 1971.

(Location cited as NN 093 318). Founded 1752 by Richard and William Ford, James Backhouse and Michael Knot; the most important monument of the early Scottish iron industry.

The furnace is square in plan, rubble-built, with a brick stack; the lower part of the lining is missing. The lintels above the tuyeres arch and tap hole are cast iron, one bearing the inscription 'Bunaw F 1753'. Attached to the furnace are the bridgehouse and fragments of the walls of the blowing-engine house and the casting house.

Behind the furnace are three sheds; the larger two were charcoal sheds and the the third, which has partitions internally, was an ore shed. Adjuncts include two ranges of workers' housing (one of them on an L-plan), and a rubble pier (on a T-plan).

Now a Guardianship Monument, beautifully restored by the Department of the Environment.

J R Hume 1977.

Bonawe (Lorne Furnace). Complete ironworks complex, with furnace ('BUNAW.F.1753' - on lintel), without lining, filling house, ruins of casting house, two charcoal sheds and one shed. Also fine L-shaped row of worker's housing (2 storey). All stone built, slate roofed, houses whitewashed.

Visited and photographed by J R Hume, University of Strathclyde, 1977.

NMRS, MS/749/77/1.

Publication Account (1753 - 1757)

The furnace was built for Cumbrian ironmaster Richard Ford, who founded the Newland Company of Furness. The iron lintels over the tap holes are dated 1753 and 1757.

The works were in almost continuous production for 120 years until they closed in 1876.

R Paxton and Jim Shipway 2007b

Reproduced from 'Civil Engineering heritage: Scotland - Highlands and Islands' with kind permission from Thomas Telford Publishers.

Photographic Survey (1960)

Measured Survey (1962 - 1973)

A series of measured surveys were undertaken by RCAHMS at Lorn Furnace, Bonawe, between 1962 and 1973. In each case, an original pencil drawing was redrawn in ink and the resulting illustration was published at a reduced scale. The final set of illustrations published in 1975 (RCAHMS 1975, figs 236-247) included:

Fig. 236: Site-plan

Fig. 237: General plan of furnace

Fig. 238: Upper plan of furnace

Fig. 239: Elevation and section of furnace

Fig. 240: Elevation of E charcoal shed

Fig. 241: Plan and section of furnace, ore-shed and charcoal-sheds

Fig. 242: Roof-details and section of E charcoal-shed

Fig. 243: Roof-details and section of W charcoal-sheds

Fig. 244: Ground and first floor plans of NE workers' dwellings

Fig. 245: Ground and first floor plans of SE workers' dwellings

Fig. 246: Elevation of SE worker's dwellings

Fig. 247: Ground and first floor plans of Bonawe House

Photographic Survey (June 1964)

Photographic survey of Bonawe furnace and ironworks, Argyll, by the Scottish National Buildings Record in 1964

Photographic Survey (March 1965 - 31 March 1965)

Photographic survey by the Ministry of Works in March 1965.

Measured Survey (July 1966 - November 1969)

Field Visit (14 May 1976)

(Location cited as NN 093 318). Founded 1752 by Richard and William Ford, James Backhouse and Michael Knot; the most important monument of the early Scottish iron industry.

The furnace is square in plan, rubble-built, with a brick stack; the lower part of the lining is missing. The lintels above the tuyeres arch and tap hole are cast iron, one bearing the inscription 'Bunaw F 1753'. Attached to the furnace are the bridgehouse and fragments of the walls of the blowing-engine house and the casting house.

Behind the furnace are three sheds; the larger two were charcoal sheds and the the third, which has partitions internally, was an ore shed. Adjuncts include two ranges of workers' housing (one of them on an L-plan), and a rubble pier (on a T-plan).

Now a Guardianship Monument, beautifully restored by the Department of the Environment.

J R Hume 1977.

Field Visit (1978)

Bonawe (Lorne Furnace). Complete ironworks complex, with furnace ('BUNAW.F.1753' - on lintel), without lining, filling house, ruins of casting house, two charcoal sheds and one shed. Also fine L-shaped row of worker's housing (2 storey). All stone built, slate roofed, houses whitewashed.

Visited and photographed by J R Hume, University of Strathclyde, 1977. Information from NMRS MS/749/77/1.

Excavation (1978)

Publication Account (1985)

At a time when transport costs are perhaps one of the most contentious issues in the Highlands it is ironic that in the middle of the 18th century it was more economical to ship haematite ore from Cumbria to Loch Etive side for smelting and then to transport the iron back to the industrial centres around the Irish Sea, than it was to transport the enormous quantities of charcoal necessary to the Lake District The key was the cheapness and availability of timber for charcoal and a visit to the furnace at Bonawe should be coupled with a walk through the National Nature Reserve at Glen Nant to the south, where the types of timber and the platforms on which the charcoal was produced can still be seen.

The furnace complex embodies a building style quite unlike the architecture of the west of Scotland, betraying the Lake District origins of the company that established it in 1753. The centre of operations was the furnace itself but to appreciate the flow of operations the tour should begin on the uppermost terrace where the iron-ore shed and charcoal sheds are situated. The charcoal sheds are built into the natural slope to allow loading from a higher level behind and unloading from a lower level at the front where there is access to the furnace. The sheds are high and airy (to keep the charcoal dry) with impressive timber and slate roofs. The iron-ore shed is of two periods of construction: the three storage bays to the south-east belong to the earlier period, and the extension to the north-east is rather later. Again the ore was unloaded from the track at the rear of the shed and then barrowed from the front doors to the furnace itself.

The furnace is situated in such a way as to allow the constituents of the smelting process to be inserted into the loading-mouth from one level, while the water-wheel and lade, which powered the bellows at the base of the furnace-stack were on a lower terrace. The charcoal burning with the aid of the bellows (or latterly a blowing-engine) at the base of the stack, was covered with iron ore and limestone tipped in from the top; the heat changed the iron ore into molten iron, while the limestone flux above absorbed impurities and could be run off as molten slag. Both metal and slag were run off through the western of the great openings at the base of the furnace into a casting house where the metal was cast into pig-iron and the slag removed to form huge heaps (in the area now occupied by the car park). The two openings at the base of the furnace stack are lintelled partly in sandstone and partly by cast-iron beams, three of which have the inscription 'BUNAW. F. [Bonawe Furnace] 1753'; it seems likely that the lintels were cast in the Lake District in readiness for the building of the furnace, and the sandstone lintels were probably also brought from Cumbria in order to ensure the smooth construction of this crucial building.

To the north of the main complex is the L-shaped block that formed the workers' dwellings, and to the east is a further row of workers' dwellings and Bonawe House, built in the later 18th century as the residence of the company's local managec but none of these buildings is in the care of the Secretary of State for Scotland, and there is no public access.

Charcoal-burning stances are a little-visited class of monument found on many of the formerly wooded slopes of Argyll. The platformsl measuring about 8m in diameter, were partly dug back into the hill-side and partly built up on the down slope with the material thus quarried. On this level base logs were carefully stacked round a central stake and the pile was covered with earth; the stake was then removed and the pile set alight. The transformation of wood to charcoal took up to ten days. There are good charcoal-burning stances in Glen Nant (parking at NN 019273), and spectacular though less accessible platforms are to be found at the head of Glen Etive, above the west shore of Loch Etivei these have been cut back into the slope with the down-hill side revetted by large boulders. There are about twenty platforms on this now bare hill-side, a telling reminder that the slopes were once heavily wooded (NN 1044).

Another furnace went into production at Furnace on Loch Fyne side (NN 025000) by agreement between the Duke of Argyll and a Lake District company; the furnace stack can still be viewed from the outside. One of the lintels above the bellows opening is cast, like those at Bonawe, with the name, or in this case initials, of the operating company and the date: 'GF 1755' (Goatfield Furnace).

Information from ‘Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: Argyll and the Western Isles’, (1985).

Publication Account (1986)

Bonawe Ironworks, situated close to the s shore of Loch Etive by Taynuilt village, is one of the most extensive and best-preserved relics of the early iron industry in Britain. It was established in 1752-3 by Richard Ford and company as an offshoot of their works in Furness, and leases of the site and wood rights were agreed with the above-mentioned Sir Duncan Campbell and the 3rd Earl of Breadalbane for a period of 110 years. Haematite ore was brought in by sea from Lancashire and Cumberland, and a rotational system of coppicing was developed for the manufacture of charcoal, charcoal-burning stances being found in many of the natural woodlands around this part of Argyll. After expiry of the original lease in 1863, a new agreement was negotiated with Alexander Kelly of Bonawe, but the furnace finally closed in 1874.

As well as the furnace and storage sheds, the company erected a manager's house, workers' dwellings, and numerous ancillary buildings, which included a school, a church, a jetty and a truck-store, creating in effect a self-contained industrial community.

At the heart of the complex are the manufactory buildings, all of which occupy bankside positions on the sloping site, thus utilising the changes in level to assist what was essentially a gravity-feed process. They are solidly built of lime-mortared random or coursed rubble masonry, chiefly of the local granite, but numerous features betray their Lake District origins.

The charcoal sheds, or coal-houses, are spacious, well ventilated barn-like structures covered with open timber roofs of tie-beam construction arried down over the side-ranges as catslides. Loading-doors were situated in the rear walls, and unloading-doors, at the lower ground-level, at the front, whence the charcoal was barrowed or carried to the charging-house. The iron-ore shed, lying along the contours just NE of the charcoal sheds, was designed to be filled and emptied in a similar manner once the shipments of iron-ore had been carted up the hill from the jetty.

The blast-furnace is typical of the kind used during the later charcoal phase of the industry in Britain. The furnace openings have cast-iron lintels inscribed Bunaw. F. 1753. Apart from considerations of stability, the size and shape of the furnace were determined by the need for an adequate insulating core to reduce heat-loss and by the shaft within, whose design had to ensure a good draught and likewise prevent the friable charcoal from being crushed by an overweight of iron-ore.

The blowing-house, casting-house, store and smithy enclosing the furnace on its N and W sides are now ruinous, but the pitched roofs formerly covering these important ancillary structures can be traced by the socket-holes in the furnace walls for the roof-timbers-roofs, incidentally, which would have given an entirely different outward appearance to the furnace compared with today. Excavations have revealed the granite base-blocks of a blowing engine introduced at some time in the 19th century to replace the original leather bellows. Both types were powered through a camshaft worked by a low breast-shot water-wheel mounted in a pit and wheel-house along the E side. The floor of the casting-house was found to be divided by a stone kerb into a part-metalled area to the N and a bed of fine sand to the S.

The rear S wall is insulated from the earth bank and retaining wall by a narrow V-shaped cavity, which has a stone conduit running along its base and that of the casting-house-presumably for collecting seepage. At the upper level, the charging house and furnace were connected across the cavity by means of a joisted timber bridge (hence the alternative name bridgehouse), and by relieving arches on the side-wall. Directly beneath the bridge a long narrow chamber, carried on a joisted floor, was contrived within the cavity. Approached from the E by an external ramp, it probably served as a bothy for the furnace-keeper during the smelting operations, and possessed the amenity of a window and a fireplace set in the retaining wall, with horizontal flues issuing from the side-walls.

The principal manufactory buildings have been described approximately in the sequence in which they occur in the smelting process. Prior to this, the three ingredients-ironore, charcoal and limestone-underwent certain pre-treatment. Thus, the ore was washed, roasted and crushed to reduce its sulphur content and other impurities. The limestone was also broken down, and adequate stocks of charcoal had to be prepared, customarily supplied to the warehouses in 1 1/2 cwt. (76kg) bags and stacked there in dozens. It was also normal practice to pre-heat or season the furnace about a week in advance; the hearth area had to be relined where necessary and the apertures forming the tuyere and the tap-hole then sealed.

At the commencement of the smelting-operations the raw materials were assembled in the charging-house and measured in the correct proportions-the ore and limestone by weight, and the charcoal by volume-after which they were carried over the bridge and fed into the furnace shaft to its full height. Once the furnace was put into blast, the campaign (to use the trade term) was continuous, with recharging taking place constantly over a period lasting from about late autumn until early summer. Aided by a limestone flux for removing non-metallic impurities, the charge was heated and reduced to molten metal as it moved down the structure towards the hearth, a temperature of up to 1200°C being achieved by an upward blast of air supplied from two sets of bellows blowing alternately. Periodically liquid iron was run off through the tap-hole into a principal furrow formed in a bed of sand, called the sow, and its lesser branches the pigs (hence the term pig-iron). The slag (impurities and unreduced ore), being lighter than the molten iron, was drawn off last over the slag-dam. It has been estimated that the furnace was capable of producing about two tons of pig-iron per day, which, owing to its high carbon content, was hard and brittle and normally required further refining. For this purpose, apart from some casting and forging on a small scale, it was the policy at Bonawe to ship the rough bars of pig back to commercial plants in England.

Water for the ironworks was led from the River Awe about 1 mile (1.6km) to the east by means of an aqueduct, turning at right angles at the furnace to drive the water-wheel. Supplementary supplies were held in two reservoirs situated on the high ground near the manager's house and adjacent to the upper terrace of workers' dwellings.

Information from ‘Monuments of Industry: An Illustrated Historical Record’, (1986).

Publication Account (1986)

Bonawe Ironworks, situated close to the s shore of Loch Etive by Taynuilt village, is one of the most extensive and best-preserved relics of the early iron industry in Britain. It was established in 1752-3 by Richard Ford and Company as an offshoot of their works in Furness, and leases of the site and wood rights were agreed with the above-mentioned Sir Duncan Campbell and the 3rd Earl of Breadalbane for a period of 110 years. Haematite ore was brought in by sea from Lancashire and Cumberland, and a rotational system of coppicing was developed for the manufacture of charcoal, charcoal-burning stances being found in many of the natural woodlands around this part of Argyll.9 After expiry of the original lease in 1863, a new agreement was negotiated with Alexander Kelly of Bonawe, but the furnace finally closed in 1874.

As well as the furnace and storage sheds, the company erected a manager's house, workers' dwellings, and numerous ancillary buildings, which included a school, a church, a jetty and a truck-store, creating in effect a self-contained industrial community.

At the heart of the complex are the manufactory buildings, all of which occupy bankside positions on the sloping site, thus utilising the changes in level to assist what was essentially a gravity-feed process. They are solidly built of lime-mortared random or coursed rubble masonry, chiefly of the local granite, but numerous features betray their Lake District origins.

The charcoal sheds, or coal-houses, are spacious, well ventilated barn-like structures covered with open timber roofs of tie-beam construction carried down over the side-ranges as catslides. Loading-doors were situated in the rear walls, and unloading-doors, at the lower ground-level, at the front, whence the charcoal was barrowed or carried to the charging-house. The iron-ore shed, lying along the contours just NE of the charcoal sheds, was designed to be filled and emptied in a similar manner once the shipments of iron-ore had been carted up the hill from the jetty.

The blast-furnace is typical of the kind used during the later charcoal phase of the industry in Britain. The furnace openings have cast-iron lintels inscribed Bunaw. F. 1753. Apart from considerations of stability, the size and shape of the furnace were determined by the need for an adequate insulating core to reduce heat-loss and by the shaft within, whose design had to ensure a good draught and likewise prevent the friable charcoal from being crushed by an overweight of iron-ore.

The blowing-house, casting-house, store and smithy enclosing the furnace on its Nand w sides are now ruinous, but the pitched roofs formerly covering these important ancillary structures can be traced by the socket-holes in the furnace walls for the roof-timbers-roofs, incidentally, which would have given an entirely different outward appearance to the furnace compared with today. Excavations have revealed the granite base-blocks of a blowing engine introduced at some time in the 19th century to replace the original leather bellows. Both types were powered through a camshaft worked by a low breast-shot water-wheel mounted in a pit and wheel-house along the E side. The floor of the casting-house was found to be divided by a stone kerb into a part-metalled area to the N and a bed of fine sand to the s.

The rear s wall is insulated from the earth bank and retaining wall by a narrow V-shaped cavity, which has a stone conduit running along its base and that of the casting-house-presumably for collecting seepage. At the upper level, the charging house and furnace were connected across the cavity by means of a joisted timber bridge (hence the alternative name bridgehouse), and by relieving arches on the side-wall. Directly beneath the bridge a long narrow chamber, carried on a joisted floor, was contrived within the cavity. Approached from the E by an external ramp, it probably served as a bothy for the furnace-keeper during the smelting operations, and possessed the amenity of a window and a fireplace set in the retaining wall, with horizontal flues issuing from the side-walls.

The principal manufactory buildings have been described approximately in the sequence in which they occur in the smelting process. Prior to this, the three ingredients-iron ore, charcoal and limestone-underwent certain pre-treatment. Thus, the ore was washed, roasted and crushed to reduce its sulphur content and other impurities. The limestone was also broken down, and adequate stocks of charcoal had to be prepared, customarily supplied to the warehouses in 1 ½ cwt. (76 kg) bags and stacked there in dozens. It was also normal practice to pre-heat or season the furnace about a week in advance; the hearth area had to be relined where necessary and the apertures forming the tuyere and the tap-hole then sealed.

At the commencement of the smelting-operations the raw materials were assembled in the charging-house and measured in the correct proportions—the ore and limestone by weight, and the charcoal by volume—after which they were carried over the bridge and fed into the furnace shaft to its full height. Once the furnace was put into blast, the campaign (to use the trade term) was continuous, with recharging taking place constantly over a period lasting from about late autumn until early summer. Aided by a limestone flux for removing non-metallic impurities, the charge was heated and reduced to molten metal as it moved down the structure towards the hearth, a temperature of up to 1200°C being achieved by an upward blast of air supplied from two sets of bellows blowing alternately. Periodically liquid iron was run off through the tap-hole into a principal furrow formed in a bed of sand, called the sow, and its lesser branches the pigs (hence the term pig-iron). The slag (impurities and unreduced ore), being lighter than the molten iron, was drawn off last over the slag-dam. It has been estimated that the furnace was capable of producing about two tons of pig-iron per day, which, owing to its high carbon content, was hard and brittle and normally required further refining. For this purpose, apart from some casting and forging on a small scale, it was the policy at Bonawe to ship the rough bars of pig back to commercial plants in England.

Water for the ironworks was led from the River Awe about 1 mile (1.6 km) to the east by means of an aqueduct, turning at right angles at the furnace to drive the water-wheel. Supplementary supplies were held in two reservoirs situated on the high ground near the manager's house and adjacent to the upper terrace of workers' dwellings.

RCAHMS 1986, visited 1960-75

Watching Brief (June 1998)

NN 0098 3187. A watching brief was conducted in June 1998 during the excavation of a drainage trench on the S side of the western charcoal shed and the digging of post-holes for a fence around the lade below the furnace. The work was recorded by photographs, notes and measured sketches.

Although the holes and drainage trench were too small to result in any detailed conclusions, they were useful in showing the general types of deposits around the site, especially the presence of well-preserved organic matter to the S of the western charcoal shed.

Publication Account (2007)

Bonawe is said to be the most complete site of a charcoal fuelled ironworks in Britain with extensive remains of an 18th/19th century ironworks employing at its peak 600 people. It was the second last and largest in the West Highlands, selected for its extensive forests of oak and birch which provided the charcoal for the smelting. Limestone obtained locally was used as a flux.

The furnace was built for Cumbrian ironmaster Richard Ford, who founded the Newland Company of Furness. The iron lintels over the tap holes are dated 1753 and 1757.The iron ore was imported both from Lanarkshire and Cumbria and shipped to nearby piers on Loch Etive, including Kelly’s Pier. The pig-iron produced was shipped back to forges in the south for making into finished products, and cannon balls produced at Bonawe were used in the Napoleonic Wars. The works were in almost continuous production for 120 years until they closed in 1876.

The blast for the furnace was obtained by large bellows, originally powered by a waterwheel fed by a lade, now dry, almost a mile long from the Awe to the wheel pit. The low breast-shot wheel existed up to the time of the second world war when it was removed for scrap. Materials were conveyed around the site by barrows along early tramways made from slate tracks.

The site, which included cottages for workers and Bonawe House, the furnace manager’s residence, is now

under the care of Historic Scotland.

R Paxton and Jim Shipway 2007b

Reproduced from 'Civil Engineering heritage: Scotland - Highlands and Islands' with kind permission from Thomas Telford Publishers.

Watching Brief (25 June 2008)

NN 0090 3191 and NN 0093 3190 A watching brief was maintained on 25 June 2008 during the excavation of two small holes for telegraph poles, just NW of Bonawe Iron Furnace. The excavations re-used and slightly enlarged existing holes. Stone seen in one hole may have been demolition debris or structural remains, while the other hole was dug through a layer of slag to natural subsoil.

Archive: RCAHMS (intended)

Funder: Historic Scotland

Alan Radley (Kirkdale Archaeology), 2008

Publication Account (2009)

The website text produced for Bonawe webpages on the Forest Heritage Scotland website (www.forestheritagescotland.com).

Introduction: From wood to iron

Muckairn Wood, which included the present day Glen Nant National Nature Reserve, supplied one of the most successful charcoal blast furnaces in the Scottish Highlands.

In the mid 18th century the location of a furnace to make iron was often not decided by where the iron could be found, but where there was a good supply of trees. Charcoal was the fuel for the furnace, made by burning trees in a special process. The oak and birch trees in Muckairn Woods were one of the main sources of charcoal for nearby Bonawe Furnace.

In 1752, an English iron company made an agreement with Duncan Campbell of Lochneill to lease land to build the furnace and to use his woods for making charcoal. The lease agreement lasted for 110 years.

The woods needed to be carefully managed so that the trees would not run out. The iron company achieved this by a system of rotation coppicing.

Lochneill may have been foolish to have agreed to a long contract. Nearby landowners provided extra charcoal on short lease agreements, making more money as the furnace became more successful. Sadly, many of these other woods were not managed as well by the landowners and have not survived.

Today you can enjoy a walk amongst the oaks of Muckairn woods, possibly thanks to the long contract allowing the iron company to plan its use of the trees to the fullest.

People Story: Jobs for the natives!

In 1836 Lord Teignmouth travelled and wrote about the coast of Scotland. His mention of Bonawe suggests that the iron industry did nothing for the Highland views.

"The scenery is yet more disfigured by the charring-mills (charcoal making), which are seen smoking amid the spreading sense of desolation"

Lord Teignmouth (1836) in "Sketches of the Coast"

He does suggest, however, that the industry was important for the locals. While staff brought in from England undertook the main furnace operations, locals undertook other jobs connected with the industry. This included the charcoal making and its transport to the furnace. He describes the leasing of the woods as

" ...a most profitable undertaking to the company, as well as advantageous to the natives of the country by affording them constant employment"

Same as above

Little is known, however, about the people who lived and worked in connection to the furnace over its long lifetime. The furnace finally closed in 1876.

Evidence Story: What's left behind? The evidence for charcoal making

Evidence for the making of charcoal still exists on the forest floor of Muckairn Wood if you can discover it.

Amazingly it takes 6 to 8 tons of trees to make only 1 ton of lump charcoal. It was therefore practical that the charcoal be made in the forest; the charcoal was easier to transport to the furnace than the trees. The charcoal was made in a kiln or charring mill, usually built on an oval or D-shaped platform made from earth and mud. The logs were stacked around a central wooden post and then covered in earth and vegetation. The central post was then removed and a fire placed in the gap. The burning process took between 2 to 10 days, slowly allowing oxygen in to the fire to create the charcoal.

The evidence mostly remaining of this process is the many earth platforms scattered over the forest floor. You can explore our Nant trail and see if you can discover any. Many are located beside the River Ant.

Watching Brief (28 July 2010)

NN 0096 3191 A watching brief was undertaken on 28 July 2010 during the excavation of two small holes near the ticket office for the installation of signs. No deposits other than modern landscaping were excavated and no finds or features of archaeological significance were recorded.

Archive: RCAHMS (intended)

Funder: Historic Scotland

Paul Fox – Kirkdale Archaeology

Information from OASIS ID: kirkdale1-249875 (P Fox) 2010