Pricing Change

New pricing for orders of material from this site will come into place shortly. Charges for supply of digital images, digitisation on demand, prints and licensing will be altered.

East Wemyss, Sliding Cave

Cave (Iron Age), Pictish Symbol Rock Carving(S) (Pictish)

Site Name East Wemyss, Sliding Cave

Classification Cave (Iron Age), Pictish Symbol Rock Carving(S) (Pictish)

Alternative Name(s) Wemyss Caves; Sloping Cave

Canmore ID 53978

Site Number NT39NW 8

NGR NT 3461 9727

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/53978

- Council Fife

- Parish Wemyss

- Former Region Fife

- Former District Kirkcaldy

- Former County Fife

East Wemyss, Sliding Cave, Fife, Pictish rock carvings

Measurements:

Stone type: sandstone

Place of discovery: NT 3461 9727

Present location: in situ.

Evidence for discovery: Simpson and others visited the caves in 1865.

Present condition: weathered.

Description

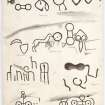

In this cave there are incised a rectangle symbol, a double-disc and two serpents.

Date range: sixth to eighth century.

References: Simpson 1866; Ritchie & Stevenson 1993; Fraser 2008, no 81.4

Compiled by A Ritchie 2016

NT39NW 8 3461 9727

(NT 3461 9727) Sliding Cave (NR)

OS 25" map, (1961)

Symbols carved on the walls of the Sloping Cave are the rectangular symbol (repeated twice) and the double-disc symbol without the Z-shaped rod.

J R Allen and J Anderson 1903.

Publication Account (1933)

Sculptures in Caves, Wemyss.

On the shore in the neighbourhood of East Wemyss are five caves, the walls of which are marked with a great number of devices, some similar to those found on sculptured slabs. The caves and their markings are fully described and illustrated with drawings in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, v (1866), p. 521, &c.; Proc. Soc. Ant. Scot., xi (1874-6), pp. 107-20; Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, pp. 370-3.

RCAHMS 1933.

Field Visit (6 October 1954)

A much-weathered cave with a steeply sloping floor. The ornament mentioned above was not seen.

Visited by OS (J F C) 6 October 1954.

Field Visit (19 February 1960)

Sliding or Sloping Cave.

Visited by OS (A L F R) 19 February 1960.

Publication Account (1987)

The caves formed in the sandstone cliffs to the northeast of East Wemyss have been the focus of antiquarian and archaeological interest since 1865 when Professor James Young Simpson visited them and found their walls 'to be covered at different points with representations of various animals, figures and emblems'. What particularly excited the discoverers was that several of the the incised markings could be compared to those on Pictish symbol stones, the significance of which was at that time becoming apparent as a result of John Stuart's work on cataloguing them. Careful drawings of the markings were made for the second volume of Stuart's 'The Sculptured Stones of Scotland' (published in 1867) and these, amplified by photographic surveys in the early years of this century and again in the 1920s, have provided the basic record. Between 1984 and 1985 further drawing was undertaken, and it is clear that several areas of carvings have been lost, and perhaps even more sadly other markings in 'Pictish style' have been added; here we list only the most interesting and apparently authentic markings.

...The Sliding Cave should only be visited with great care, but there are rectangular markings on one wall and double-disc on the other. A torch is essential.

Information from ‘Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: Fife and Tayside’, (1987).

Note (May 2017)

On the walls of the cave, only the shadows are the truth

The caves at East Wemyss in Fife contain a large number of carved symbols, mainly Pictish but also Christian and Viking, which have fascinated antiquarians and researchers ever since they were first recorded in 1865. Of the six caves known to contain carvings, only four feature the Pictish carvings for which the site is famous: these are known as Court Cave, Jonathan’s Cave, Sliding Caves and West Doo Cave.

We are used to seeing Pictish carvings as prominent and accomplished public works of art: think of the detailed symmetry and storytelling found on cross slabs or the flowing, linear depictions of people, animals and symbols carved into stones standing proud in the landscapes of northern Scotland. The Wemyss Caves carvings are very different. Hidden in the dark recesses of the caves, they are a collection of symbols and figures that vary in skill and style from the accomplished to the “rough and ready”. The impression is of multiple individuals coming to the caves to make their mark but their identity and reasons remain a mystery. The only similar site that we know of is Sculptor’s Cave, Covesea but the layout and use of that site is very different: Wemyss has many more symbols, but none of the ritual remains found at Covesea.

Symbols from other eras can also be found, ranging from early Christian crosses to early modern graffiti. Two of these carvings are particularly enigmatic; a small human figure holding a rod, sword or club, and a boat with high prows, a row of five oars and a large tiller. These are cut in a different style to the Pictish carvings and may date from the period when Vikings roamed the Firth of Forth.

The earliest photographs of the carvings were likely taken in 1902 by the photographer John Patrick. Born in Buckhaven, Fife in 1831 John Patrick first became a baker and then moved to Leven where he opened a business as a bookseller, before becoming interested in photography. He opened his first studio in Leven at the age of 22 and later had premises in Kirkcaldy and Wemyssfield. In 1884 he opened an Edinburgh studio. He was a member of the Edinburgh Photographic Society and contributed to several exhibitions, specialising in landscape and portrait photography. He was a writer and a painter, and was very interested in archaeology and history, documenting and photographing sites in Fife like the standing stones at Lundin Links and a cist found at Denbeath.

In 1902 John Patrick took a series of photographs of the symbols and caves at East Wemyss, and prepared articles for publication in The Reliquary and Illustrated Archaeologist in 1905 and 1906 where he discussed the meanings of the symbols, hoping his photographs and research would provide a detailed record and to ‘cause something to be done for the protection from injury of so remarkable a series of early sculptures’. In a later account his daughter, Jessie Patrick Findlay, who often accompanied her father to the caves describes his interest: ‘My father had made the study of the Caves of Wemyss emphatically his own. He was a native of the district’.

Photographing the carvings was difficult, there was no natural light and he had to use a magnesium wire or ribbon to provide the necessary light for a long-exposure photograph on to a glass plate negative. His photographs are now an invaluable record of the carvings and caves, especially since some are no longer accessible or damaged. John Patrick retired as a professional photographer in 1912 and died in Kennoway 1923.

All things are subject to decay and change

John Patrick’s plea for ‘something to be done for the protection from injury’ of the site is even more timely today. The caves face multiple threats from coastal erosion, rising sea levels, vandalism and the soft and fragmentary nature of the rock itself which is vulnerable to erosion, delamination and collapse at both the small and the large scale. Over the past century or so, almost all the caves have experienced significant rockfalls or landslips. As a result, West Doo Cave and Glass Cave have been substantially filled in and carvings have been lost in Jonathan’s Cave.

These ongoing and unpredictable processes are a threat to the caves and their carvings but are also a threat to visitors. The caves and the area around them cannot and should not be considered safe to enter. Anyone considering entering the caves should make themselves aware of the potential risks and assess the situation on the ground.

The Save Wemyss Ancient Caves Society (SWACS) leads tours to view the carvings in the summer, if conditions permit. Details can be found on their websites via the link below. With the help of a number of national and local bodies including Historic Environment Scotland, Fife Council, the SCAPE Trust, the Wemyss Estates (the owners of the sites) and the Heritage Lottery Fund, SWACS have also developed the first ever management plan for the site which lays out a scheme of action to record and protect the caves and their carvings.

Acknowledging the important foundations that John Patrick and others have left us, this management plan has driven a major digital recording project for the caves and their and the results can be seen on the Wemyss 4D website. Now anyone can explore the caves at the click of a mouse using the legacy provided by Wemyss 4D.

The HES archive hold a collection of original prints by John Patrick as well as glass negatives illustrating the caves, along with other material including drawings and rubbings from 1866 in the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Collection as well as modern survey material available on Canmore and for consultation in our Search Room.

Deirdre Cameron – Senior Casework Officer and Kristina Watson - Archivist

Excavation (10 July 2019 - 18 July 2019)

NT 34400 97000 In July 2019, a partnership of the SCAPE Trust, Save the Wemyss Ancient Caves Society and the University of Aberdeen carried out targeted excavation in Court Cave, Doo Cave and Sliding Cave; three of the seven Wemyss Caves that form part of scheduled monument SM 817. The research objectives addressed two overarching questions. Firstly, to learn something of the potential significance of the buried archaeological resource in Court Cave and Doo Cave because no modern investigations have ever taken place in them; and secondly, to further investigate stratified deposits in the Sliding Cave previously dated to the 3rd-5th century AD, which have potential to contribute to wider research of national significance about the origin and dating of the Pictish symbols.

Two trenches inside Court Cave recorded shallow compacted layers of mostly relatively recent date and found bedrock approximately 0.3m below the current cave floor surface. However, a single sherd of a Scottish White Gritty Ware green-glazed jug (14th-15th century) and five conjoining sherds from a Yorkshire Type Ware green-glazed jug (13th–14th century) were recovered from a context directly overlying the bedrock floor in Trench 2 at the side of the main entrance chamber. A trench just outside the entrance to Court Cave was excavated 2.3m to bedrock, and contained deeply buried midden material including animal bone, marine shell, and 5 pottery sherds from a possible Northern English Ware green-glazed jug (14th-15th century), as well as evidence of iron working in the form of slag and a fragment of tuyère. This is the first time that evidence for iron smelting or smithing has been identified in the Wemyss Caves, and given the location of the midden and the lack of deposits inside Court Cave, there is a real possibility that the midden derives from activities taking place inside the Court Cave in the medieval period. Scientific dating of the tuyère and a sample of animal bone will hopefully provide more certainty on the date of activities resulting in the midden.

A trench located at the back of the Doo Cave revealed an unexpected discovery of rock cut niches and a possible pit carved into the bedrock floor of the cave. These were buried beneath nearly 2m of in-wash from the back of the cave, which contained only relatively modern finds. The in-wash sediments are likely to be the result of the collapse of the West Doo Cave in 1914. It is puzzling that these recent deposits were found on clean bedrock floor. A thin layer of sand and pebbles filling features cut into the bedrock may hold the answer. In the early 20th century, changes in the coastline resulted in the migration of the beach right up to the mouth of the Doo Cave, putting the cave interior in reach of the erosive power of the sea.

The re-excavation of the 2004 Time Team trench in the Sliding Cave successfully located the 3rd-5th century occupation horizon and sampled additional material from it for analysis and radiocarbon dating. The excavation also discovered a bone-rich layer below this occupation horizon that lay beyond the limits of the original trench. Both of these cultural deposits were present in a second trench opened up towards the centre of Sliding Cave, showing that extensive archaeological deposits fortuitously survive in one of the less accessible of the Wemyss Caves.

Archive: NRHE

Funder: Historic Environment Scotland

J Hambly, M Arrowsmith and G Noble - SCAPE Trust, Save the Wemyss Ancient Caves Society (SWACS) and University of Aberdeen

(Source: DES Vol 20)

OASIS ID: thescape1-504522