Pricing Change

New pricing for orders of material from this site will come into place shortly. Charges for supply of digital images, digitisation on demand, prints and licensing will be altered.

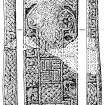

Bute, Rothesay, Rothesay Castle, Cross Slab

Cross Slab (Early Medieval)

Site Name Bute, Rothesay, Rothesay Castle, Cross Slab

Classification Cross Slab (Early Medieval)

Canmore ID 301961

Site Number NS06SE 3.02

NGR NS 08758 64601

NGR Description Site of discovery in NW tower.

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/301961

- Council Argyll And Bute

- Parish Rothesay

- Former Region Strathclyde

- Former District Argyll And Bute

- Former County Buteshire

Artefact Recovery (1816)

Reference (1848)

Reference (1864)

Reference (1867)

Photographic Survey (1975)

Photographic Record (1991)

Measured Survey (March 1994 - April 1994)

Reference (1996)

Reference (2001)

A rectangular cross-slab of sandstone was found in Rothesay Castle in 1816, re-used in two fragments at the foot of the stair in the NW tower (1). It remained there until some time after 1903 when it was moved to Bute Museum. It is damaged at the top and foot and broken obliquely at mid-height, lacking a triangular section to the right and a smaller one to the left, but the short faces preserved at the break appear to match closely. It measures 1.78m by 0.51m and tapers in thickness from 135mm to 110mm, but this reduction appears to be due mainly to greater wear in the upper fragment.

The slab is carved on the edges and one face in false relief between edge-mouldings which vary from 20mm to 30mm. The face is filled with a Latin cross outlined by mouldings which merge into a horizontal key-pattern (RA 923) in the rectangular base, itself enclosed by an outer moulding. The cross has narrow oval armpits which form splayed arms, and at the centre of the head and at each side of the top of the shaft there is a roundel containing interlocked triple spirals. The remainder of the cross-head is filled with interlace which is continuous with an eight-cord plait (RA 513a) in the upper part of the shaft. The remainder of the shaft is divided into two square panels, the upper one containing a key-pattern (RA 919) and the other an eight-cord plait (RA 506). Flanking the top of the shaft there are beasts' heads, much damaged by flaking, which are attached to the mouldings of the lower arm of the cross. Below the one to the left there is an incomplete motif which may represent an interlaced animal, followed by a section of plaitwork and at the foot a squatting creature holding a fish. To the right there is an incomplete strip of plaitwork with loops at the sides (variation of RA 551) above what appears to be a man attacked by a beast. The left edge of the slab is filled with double-beaded interlace (RA 574 combined with 568; RA 522), and the right edge has two panels of interlace, also double-beaded (RA 581; RA 519) divided by an incomplete key-pattern (RA 886).

Footnotes:

(1) McKinlay, J, An Account of Rothesay Castle (2nd ed., 1818), 22; Wilson, J, Guide to Rothesay and the Island of Bute (1855), 31. Stuart 1867, 36 (followed by Hewison 1893, 1, 233 and Allen and Anderson 1903, 3, 414) wrongly says St Brieuc's Chapel, apparently referring to the choir of the old parish church which was cleared of debris in 1817.

J McKinlay 1818, 22; J Wilson 1848, 31; Reid, Bute, 32 and pl. opp. p.288; Stuart 1867, 36 and pl.72; Hewison 1893, 1, 233 and pl. opp. p.232; Allen and Anderson 1903, 3, 414-16; Cross 1984, B39; Speirs 1996, 60-1.

I Fisher 2001, 80-1.

Characterisation (11 August 2010)

This site falls within the Rothesay Town Centre Area of Townscape Character which was defined as part of the Rothesay Urban Survey Project, 2010. The text below relates to the whole area.

Historical Development and Topography

The Town Centre Area of Townscape Character comprises the main historical core of Rothesay, which grew up around the 13th-century castle, unique to Scotland in its circular form. From these early beginnings, Rothesay became a Royal Burgh in either 1400 or 1401 – the exact year is not entirely clear from documentary evidence. The castle was much altered during the following centuries, and the town itself expanded along the High Street towards 16th century St Mary’s Chapel to the south and the shore/Harbour in the north, in a traditional linear burgh form.

In the late 17th century (c.1680), the Marquess of Bute established a residence in the town, looking onto the Castle from the High Street. It was the second Marquis of Bute who, in 1816-18, carried out the first of many restorations to the castle. The town gradually spread out from the High Street during the 17th and 18th centuries. By the mid-18th century, the town stretched as far east as Bishop Street, as far south as Minister’s Brae and as far west as Mill Lade.

Two phases of land reclamation changed the focus and whole axis of Rothesay from north-south along the High Street to east-west along Montague Street in the mid- to late 18th century, and subsequently Victoria Street in 1839-40, which was built on the site of a former boatyard. The majority of the town centre was redeveloped as a result of these reclamation schemes, with key public buildings locating here in the 19th century, such as the court house on Castle Street built to designs by James Dempster in 1832 with later 19th century alterations, and the Baroque-style post office on Bishop Street, dated 1896. The harbour and pier grew in significance as a result of this shift, and its growth, along with the great rise in Rothesay’s popularity as a seaside tourist resort during the 19th century, saw the shoreline become the focus for the town’s growth rather than further inland.

On the whole, the town centre developed in a fairly ad hoc manner, as would be expected in a historic town centre. However, the area is largely a mid- to late 19th century Victorian creation, particularly with the reclamation of land along the shore, creating the Esplanade, with the later addition of the Winter Gardens, by Walter MacFarlane & Co’s Saracen Foundry in collaboration with the Burgh Surveyor, Alexander Stephen in 1923-4.

Numerous hotels were established here in the mid-19th century: Victoria, which has its original lamp standards and decorative floor tiling at the entrance; Esplanade, with double-height box bay window to Victoria Street and single-height to Guildford Square; Royal, has marbled columns flanking its entrance on Albert Place; Bute House, retains a timber Victorian shop front at ground floor with arched windows and entrance on curved corner; and Guildford Court, which has a modern flat-roofed canopy resting on original decorative cast-iron brackets over its entrance on Guildford Square. Several tenements were built along Victoria Street, Albert Street, East and West Princes Street. As a result of the numerous multiple occupancy buildings, the Town Centre Area of Townscape Character is a high density area, with mostly small plot sizes throughout.

Historically, as with most town centres, the area has been continuously redeveloped and infilled as the needs of the population grew and changed. The area around the Castle has probably seen the greatest deal of redevelopment in the 20th century, with the west and south sides surrounding it being wholly redeveloped with the building of Bute Museum in 1925-6 to designs by local architect Andrew Morell McKinlay, telephone exchange built in 1966 by John R Hunter (Building Contractors) Ltd, leisure centre and library designed by Robert B Rankin & Associates in the 1970s and job centre and Inland Revenue office also built in the 1970s. Guildford Square was created as a public open space following the demolition of two banks and a hotel in the 1990s.

Present Character

There are examples of each stage of Rothesay’s growth and development throughout the Town Centre Area of Townscape Character. Rothesay’s earliest beginnings are represented by the 13th century Castle. The 17th century Bute townhouse, with its crowstepped gables and projecting stair tower, is a fine survival of typical Scottish burgh architecture dating from this period. Much of the street layout in the area has survived unaltered despite later developments.

There are undoubtedly some remnants of 18th century buildings in the Watergate and Store Lane area, probably previously associated with former harbour activities. Some early 19th century single-storey-plus-attic cottages survive, much-altered, at Nos 19-27 Bishop Street, but the majority of the area dates from the huge Victorian expansion to provide tenement and hotel accommodation for the influx of tourists from the mid-19th century.

Many of the tenements built in Rothesay during the tourism boom display features similar in style to those tenements of the town’s middle-class Glaswegian visitors. The use of the same red sandstone, often with carved stonework including shaped pediments above entrance doors to shared tiled stairwells or ‘wally closes’ with decorative cast-iron balustrades and often stained glass windows to internal doors.

One of the key features of the Town Centre Area of Townscape Character is the extensive use of splayed corners to those 19th century buildings on street corners nearest to, or having views towards, the shore. This not only opens up and provides views to the sea for as many areas of the buildings as possible, but also maximises light into the buildings in what is a fairly densely packed urban fabric. The extensive use of bay windows, particularly along shoreline tenements on East Princes Street and Argyle Street, serves the same purpose, as elsewhere in Rothesay.

While most of the buildings, especially the tenements, are of a typically Scottish form, there are some more unusual or distinctive building styles dotted across the area. One example is James Hamilton & Son’s French Baroque-style Duncan’s Halls, built in 1876-9 at Nos 19-25 East Princes Street to provide a range of public halls and rooms for entertainment, and housing the town’s Palace Cinema from 1913 to 1963 when it became a bingo hall. James Dempster’s 1832 court house building on Castle Street is distinctive with its heavily battlemented parapet and chunky stonework, in contrast to the finer stonework of the surrounding tenements.

Throughout the Town Centre Area of Townscape Character Victorian cast-iron lamp posts, painted blue, with the town coat of arms still remain, though some may have been reinstated. These lamp posts can be found along the main seafront of the town, into the East Bay Area of Townscape Character and Serpentine and West Bay Area of Townscape Character.

Rothesay town centre contains a wide range of shop front styles, with many still surviving from its Victorian heyday. These consist of timber-framed shop windows and fascias above, often with moulded/carved columns and pilasters between window panes. In general these shop fronts also retain their original mosaic tiled lobbies within their recessed entrances. Rothesay also retains a fine example of corporate shop front design with the former Woolworths building at Nos 85-99 Montague Street, designed by B C Donaldson of London. Built in 1938, the store was designed to a pattern to ensure shoppers recognised the store as a modern Woolworth’s shopping experience at first sight. The shop front retains its traditional wooden-framed swing doors to its entrance, and demonstrates typical features of 1930s architecture, with a stepped roofline to the front elevation, and slightly projecting vertical stonework between windows at upper floors giving height to the building. Built in 1979, No 41-45 Montague Street (currently Lloyds TSB) is an unusual design by Roxby, Park & Baird consisting of a series of elements from Scottish architecture such as crowsteps, corbelling and a harled and whitewashed finish.

More modern features can be found in some distinctive 1960s/1970s tiling to a number of shop fronts in Montague Street and High Street. The manufacturer of these tiles has not yet been indentified, but they may be of local origin or bulk purchased by shopfitters working in the town.

Information from RCAHMS (LK), 11th August 2010