Pricing Change

New pricing for orders of material from this site will come into place shortly. Charges for supply of digital images, digitisation on demand, prints and licensing will be altered.

Druminnor Castle

Castle (Medieval)

Site Name Druminnor Castle

Classification Castle (Medieval)

Alternative Name(s) Druminnor House; Castle Forbes; Drumminnor Castle Policies

Canmore ID 17651

Site Number NJ52NW 14

NGR NJ 51315 26403

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/17651

- Council Aberdeenshire

- Parish Auchindoir And Kearn

- Former Region Grampian

- Former District Gordon

- Former County Aberdeenshire

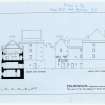

Druminnor, 1440, 1577. The present palace-block originally had an L-plan tower-house to the north-west. The main

entrance is, Huntly-like, in stair-tower at north-east, adorned with three armorial panels over the door. From the courtyard the main block appears subdued but rears up four storeys on the dramatic south front, owing to the fall in the ground. Tiny dormers pierce the wallhead. Nothing now remains of Archibald Simpson's wing of 1815 which had dramatic pointed gables and three good dormer-heads; house guests in the 1950s were each invited to remove a stone by the Hon Margaret Forbes Sempill who restored the castle with advice from Ian G Lindsay.

The Forbes house, the original Castle Forbes until the name passed to the new castle on the Don at Putachie (qv Keig), Druminnor was the scene of an infamous dinner during the Troubles of the mid-17th century at which 20 Gordons were

murdered by their hosts. That a similar story is attached to Castle Fraser - 'Hospitality or no' said Lord Fraser, 'if I smell treachery I'll touch my beard. Then stab every man!' Inadvertently he did and 20 dead Gordons lay stretched on the floor -

rises from the general tenor of the times and the fact that many people thought that there were at least 20 Gordons who would be the better for the letting of a little life out of them!

Harry Gordon Slade, 'Proc Soc Antiq Scot', 1977

Taken from "Aberdeenshire: Donside and Strathbogie - An Illustrated Architectural Guide", by Ian Shepherd, 2006. Published by the Rutland Press http://www.rias.org.uk

NJ52NW 14.00 51315 26403

NJ52NW 14.01 5102 2644 Home Farm

NJ52NW 14.02 5127 2710 Mains of Druminnor

NJ52NW 14.03 5127 2693 Mains of Druminnor Cottages

NJ52NW 14.04 5081 2639 kennels

NJ52NW 14.05 5119 2624 West Lodge

NJ52NW 14.06 51512 26602 East Lodge and gate piers

NJ52NW 14.07 51231 26327 Garden Cottage

NJ52NW 14.08 51369 26417 Garden and garden walls

NJ52NW 14.09 51523 26538 Graveyard

(NJ 5130 2639) Druminnor House (NAT)

OS 6" map, (1959)

For previous history of Druminnor House and the derivation of its name see NJ52NW 22.

The original rectangular keep-tower of Druminnor, built by Alexander, 1st Lord Forbes in 1440 and licensed on May 4th, 1456, still remains basically as it was built. It was slighted after the battle of Tillyangus in 1571 and repaired in 1577, the latter date being cut on a stone above the door arch bearing the arms of William, 7th Lord Forbes - 1547 to 1594 - set in the circular staircase tower which was probably an addition at that time. Attached to the older building is a wing erected in 1815. The old castle is being restored to its original state by the owner, Miss Forbes-Sempill.

Simpson (1949) believed that the original building had been destroyed and he quotes a description by John Leyden in 1800, recorded by Sinton (1903), wherein he states that he saw 'the ruins of Drummenir Tower which the proprietor had demolished ... It consisted of a square united to half a square, which contained the staircase.'

MacGibbon and Ross (1887-92) name it as 'Druminnor Castle'.

J F Wyness 1959; W D Simpson 1949; J Leyden 1903; D MacGibbon and T Ross 1887-92.

Druminnor Castle, as described and planned by Wyness (1959), has now been restored to its original condition.

Visited by OS (RL) 21 September 1967.

(Location cited as NJ 5130 2639 and classified as Site of Regional Significance). Only the staircase tower and hall block remain of a much larger building, a great palace-house similar to Huntly Castle (NJ54SW 9). The great square tower was demolished in 1800 after which a Baronial villa was built in 1815, which was in its turn demolished in 1960. Only the foundations remain of the extensive courtyard ranges. Now restored to its former condition wherever possible.

Masons: John Kemlock and William of Ennerkype, 1440: architect, Archibald Simpson, 1815.

Memorandum dated 4 July 1440; livence dated 4 May 1456; sacked 1571; alterations 1577 and 1843.

NMRS, MS/712/35.

NJ 513 264 A programme of survey and recording was undertaken of the archaeology revealed in a series of trenches. These trenches had already been dug by the owner, with the intention of locating and assessing an extensive system of drains around the castle in the hope that these excavations would provide a solution to recent drainage problems that had been encountered. Initial site inspection showed that a wide range of archaeological features and deposits had been exposed.

Archive to be deposited in the NMRS.

Sponsor: Mr Alexander Forbes.

G Ewart and D Murray 2002

NJ 5131 2640 Watching briefs were kept during remedial works to combat drainage problems within and around the hall range, which is all that survives above ground of this mid-15th-century castle. This work was a continuation of a project started in 2001 to locate and unblock drains distributed around the castle's exterior (DES 2002, 8). In addition, a large trench was opened at the SW corner of the building to allow it to be strengthened by concrete buttressing. Excavation revealed the massive rubble foundations of the castle and evidence of a sequence of post-glacial processes associated with the nearby Kearn Burn.

A small trench was opened to determine whether any remains of a putative tower survived below a 19th-century mansion house that had been built against the NW corner of the castle, but which was demolished in the 1960s. No trace of either building was uncovered.

A trench, 12m N/S by 6.5m, was opened beyond the E wall of the castle to investigate several masonry features partially exposed on earlier occasions, and to determine whether this steeply sloping area had been terraced at some stage. Three walls of some antiquity were uncovered towards the N end of the trench, one of them

quite possibly a garden terrace wall. At the S end of the trench, near the SE corner of the castle, were the remains of a masonry building, the E wall of which had been thickened at some stage, probably to insert a fireplace. This building, which had a flagged floor, had been truncated by a modern drain on its S side.

Excavation within a small cellar in Garden Cottage, some 100m W of the castle, revealed a stone-lined passage in its E wall which defies interpretation. Possible explanations for the cellar include its use as an ice house or as a wheel pit for a mill pre-dating the presumed late 18th-century date for the cottage, although neither idea bears close scrutiny.

Sponsor: Mr Alexander Forbes.

J Lewis 2004

NMRS REFERENCE:

Owner: Lady Forbes

Architect: Adds. to old part by Archibald Simpson in 1815. Said to have been the original Castle Forbes built in 1456 & in its present state dating from 1577 - not to be confused with Castle Forbes, Keig Parish. (Source - Aberdeenshire 3rd Statistical Account. Pub. 1960)

House partically demolished. C.H.C April, 1961

Non-Guardianship Sites Plan Collection, DC23397, 1963.

Photographic Survey (May 1954)

Photographic survey by the Scottish National Buildings Record in May 1954.

Desk Based Assessment (2013)

NJ 5131 2642 As part of research into the archaeological potential of the area, an 18th-century estate plan was discovered, that included a block plan of Castle Forbes (now Druminnor) and a simple perspective sketch. Until now, only fleeting documentary references to the pre-1841 layout were known, from which it was deduced that the surviving building was part of a much larger complex, of which the ‘Old Tower’ was the principal element. The ‘Old Tower’ and the Kirk of Kearn were demolished around 1800. A new mansion was added in 1841 and the gardens remodelled. The 1841 building was in turn demolished in the 1960s. The perspective sketch is the only known image of ‘Castle Forbes’ prior to its 1841 renovation. The new plan confirmed that the medieval castle was far larger than the surviving fragment, consisting of two courtyards of buildings within a barmkyn, surrounded by extensive enclosures for gardens, orchards and a ‘cour d’honneur’. The ‘Old Tower’ was clearly not where it had been imagined, but the sketch confirmed that the documentary descriptions of it were broadly accurate. However, inconsistencies between the block plan, the sketch and the actual topography raised as many issues as they resolved.

As part of the Bennachie Landscapes community research initiative, the fieldwork group began investigating the former ground plan of Druminnor Castle. Trial trenches were laid out to locate the former wall-lines shown on the late 18th-century estate plans. Unfortunately, many of the earlier land surfaces had been removed during early 19th-century landscaping and rebuilding works. However, the trenches did identify features, in various states of survival, which indicated that further work will clarify the situation.

Grateful thanks are extended to Alex Forbes for sharing his historical and architectural knowledge, for his wonderful hospitality and for his great forbearance whilst his gravel car park was indelibly scarred by trenches.

Archive: Aberdeenshire Council HER and Bailies of Bennachie

Colin Shepherd, 2013

(Source: DES)

Excavation (May 2014 - October 2014)

NJ 5131 2642 Following the trial trenching reported last year (DES 2013, 15–16) further fieldwork was undertaken, May – October 2014, which has begun to confirm and clarify the ground plan of the 18th-century castle, which was largely demolished in the first half of the 19th century. The work has also begun to record features belonging to earlier phases of activity. These appear to demonstrate a slightly different alignment and plan, though further work is needed to confirm that proposition. This year’s work has demonstrated that more archaeological evidence survives from the castle than was initially suspected.

The N range of the lower courtyard foundations survive to demonstrate the accuracy of a small sketch plan incorporated within two 18th-century estate plans (until 2011, unrecognised). The slight construction of the walls suggests that they are unlikely to belong to a period much earlier than the late 16th century and it is therefore possible that this part of the castle was not added until that time. Two distinct floor surfaces, one

cobbled and an underlying one of beaten earth and associated with a small hearth, suggest the area was redesigned at some point. The later addition of a lower court would be stylistically in keeping for the area in the 17th century and may have occurred after the historically well attested dispute with the neighbouring Gordons of Huntly. Alternatively, a date of c1660,

when the hall block was being made more commodious, may be another option.

The outer wall of the N range overlies further structures, apparently not conforming to the later plan. Although not firmly sealed by the later wall, the relationship of deposits containing pottery dated to the 14th/15th and 15th/16th centuries to that wall supports the notion of a late 16th- or 17th-century date for it. The present surviving S range is considered to belong to

the mid-15th century, but the pottery assemblage noted above tends to confirm that this may not have been the first building on the site, as the name of ‘the Old Tower’, demolished in 1800, implies. Stylistically, the tower might be considered to have belonged to the later 13th or earlier 14th century.

Geologically, the site has proven both difficult and interesting. A basalt dyke may have been fundamental in determining the choice of site for the castle. Though now unnoticeable in its gentrified landscape setting, the dyke is likely to have presented a craggy eminence prior to the castle’s

construction. A levelling layer of sandstone debris underlies all other archaeological features and overlies the natural basalt bedrock and weathered sandstone subsoil. This layer may, therefore, represent initial levelling for the earliest medieval structures on the site.

A further trench revealed the foundations of the western ‘gatehouse’ range, which seem to match fairly accurately the position indicated on the estate plan. The foundations appear to have been reused to underpin a wall belonging to the 19th-century mansion, built after the demolition of the castle. This suggests that the layout of that later building did owe at least

something to its predecessor.

Finds included sherds from at least one Frechen ware (c1550–1700) vessel and a late 17th-century Dutch clay pipe bowl, conveniently deposited within the fill of a posthole, which was part of a structure outwith the probable limits of the castle. This area is shown on the estate plan of c1770 as containing trees and the structure may have been a garden feature. Future work will, hopefully, answer these and other

questions arising from this interesting site.

Again, tremendous thanks are owed to Alex Forbes for permitting access to his grounds, his hospitality and for his generous historical advice concerning the Forbes and other families of the area

Archive: Aberdeenshire Council HER

Colin Shepherd - Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source: DES)

Excavation (May 2015 - October 2015)

NJ 5131 2642 Three areas were investigated, May – October 2015, in order to clarify elements discovered in previous years (DES 2014, 16) and to try to locate the eastern perimeter wall of the castle plan as shown on two 18th-century estate maps. The perimeter wall proved elusive as the area where it is assumed to have stood appears to have undergone sweeping landscape changes in the 19th century; having been cleared to natural and then overlain with topsoil. However, a shallow but well-built minor drainage channel overlain with flat capstones was found at the W end of the trench. This possibly served one of the buildings (shown on the estate maps) lying in the service courtyard. The drain would have run directly across the courtyard, though along an apparently illogical flow-line.

The remains discovered N of the castle in 2014 were further investigated. This work demonstrated the survival of a substantial wall comprising an outset foundation course on the downslope side, coursed stonework and a rubble core made of small stones bonded by clay. The wall, measuring c1.2m wide at its base, appears to have been completely robbed out at either end. Abutting the surviving section of wall on its southern (upslope) side is a rectangular structure consisting of a basal outer row of large fieldstones enclosing a platform of clay-bonded rubble and measuring c2.7 x 2m overall. The purpose of this feature is unknown. Beneath this structure, and partially sealed by it, is a stone-lined pit. After heavy rain, this pit retains water and may have acted as a small cistern, though this remains to be confirmed. The wall is presumed to have acted as an outer enclosure for an earlier plan of the castle. Its alignment is out of true with the 18th-century plan (taken from the estate map) and the surviving S range, but lies parallel to other features discovered and with which it may have been contemporary. One of these features is another substantial stone-built structure (described below).

A third area was examined in order to elucidate the purpose of remains found at the edge of Trench 2 in 2014. These appeared to be structural features underlying the northern outer enclosure wall shown on the estate map. Once revealed, these related to the corner of a substantial building consisting of an outset foundation course, coursed stonework and a mortared rubble core. The structure’s wall measures c1.2m across its outset foundation course. This building appears to be one of those shown on the estate map. However, the northern enclosure wall linking this structure to the rest of the castle plan was feeble in comparison with this, presumably earlier, building and merely abutted it at a level much higher than the foundation course. Furthermore, the building appears to be aligned askew to the later castle plan, but to share its orientation with the wall noted above and a drain/path feature noted in earlier phases of the excavations. It might be suggested that the later plan, shown on the estate map and assumed to belong to the 17th century, was created by joining older extant features; the substantial building described here being one of those earlier features.

A number of dressed stones, complete and fragmentary (see below), have been found as backfill components in this area; this contrasts noticeably with other areas of the excavation. A doorway, in the corner of the building, poses certain difficulties with regard to its construction and may be a secondary feature.

Various pottery sherds, dated to between the 14th and 16th centuries, were found overlying the building and the wall described here, but none in securely stratified situations. However, one piece of fine, dressed masonry was found in a context sealed by the later (17th century?) northern enclosure wall noted above. This contained a mason’s mark, hitherto unrecognized at Druminnor.

Once again, sincere thanks are owed to Alex Forbes for his forbearance as yet more of his lovely policies are disturbed in the cause of archaeology, and for his words of historical wisdom and generous hospitality.

Archive: Moray and Aberdeenshire Council SMR

Colin Shepherd - Bennachie Landscape Fieldwork Group

(Source: DES, Volume 16)

Excavation (May 2016 - October 2016)

NJ 5131 2642 A fifth season work was undertaken, May – October 2016, at Druminnor Castle. Highlights included the total excavation of the surviving parts of an early corndrying kiln, radiocarbon dated to between 1035 and 1207 cal AD (SUERC-67036 [GU40768] courtesy of Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service), from a carbonised grain of oat. Bulk samples have been sent for processing and it is hoped that a second date from this material will confirm and improve on the accuracy of the first date. The floor of the kiln contained two substantial postholes and a third that was, apparently, unused at the time of the kiln’s destruction. This structural evidence may help in understanding how the kiln was used.

Trench extensions made to record more of the substantial eastern building, revealed in the previous year’s work, recorded a complicated series of stratigraphic relationships, indicative of a number of constructional phases. It is hoped that radiocarbon dating of bone from securely sealed deposits will provide dates for activity at this location.

The wall of the building appears to have cut through the floor of an earlier structure, and both appear to seal further underlying structural remains. The building itself, however, is bisected by a later wall built upon the latest

of the former floor surfaces. This later wall, conjecturally, may be the subsequent ‘barmkin’ wall depicted on an 18th-century estate plan. Fine carved masonry, reused in later constructional phases, indicates a number of high status buildings formerly standing in the immediate

vicinity.

A good range of late medieval pottery has been found along with a gold reliquary cross and a small copper-alloy buckle. The former has been identified by Penny Dransart (University of Lampeter) as relating to a tradition of ‘green’ crosses, symbolically reflecting the ‘living’ wood of the cross of the crucifiction. This particular example has bark-like modelling of its surface and stylised green foliage around the top. Its hollowed stem would have permitted the carrying of a holy relic, secured in place by a removable stopper at the base of the cross.

As ever, many thanks are owed to the landowner, Alex Forbes, both for his good-natured forbearance and for his wealth of local historical and Forbes family knowledge, to Aberdeenshire Council for their help in funding radiocarbon dates and sample analyses, and to AOC for their generous help and advice regarding sample collections.

Archive: Moray and Aberdeenshire Council SMR

Colin Shepherd – Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source: DES)

Excavation (July 2017 - October 2017)

NJ 5131 2642 A sixth season of work was undertaken, July – October 2017, at Druminnor Castle. The work included further interrogation of the rather complicated geological background of the site and continuing the examination of the E side of the former castle precinct. Also, results from

the environmental sampling of burnt deposits from the kiln (DES 17, 11) have contributed to a greatly enhanced picture of the local environment during the later 11th and 12th centuries at this end of Strathbogie.

A 15 x 2m trench exposed the underlying geology. NE to SW striking vary coloured sandstones and mudstones of Devonian Age, with a dip of c20° to the NW, have been intruded by a Late Carboniferous-Permian Age igneous

basalt dyke. The exposure of the northern contact between the two deposits displays a thermal metamorphic aureole, where the sediments have been baked, resulting in an obvious 0.2m wide cream coloured band adjacent to the basalt. The range of ‘naturals’ across the site has provided

much fun in determining archaeological from geological deposits, especially as redeposition of upcast material has been such a feature of the site’s development.

The ‘geological’ trench was also positioned in order to test whether the putative remains of an outer perimeter rampart may have existed along the line of a previously recorded stretch of wall (DES, 16, 11–12). This had been suggested as a potential entrance façade between earthen banks. The trench did appear to show the basal portions of what may have been a flattened rampart. It is hoped that the trench will be extended next year in order to confirm whether an apparent cut in the natural at the end of the

trench is, indeed, a quarry ditch for the suggested rampart.

At the E side of the site, the rather complicated stratigraphy has resulted in a slow progression of planning and section recording. The result is, however, a complicated but fascinating insight into a very busy architectural development of the site. It has become apparent that much

relating to the earliest recorded (thus far) four centuries of site use was quarried away, possibly in the mid-15th century, in order to provide a level platform on to which the main part of the castle, as visually-attested on 18th-century estate plans, was positioned. It is hoped that this timeframe can be confirmed by 14C analysis of bone and charcoal collected from stratified contexts. However, such analysis may well turn out to demonstrate that this platform-building phase may have begun earlier.

Subsequently, three superimposed buildings and a further possible enclosure wall were constructed over the quarry pits. These buildings were associated with a variety of floored surfaces including flagstones, mortared floors and beaten sand/earth surfaces. One fine drain associated

with laminated/renewed mortar floor surfaces suggests an interest in hygiene. Use of fine Correen stone for the drain indicates that a quarry on the Correen Hills was being utilised far earlier than is usually credited.

It would appear that Druminnor is demonstrating that Scottish castles of suggested 15th- or 16th-century date may well have deeper ancestries than anticipated. Also, that vast landscaping feats may well underlie many later ‘polite’ landscapes. It is unlikely that the complicated story being revealed at Druminnor is unique.

As ever, grateful thanks are owed to the landowner for his hospitality and historical knowledge of the Lords of Forbes and other families’ histories. Particular thanks are also owing to Aberdeenshire Council for their support in funding 14C dates, to The Hunter Archaeological and Historical

Trust for the environmental analysis and to AOC for their help and advice with sampling and species identification.

Archive: Moray and Aberdeenshire Council SMR

Funder: Hunter Archaeological and Historical Trust and Aberdeenshire Council

Colin Shepherd – Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source: DES, Volume 18)

Excavation (June 2018 - October 2018)

NJ 5131 2642 A seventh season of work was undertaken,

June – October 2018, at Druminnor Castle. This season has

helped to clarify the plan and chronological development of

buildings constructed in the lower court of the late 15th-/

early 16th-century castle enclosure.

Two structures were built against the inner side of the

N Barmkin wall with the NE corner of one forming the

corner of the castle complex as shown on an 18th-century

estate plan. The excavations appear to demonstrate the

reasonable accuracy of that plan. Radiocarbon dating has

provided a sequence of dates running from the second

quarter of the 15th century through to the middle of the

17th century.

The larger (western) building appears to be later than the

one in the corner and may have replaced an earlier structure

that would have been aligned with the corner of the smaller

building. The evidence for the destruction of the earlier

structure was sealed beneath two later floor surfaces and

overlay a probable third floor. The W wall of the smaller

(corner) building had been rebuilt after subsiding into an

underlying ‘ditch-like’ feature. The purpose of that feature is

still debatable (but, see below).

A receipt from 1440 for building works done on the

existing S range of the castle coincides with a closely dated

bone from on top of the natural in the area of the lower

court. This suggests the first half of the 15th century was

a period of massive reconfiguration at Druminnor. A royal

licence to build and fortify ‘Drymynour’ was granted in 1456,

along with the right to ‘circumvallate it with ditches’. The

lower court itself appears to have been added a couple of

generations later, perhaps around 1500.

In Trench 11, on another part of the site, earlier, tentative

suggestions of a possible ‘rampart’ appear to have been

unfounded. However, the feature that gave rise to that

speculation may perhaps be seen to have formed the

outermost deposit of a ‘terrace-like’ structure. This awaits

further corroboration next year. Most perplexing was the

recognition of a massive, rock-cut ‘cavity’ that had been

sealed by subsequent deposits, including the speculative

‘terrace’. However, it is still questionable whether this feature

is man-made or geological and further work needs to be

carried out to test those suggestions.

As ever, grateful thanks to Alex Forbes for permission to

continue work on his lawns and for his endless knowledge

of things ‘Forbes’. Also, many thanks to the volunteers

who tirelessly put their all into the quest for answers and

we are all grateful to Bruce Mann and Aberdeenshire

Council Archaeology Service for their enthusiastic support

of the project and for funding the radiocarbon dates. These

excavations form part of the Bennachie Landscapes Project,

jointly conceived and run by the Bailies of Bennachie and the

University of Aberdeen.

Archive: Aberdeenshire HER

Funder: Aberdeenshire Council for C14 dates

Colin Shepherd – Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source: DES, Volume 19)

Excavation (May 2019 - October 2019)

NJ 5131 2642 The eighth season of excavation at Druminnor Castle (NJ52NW 14) ran from May to October 2019. Findings from previous seasons are reported on separately (DES 2013, 15-16; DES 2014, 16-17; DES 2015, 11-12; DES 2016, 11-12; DES 2017, 11; DES 2018, 9-10) Approximately 2,500 square metres were covered encompassing most of the known footprint of the castle and its immediate gardens.

The survey revealed a range of features. Some could be readily associated with features shown on two 18th-century plans whilst others were completely unexpected. Amongst the unexpected was a shaft situated near the centre of the present car park. Excavation showed this to be a stone-lined well that had lain within the tower and been demolished in 1800. Finds from the well confirm this date as having been the time the well was in-filled. The tower may date to the second half of the 13th century and it is hoped that further excavation here may shed light on that early phase of the castle and confirm its period of construction.

Also unexpected was a collection of features lying within the 18th-century garden precinct but outside a length of substantial stone wall, previously excavated. All of these features were out of use by the time the estate plans were drawn. Excavation of a limited area has revealed two layers of metalled and cobbled surfaces, separated by a substantial layer of soil.

The geophysics revealed the line of the outer garden enclosure depicted on the estate plans. This lay at a depth of approximately 1.5m below present ground level and would have been difficult to locate without the GPR survey. Excavation shows this to have been a substantial wall of at least a metre wide that still survives in this section to a height of almost a metre. It is hoped that further work here will help to answer questions regarding the initial date of this boundary.

Trench 2 was due to be finalised this year but the last half metre brought further surprises. A section of trench, dated previously to AD 1425-1450, was shown to have cut through older archaeological features lurking in the very bottom-most corner of the trench. A planned extension to this trench should clarify the chronology and dating.

Archive: Aberdeenshire Council HER

Funder: Castle Studies Trust for GPR, Aberdeenshire Council for C-14 analysis

Colin Shepherd ̶ Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source DES Vol 20)

Excavation (2021)

NJ 5131 2642 The ongoing excavations at Druminnor continued after last year’s hiatus. This was the ninth season of work as part of the community-driven Bennachie Landscapes Project, organised by the Bailies of Bennachie and the University of Aberdeen. As has become usual at Druminnor, a limited excavation plan to answer a few outstanding questions rapidly suffered ‘project-creep’ as hitherto un-imagined remains surfaced!

Trench 13 investigated the remains, discovered by GPR, of the outer garden enclosure wall, visible on an 18th-century estate plan but destroyed soon after. The footings, buried by almost 2m of landscaping soil – indicate the wall was quite substantial.

The 18th-century plan also showed the entrance roadway to the castle at this time running a number of metres N of the wall. This anomalous position was considered to suggest the former existence of some feature, perhaps a ditch. This was indeed shown to have been the case, with the enclosure wall running hard against its southern edge. The two features together would have made a formidable defensive structure.

Trench 14 sought to define the platform believed to have underlain the original tower, thought to have been the earliest stone-built fortification on the site. GPR suggested where the southern edge of the platform might lie and this was duly proven during excavation. Quite unexpectedly, the remains of the stone- flagged entrance to the castle before the 1800 demolitions were also found to have survived intact after the removal of most of the upper courtyard at that time. Remarkably, these flagstones survived beneath the later Victorian mansion that was built on the site in the 1840s. Geological investigations are slowly teasing out the interfaces between the site’s geology, re-deposited geology, and archaeology – an arduous but essential task on this site. As a consequence of this and other careful re-examination, a wall foundation, formerly believed to have been associated with a later 16th-century remodelling phase, is now tentatively assigned to an earlier, perhaps late 12th or 13th-century, phase. This is based upon its relationship to a mid-12th-century kiln. Further walls sealed by the flagstones are still under examination.

Trench 15 was intended as a small intervention to confirm the geology of this part of the site and to try to find the termination of the early-15th-century defensive circuit. In reality, this turned out to be a much bigger task, as unexpected walls and a cobbled surface attested the survival of a completely unknown late-18th- century phase of re-organisation to the castle’s outbuildings and garden in this area. At time of writing, this work is still progressing with the original aims of the trench not even begun. Maybe next year!

As ever, grateful thanks to Alex Forbes for permitting us to ravage his grounds and for his bottomless vat of insightful historical and architectural advice and to the volunteers who, against all the odds, keep coming back year on year!

Archive: Aberdeenshire Council HER

Funder: C14 analysis funded by Aberdeenshire Council

Colin Shepherd – Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source: DES Vol 22)

Excavation (July 2022 - August 2022)

NJ 5153 2642 The summer of 2022 saw the tenth season of excavation at Druminnor and, as usual, simply added more confusion to an already-overcomplicated series of results. Druminnor has been nothing if not endlessly surprising!

The seemingly simple plan to uncover more of the 15th- century defensive ditch in order to find its terminus was scuppered by the unexpected discovery of a completely unimagined period of site landscaping spanning the period 1800 to 1840. This comprised a

wonderfully preserved cobbled surface, thought to be the floor of the family’s stables. These stables had been completely removed in 1840 when the site was given a further makeover during the construction of a new ‘mansion house’ abutting the surviving S range of the castle. Hot off the press news from the penultimate week of the dig is that the ditch does appear to continue, sealed by this cobbled surface, along with the surviving remains of a possibly 15th-century wall. Further confirmation will have to wait until 2023.

At the other, western, end of the former courtyard, the search for the walls of the former W range have proved largely abortive. However, we now have an excellent knowledge of 19th-century Victorian plumbing and sewerage! Sadly, because of the extensive pipework and associated trenches, much of the archaeology has been badly truncated. However, one very early wall appears to have survived sealed within a later wall of the W range of the castle that was, in turn, sealed within the subsequent 1840 mansion wall. No dating evidence was forthcoming. This was particularly unfortunate as other aspects of its construction and siting might make it a contender for being related to the 12th-century corn- drying kiln found previously. However, this has to remain in the realms of plausible conjecture.

Owing to the nature of the complicated geology at Druminnor, distinguishing between archaeological and redeposited geological deposits is not easy. Fortunately, the geological expertise of certain team members is usually able to arrive at a consensus (after a certain amount of good- humoured bickering) and we are achieving a good understanding of the Devonian period to complement our not-so-good understanding of the medieval. 400 million years we can do – 750 years, not so easy!

Joking aside, the excavations at Druminnor have certainly demonstrated the complexities lying behind the development of Druminnor Castle. The ability to spend years meticulously excavating – and sometimes re-excavating – a single site permits an in-depth understanding and the luxury to re-analyse assumptions and former conclusions. Most assumptions made during the first five y ears of excavation have b een c omprehensively u pdated by the subsequent five and, in many cases, former conclusions have been found to have been wrong. In other words, the Druminnor excavations are not simply investigating a particular castle site, but they are increasing our understanding of how we ‘do’ archaeology. As ever, grateful thanks to Alex Forbes for permitting us to ravage his grounds and for his bottomless vat of insightful historical and architectural advice. Also, many thanks to Mark Cockburn, a local farmer, who has very generously lent us his digger at no cost. Finally, so many thanks to the volunteers who, against all the

odds, keep coming back year on year!

Archive: Aberdeenshire HER (intended) Funder: Bennachie Landscapes Project

Colin Shepherd – Bennachie Landscapes Fieldwork Group

(Source DES Volume 23)

Field Visit

NJ 513 264 A programme of survey and recording was undertaken of the archaeology revealed in a series of trenches. These trenches had already been dug by the owner, with the intention of locating and assessing an extensive system of drains around the castle in the hope that these excavations would provide a solution to recent drainage problems that had been encountered. Initial site inspection showed that a wide range of archaeological features and deposits had been exposed.

Archive to be deposited in the NMRS.

Sponsor: Mr Alexander Forbes.

G Ewart and D Murray 2002