Burnswark, 'roman Siegeworks'

Temporary Camp(S) (Roman)

Site Name Burnswark, 'roman Siegeworks'

Classification Temporary Camp(S) (Roman)

Alternative Name(s) Burnswark, Roman Practice Camps

Canmore ID 72885

Site Number NY17NE 2.04

NGR NY 185 790

NGR Description NY 185 790 and 188 785

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/72885

- Council Dumfries And Galloway

- Parish Hoddom

- Former Region Dumfries And Galloway

- Former District Annandale And Eskdale

- Former County Dumfries-shire

NY17NE 2.04 185 790 and 188 785

(N camp 185 790; S camp 188 785). A large siege camp of 5.3ha lies on the S side of Burnswark Hill and a smaller camp of 3.2ha lies on the N side. In the NE corner of the S camp lies a fortlet dated to the Antonine period. These siege camps are likely to date from the middle or the second half of the second century.

S S Frere and J K St Joseph 1983.

Reference (1997)

NY17NE 2.04 185 790 and 188 785

Listed as Roman practice camps at NY 188 785 (South camp) and NY 185 790 (North camp), and burial-ground (possible).

RCAHMS 1997.

Publication Account (17 December 2011)

The flat-topped Burnswark Hill dominates the landscape of Annandale and across the Solway, and commands spectacular views from its summit. The hill is crowned by a hillfort and flanked by two earthwork camps and a presumed Roman fortlet, all of which were subject to a series of excavations in the 1890s (Barbour 1899) and then in the 1960s and 1970s ( Jobey 1978). The site has attracted considerable attention over the years since the 1720s, when Alexander Gordon recorded the two camps (1726: 16–17). This inspired a number of other antiquarians to visit (Christison 1899). The possibility that it was the site of a genuine siege gripped the imagination of many generations, although there was doubt about this for a number of years, with the preferred interpretation being that of practice siege works (Steer 1964: 24; Davies 1972). This notion gained more credibility following excavations by Jobey, who suggested that the occupation of the hillfort was abandoned long before the Roman invasion, with the defences severely denuded by the late 1st century ad (1978: 98–9), although just because the ramparts were no longer in use does not mean that the site did not continue to be occupied as an open settlement. An alleged line of circumvallation connects the two Roman camps, but many of these appear to be field walls and tracks, and two additional earthworks on the north-east and south-west side of the hill are now interpreted as prehistoric settlements (RCAHMS 1997: 179–82). More recently, plausible attempts have been made to reinstate the two camps as the site of a genuine siege (Campbell 2002; 2003; Davies 2006: 57–60; Keppie 2009; Hodgson 2009: 187 – see above, Chapter 2.2), with the alleged circumvallation not required. Various Roman weapons including spearheads, lead sling-bullets (glandes, recently interpreted as catapult ammunition, Rihll 2009), iron arrowheads and stone ballista balls have been found on the hill during the various excavations and fieldwork (Anderson 1899; Cormack 1959; Jobey 1978: 86–91). Roman finds broadly date from the 1st to the 2nd century AD (Jobey 1978: 82–96).

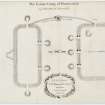

The camp on the north side of the hill is an unusual shape and gives the impression of two separate camps that have been joined. Collingwood felt that the camp had never been completed and that the layout reflected errors by the Roman army constructing the site (1927: 49–51). Certainly, an area of boggy ground on the north-west side has resulted in a gap, which may never have been fully built (contra Crawford 1939: 286), but alternative means of protection were probably employed. The camp measures about 296m from ENE to WSW by up to 112m in width and enclosed around 2.6ha (6.5 acres). Entrance gaps protected by tituli are visible on four sides, with an apparent reverse external clavicula also visible on the south-east side. The wide gap at the south-west entrance is probably the result of erosion by a nearby burn.

From the morphology of this camp, it is possible that it started life with a smaller square camp at its east side, which was subsequently extended, although St Joseph tested this theory by excavation and failed to locate any evidence (1952a: 98). Excavations recorded that the ditch was rockcut in places (Barbour 1899: 233). St Joseph’s excavations in the 1940s noted that the rampart comprised some 0.3m of clean red clay standing on two or three courses of turf (1952a: 98).

The south camp is equally unusual, although the earthwork is closer in form to the more usual rectangle. It measures about 260m from north-east to south-west by around 194m, enclosing almost 4.8ha (nearly 12 acres). There is a spring bisecting the camp, known locally as ‘Agricola’s Well’.

This camp overlies a presumed Roman fortlet situated in its northern corner, itself cut by later round-house platforms which appear to have partly utilised its perimeter (RCAHMS 1997: 181–2). Recent reassessment of the enclosure has postulated that it may not be a fortlet but relate to Iron Age occupation (H Welfare and S P Halliday pers comm). Detailed topographic survey of the enclosure and camp identified potential earlier features, and it has been suggested that some of these may indicate an earlier camp (Maxwell 1998a: 49).

The unusual element of this camp relates to its gates: while tituli are visible in the north-east, south-east and south-west sides (the latter not depicted on illus 92), the north-west side possesses three entrances protected with circular platforms (known as ‘The Three Brethren’). These measure some 3.5m high and are up to 15m across, and are frequently interpreted as ‘ballista platforms or ‘ballistaria’ (for example, see Maxwell 1998a: 46–9). Two of these were partially excavated by Barbour, who recorded that the mound of the central one was some 3.65m above the surface of the gateway and some 3.2m above the bottom of the ditch, which dips around 0.6m into the rock and is also partially stone-faced (1899: 227). The suggestion that these apparent enlarged tituli housed some form of artillery machinery was challenged by Campbell, who suggested that their enlargement was due to camp protection: the deflection of ‘heavy and destructive objects’ rolled towards the camp (2003: 29). However, he has since accepted the possibility that they are ‘ballistaria’.

Excavations in the north corner of the camp by the enclosure/fortlet recorded that the ditch was some 5.5m wide and 1.8m deep and cut through soft bedrock. The rampart was up to 1.5m high, with a number of stones acting as a kerb, suggesting that its width was 6.5m (Jobey 1978, 81). Earlier excavations had recorded that rampart and ditch were frequently’ lipped with stones’ , with the ditch some 3.6m wide and 2.7m deep, and the rampart 3.3m high (Barbour 1899: 224, fig 1). Barbour also recorded pavements in the gateways and camp interior, including the remains of a building in its centre (1899: 227–8). Later excavations by Jobey failed to locate this building, although an area of paving was noted (1978:82).

Barbour’s excavations implied a level of permanency in the occupation of this camp, or certainly prolonged occupancy, with paved roads and building debris, although because some of the latter could not be located by Jobey it is possible that some of Barbour’s findings may have been over-interpreted (Barbour 1899: 224–31; Jobey 1978: 79– 82).

The date of the occupation of the camps is unknown. It has been assumed that the enclosure/fortlet, if Roman, is Antonine in date, like many of the fortlets in south-west Scotland. If this were the correct interpretation, then the southern camp could relate to a practice siege, or an actual siege of the hill, possibly during the alleged troubles of ad 155–8 (Jobey 1978: 57; Hodgson 2009), during the campaigns of Ulpius Marcellus in the 180s (Frere and St Joseph 1983: 34) or perhaps even as late as Severus (Keppie 1989: 67). If an earlier camp pre-dated this postulated Antonine fortlet, then a Flavian occupation could be expected. But if the corner earthwork is an Iron Age enclosure rather than a Roman fortlet, then the date range is broader. Although the apparent clavicula on the north camp would favour a 1st-century date (see section 7b), its form is unlike all other claviculae in Scotland. Burnswark remains an enigmatic site.

R H Jones