Pricing Change

New pricing for orders of material from this site will come into place shortly. Charges for supply of digital images, digitisation on demand, prints and licensing will be altered.

Field Visit

Date 16 August 1913

Event ID 1089100

Category Recording

Type Field Visit

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/event/1089100

Tynninghame Church.

Fragmentary portions of the parish church of Tynninghame, which was dedicated to St. Baldred, lie within the policies of Tynninghame House, the seat of the Earl of Haddington, about a mile northeast of the village of Tynninghame.

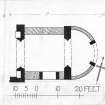

The structure had an unaisled nave and chancel, the latter terminating in an apse. The nave and the walls of the chancel and apse were demolished, leaving only the chancel arch, the archway to the apse and the two apsidal wall shafts (fig. 169). The apse was semicircular on plan and of the same width externally as the chancel (fig. 170).

A railing erected on the line of the walls encloses the ruin, which forms a burial place for the Haddington family.

The nave had an external width of 27 feet 10 inches; the eastern division between nave and chancel is 3 feet 9 inches thick. The chancel is 18 feet 3 inches long and is separated from the apse by a partition 3 feet 2 inches in thickness. These latter divisions have an external width of 24 feet 6 inches.

The archway between nave and chancel is 12 feet 3 inches wide. The jambs are recessed and have engaged shafts in the angles and on the jamb face. The bases, now covered, have rudimentary mouldings. The capitals are of the cushion type with rectangular abaci chamfered below; the surfaces of both capitals and abaci are enriched with imbrications.

The arch is in recessed orders, enriched on the soffit and sides of the inner order with the saw-tooth ornament; between this and the outer order, which also has the chevron enrichment, is a fillet ornament. The hood mould is invected, with continuous semicircular indentations on either edge.

On the west face of the archway there is, on either side of the arch, an arched recess 2 feet deep and 3 feet wide, which contained an altar. The northern recess is complete, and its archivolt is enriched with the chevron ornament.

The archway between apse and chancel is 11 feet 7 inches wide. The jamb section is similar to that of the chancel arch but smaller in scale. This arch also is in recessed orders. Over each shaft of the jamb the order is enriched with the saw-tooth ornament, the intermediate orders with the chevron. The hood-mould is enriched with a continuous series of opposed half-roundels. The capitals have palmette foliage voluted on the angle. The abaci are similar in section and contour to those of the outer arch but are enriched with the palmette leaf.

The wall shafts of the apse have intermediate bands enriched with the chevron. The capitals are scalloped and cubical. The abaci are elaborately surfaced with a lozenge motif. Although the remains of the church are scanty, the detail of the portions remaining are in a remarkable state of preservation and enable the date of the structure to be assigned to the 12th century. The spirit of the mouldings suggests a French influence.

TOMB RECESS.

Within the south wall of the chancel is a late 15th century tomb recess 6 feet 4 inches wide. The recess is arched equilaterally; on the archivolt are hollow and bowtell mouldings. At the apex of the arch are three escutcheons, of which that to the dexter is placed on a fret and bears a fess wreathed for Carmichael, presumably George Carmichael, rector of Tynninghame in 1475, who was appointed Bishop of Glasgow in 1482 but died before consecration. The central shield bears a star between three cinquefoils, which should be Hamilton of Belhaven. This would put it much later than that above, but the shield may have been originally blank, as the sinister one still is, and the coat added later. Within the recess is a worn female effigy, which apparently, however, has been transferred to this place.

GRAVE-SLAB.

Within the apse is a slab of red sandstone 3 feet long, 1 foot 9 ½ inches broad and 4 inches thick, on which is rudely incised a Latin cross; the arms, head and shaft have a breadth of 2 ½ to 3 inches. The arms terminate in crude fleur-de-lys.

HISTORICAL NOTE.

Tynninghame Church and lordship belonged to the (arch) bishops of St. Andrews, the latter having the status of a regality including the lands of Auldhame and of ‘Knowis Inche and Scowgall’ (1). But the earlier connection of the church was with Lindesfarne, to which ecclesiastical settlement belonged ‘all the land which pertains to the monastery of St. Baldred, and is called Tyningham, from Lammermoor even to Eskmouth’. The association with St. Cuthbert in the 7th century depends on the identification of ‘Tyningham’ with the Scottish not the English Tyne (2). At Tynninghame, however, Baldred - to whom the church was dedicated had led the life of an anchorite and died there in 756 or 757, Tyningham, too, being one of the three places in Lothian in which the saint is said to have been buried (3). In 941 Olaf Godfreyson ‘laid waste the church of St. Baldred and burned Tynninghame’ (4). From this date the history of the place is a blank till in 1094 ‘King Duncan’, son of Malcolm Canmore, granted to the monks of St. Cuthbert at Durham ‘Tiningeham, Aldeham, Scuchall (Scougall), Cnolle (Knowe), Hatherwick and all the service which bishop Fodanus had of Broceesmuthe’; but the authenticity of this charter has been called in question and, in any case, the grant never operated (5). ‘Fodanus’ is Fothad, bishop of St. Andrews 1059-1093, so that these lands apparently already pertained to that bishopric and remained with it. From. a reference in another case it is learned that the church had the privilege of sanctuary for ‘life and limb’ (6). From information supplied by the church records it can be inferred that the building originally extended to a length of from 70 to 80 feet, having one door. at the east end by which ‘the minister was used to enter’ and another under a tower at the west end. The church was structurally divided into four ‘rooms’ by the arch of the apse, the chancel arch and apparently another arch at the tower entrance. In 1665 the building was still ‘in good case,’ but after the union of the parish with that of Whitekirk in 1761 ‘the church was in great part pulled down and destroyed, the churchyard ploughed through, the gravestones taken away, the village itself improved’ (7), and so but a few fragments remain of what was probably the finest parochial example of Romanesque architecture in Scotland.

RCAHMS 1924, visited 16 August 1913.

(1) Reg. Mag. Sig. 1598 No. 688; 1618 No.1946; (2) Hist. de S.C. in Symeon of Dur. i.,199. cf. Introd. p. xvi.; (3) Symeon of Dur. Hist. Dunm. Eccles. i., p. 48; Scotichron. Lib. iii., cap. xxix.; (4) Symeon Hist. Reg. ii., p. 94; (5) Lawrie's Early Scottish Charters, No. xii.; (6) Liber de Calchou No. 21; (7) Waddell's Old Kirk Chronicle, pp. 27, 29, 33.

OS Map: vi. N.W.