The ecclesiastical area of Kildonnan descends in a series of terraces down to the modern farm to the south west. Sketches and early photographs show an open landscape, but this is not the case today.

Parts of the area are enclosed by a boundary wall, which can be seen to have been rebuilt several times over the centuries.

To the north of the area is a ruined church, believed to have been built by John of Moidart or his son Allan, 16th century chiefs of Clanranald.

In the burial ground that surrounds the church, it appears that burials were deliberately separated; Catholics were buried to the south of the church, and Protestants to the north of the "grave-yard" area, with space left between them.

The rectangular church itself is a building of mortared rubble, typical of the post-Reformation style. The west gable and side walls survive, but the east end has been largely destroyed. There is a single doorway in the south wall.

There is some debate as to whether the church was ever actually roofed, consecrated, and used as a place of worship.It was apparently roofless in 1625, when a visiting Franciscan missionary was asked to consecrate it and wrote of seeing it so. He was unable to perform a consecration however, and it subsequently became a burial ground. However, this is not to say that it did not once have a roof and was not being used regardless of consecration - it may simply not have been recorded.

As with many churches of this period, the interior was used for burial after the church fell out of use, and hence, the floor of the interior is significantly higher than the surrounding ground level, and covered with grave slabs.

There is a burial recess at the east end of the north wall, which contains two stone plaques, one of which bears a version of the Clanranald coat of arms, and the other the date 1641. Similar Clanranald shield armoury can be seen at Arisaig, Kilmory, and South Uist.

Several explanations have been put forward for the purpose and occupant of this burial recess. Local tradition dictates that it houses the remains of the celebrated piper Raghnall Mac Ailean Oig, but this is chronologically unlikely, as the inscribed date is around a hundred years before Raghnall's traditional birth-date of 1662.

However, similar recesses housing the remains of senior Clan Donald families have been found in churches across the Hebrides; as an offshoot of Clan Donald, it is not inconceivable that Clanranald families may have followed suit and buried their leaders in this way. Without excavation however, this remains a mystery.

Undoubtedly, some of the most interesting archaeological finds from Kildonnan are fragments of 6 medieval cross slabs. These date between the 7th and 14th centuries CE, and only one currently remains in the church - the other five can now be seen at the modern church in Laig. There is one cross slab however that is particularly interesting.

On one side is rendered a Christian cross; the other side however contains a representation of a hunting scene that is distinctly Pictish. Whilst one side is religious and the other secular, we don't know for certain if the sides are of the same date or of the same hand; however, the cross does appear to be slightly later, corresponding to a technique popular in the 9th century. This slab is also notable as being the only example of an inscribed carved stone in the Small Isles.

Also within the church is a strange carved statue that has been dubbed a "sheela-na-gig". It appears to depict a figure lying in state or sleep, with a curious pillow-shaped carving beneath its head, and its hands broken below the wrist.

It is difficult to argue that this statue is a true sheela-na-gig however. Sheela-na-gigs, found throughout Britain and Ireland, are apotropaic carvings of women exposing enlarged genitalia. Many theories exist as to what they represent, from Celtic fertility goddesses to representations of hideous and sinful female lust. The Kildonnan example has no defining gender qualities, and lacks the traditional genitalia, although this may be because it is broken below the hands. Far more likely however is that it is a fragment of tombstone from the 17th or 18th century.

Excavations in 2012 against the walls of the church did indicate that there were earlier stone buildings beneath, suggesting that there were structures that existed prior to the building of the church. In addition, a substantial building with mortared foundations was excavated in the burial ground. Both or either of these buildings are clearly earlier than the church and point to occupation prior to its construction, but as we cannot say for certain what date they are, we cannot conclusively link them with an earlier Christian settlement.

The presence of early Christianity in the area is however confirmed by the presence of the cross slabs, which date from a medieval time period, and unquestionably point to an established Christian community.

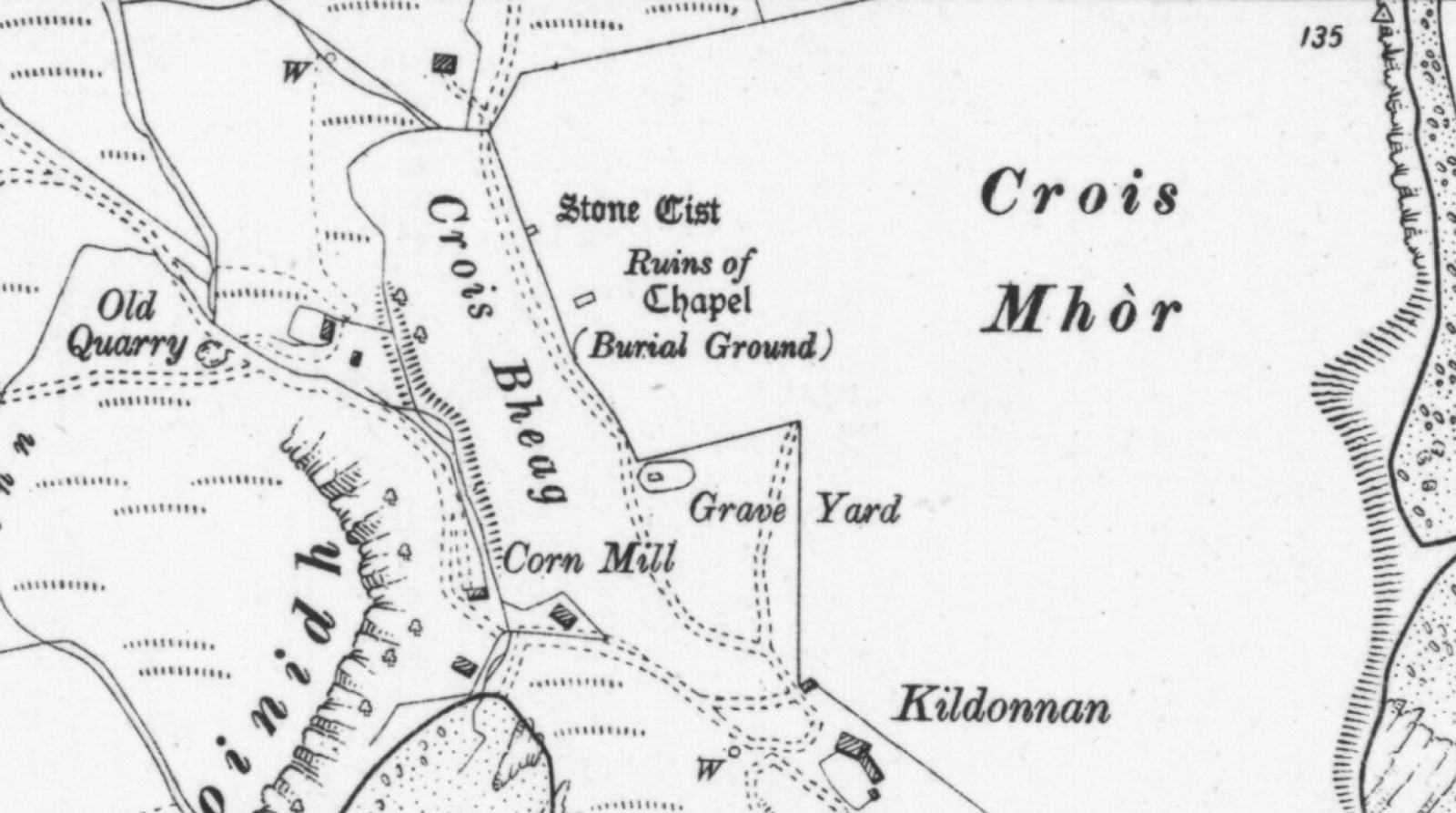

Furthermore, in addition to the dedication to St Donnan (Kildonnan means "Donnan's Chapel"), local placenames record the location of crosses - Crois Mhor ("Big Cross") and Crois Bheg ("Little Cross") - in this area.

Moreover, St Donnan's monastery on Eigg is recorded in a number of historical documents, which also detail his grisly fate. The Annals of Ulster for example records that the saint and his followers were massacred in the spring of 617 CE.

Whilst many versions of this story exist, all list the number of monks killed as over 50, which seemingly confirms that a substantial religious community was present on the island.

Finally,the death of a later Abbot of Kildonnan is recorded in 1725, which shows that the religious community in the area was re-established at some point; likely on the spot where it previously stood.

Unfortunately, little of the above can be substantiated; the archaeology of the area as yet provides no concrete information concerning a monastic settlement in the area. However, when studied together, what it can give us is a compelling sense of Kildonnan's use and re-use as a place of religious significance since the 7th century.