Dunstaffnage Castle

Castle (Medieval), Kiln (Period Unassigned), Midden (Period Unassigned), Structure (18th Century), Trench (13th Century)

Site Name Dunstaffnage Castle

Classification Castle (Medieval), Kiln (Period Unassigned), Midden (Period Unassigned), Structure (18th Century), Trench (13th Century)

Canmore ID 23036

Site Number NM83SE 2

NGR NM 88266 34491

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/23036

First 100 images shown. See the Collections panel (below) for a link to all digital images.

- Council Argyll And Bute

- Parish Kilmore And Kilbride

- Former Region Strathclyde

- Former District Argyll And Bute

- Former County Argyll

NM83SE 2 88266 34491

(NM 8826 3447) Dunstaffnage Castle (NR)

OS 1:10000 map (1976).

For adjacent chapel (NM 8808 3441) and marine research laboratory (NM 8810 3410), see NM83SE 3 and NM83SE 44 respectively.

For possible flint borer from Dunstaffnage Castle, see NM83SE 26.

For pier at NM 8833 3432, see NM83SE 45.

Dunstaffnage Castle occupies the summit of a prominent rock outcrop and is ideally placed to command the seaward approach to Loch Etive and the Pass of Brander as well as to exercise surveillance over the Firth of Lorn and the eastern entrance to the Sound of Mull.

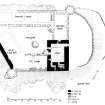

The castle incorporates the work of several building periods, ranging from the mid-13th century, the date of the original construction, to the early 19th century. Roughly quadrangular on plan, it measures about 35 meters SW-NE by 30 meters transversely over walls varying in thickness from 2.6 to 3.3 metres. There are circular towers at the north and west corners, while the gatehouse, consisting of two floors and a garret chamber, forms a massive frontal projection on the east side. The nature of the original entrance arrangements is uncertain, but is probably indicated by an arch-pointed recess in the east wall of the gatehouse at a height of 5.3 metres above ground-floor level, and which shows evidence of a drawbridge structure.

There were two distinct ranges of buildings within the area enclosed by the walls - the NW range and the east range. The most conspicuous surviving feature of the NW range is the dwelling house that was formed at the NE end in 1725. Formerly comprising two main storeys and an attic,it is now roofless and unfloored. It appears to have incorporated substantial remains of a late 16th century kitchen together with other remains of earlier date. The remaining portion of the NW range lying between the 18th century dwelling house and the West Tower has probably been roofless since the 18th century and the SE or inner wall has completely disappeared. The east range has almost completely disappeared.

The North Tower, much the larger of the two towers has an internal diameter of about 5.8 metres within walls 2.4 metres thick at first floor level. The size of this tower and its position in relation to the east range suggest that it probably contained the principal private apartments of the castellan, though there are no visible remains of fire- places or original chimneys within the tower, However, the tower has suffered considerable damage and remains to be excavated.

The West Tower, which comprised four storeys contained an unlit prison. Like the North Tower, there are now no traces of any fireplaces or chimney flues within the tower.

The rock-cut well serving the castle is situated immediately outside the NW range and has a modern superstructure.

Originally a stronghold of the MacDougalls, Dunstaffnage Castle came under the custodianship of the Campbells of Lorn in 1321 or 1322 following its capture by forces of Robert Bruce. Apart from a period in the late 14th and 15th centuries when it was held by Stewarts, it remained thereafter in the possession of the Campbells.

RCAHMS 1975, visited 1970.

As described.

Surveyed at 1:2500 scale.

Visited by OS (RD), 25 August 1971.

Excavation has partially revealed three openings, all subsequently blocked, piercing the inner face of the 13th century circular N tower, the S aperture perhaps being the tower's original entrance.

J H Lewis 1987.

The removal of c.2m of recent debris and a similar depth of medieval rubble and midden deposits exposed the base of the castle's 13th century N tower. The single surviving course of an E-W wall, built on bedrock below the tower's floor level, probably belonged to an early curtain rather than a partition wall.

Three apertures in the tower's internal wall face comprised: a window, sealed with coursed masonry, on the N side; a blocked opening that may have led into an intra-mural passage in the thickness of the E curtain wall; and, on the S side, a doorway leading into the E range. This doorway had been choked with rubble and other debris prior to the insertion of a 17th-18th century fireplace in the range's N gable.

J H Lewis 1988

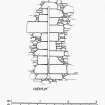

Excavation in 1987 and 1988 revealed three openings each blocked with masonry) piercing the inside face of the basement of the large, circular N tower (the donjon). On the N side was a window, sealed with coarsed rubble; on the E a doorway that may have led into a passage within the thickness of the E curtain; and, on the S, a doorway backing onto the fireplace in the n gable of the E range.

As an extension of this programme, excavation was renewed in 1989 with the aim of determining the relationships between the N tower and the E range, during the castle's early occupation and following its later modifications. This involved the removal of the 17th century to 18th century fireplace and the excavation below the hearth and within the northern half of the E range.

East Range

Within the 8.0m E-W by 7m N-S trench a thin layer of turf and topsoil overlay 0.30-1.3m of rubble, roofing slates, brick fragments, mortar, clay patches and dark humic soils, containing butchered mammal bones, pottery and glass fragments. The 19th century dates ascribed to many of the artefacts suggests that much of this debris was derived from the demolition of the castle's NW range which was occupied into the present century.

Although excavation is incomplete, three structural phases have been identified in this area.

Phase 1

The earliest structure in the NE corner of the range, comprised a few courses of a rubble-built wall (F211), faced with split boulders of schist. On the evidence of its alignment, F211 has been equated with the wall whose foundations were uncovered within the N tower (J Lewis, DES 1989) and which may have served as a temporary defence during the early years of the castle's construction. At some stage (probably still in the 13th century) the wall was demolished and replaced by the massive, extant E curtain.

Phase 2

The E range, measuring c12m by c6m, probably comprised a first-storey hall over a basement, whose function has yet to be determined but which probably conatined service accommodation.

In contrast to the building's E wall (the 6m high and 3m wide E curtain), the w wall survived only as 1.30m wide rubble foundations which petered out onto bedrock, c4.0m from the N tower. From this point the bedrock showed pronounced signs of wear for a distance of c1.20m, suggesting a basement-level entrance.

Further evidence of primary structures and occupation await future excavation.

Phase 3

At some stage the basement was sub-divided by a clay-bonded rubble partition wall (F206) which was partially exposed at the southern limit of the trench. A caly floor within the N chamber did not extend as far as the E or N walls, possibly because of 20th century attempts to expose and point the walls' masonry. Traces of probable occupational debris, overlying the floor, have yet to be investigated.

Fireplace.

The moulded-sandstone forepart and the brick base of the hearth were bedded onto the mortar, clay and sand which overlay mixed deposits of rubble and clay. Behind the back of the fireplace, mortared rubble sealed off the loose rubble and midden deposits that had infilled the N tower and which extended into the lower levels of the E range.

removal of these various structures and deposits revealed an ashlar-faced, dog-legged passage connecting the basements of the N tower and e range. The simple 13th century door jambs at the S end of the passage were overlain by the roll-moulded jambs of the 9possibly 18th century) fireplace, the latter masonry probably having come from other, dismantled castle buildings.

A narrow sondage, adjacent to the fireplace, revealed numerous deposits, including layers of sandy soil, rubble, clay, mortar and at least one more clay floor.

J Lewis 1989.

The fourth season of excavation within the castle was concentrated principally within a 3m-wide trench spanning the width of the bicameral E range, at its N end. The clay floor associated with the (now removed) 18th century fireplace had evidently been repaired on numerous occassions, as had an underlying mortar floor which was also of post-medieval date. Below were the remnants of several more clay floors which, on the evidence of the artefacts contained within the associated occupation deposits, were medieval in date.

Underlying the lowest floor surface were the remains of two substantial mortared walls and a robber trench. All of these features appeared to pre-date the e range and the adjacent N tower, both of which had been assumed previously to belong to the castle's primary mid-13th century phase.

In the S chamber rubble and midden material and an underlying layer of mortar, up to 0.40m deep and containing 19th century artefacts, overlay a spread of gravel that extended below the basement's ? 18th century partition wall. Removal of a modern wall at the S end of the room revealed the inside face of the building's ? primary gable. At the E end of the wall was an arched alcove, situated below the topmost step of a stair that may have given access to a first floor hall.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

J Lewis 1991.

Continuation of excavation at the S end of the castle's E range revealed the foundations of a stone stair, with its associated parapet wall, that had led to the first floor hall of the 13th century building and to a similar level in the adjacent 16th century gatehouse tower.

A single sandstone tread, 0.30m deep, survived at the base of the 1.70m-wide stair. The positions of some of the other treads was demonstrated by impressions within the mortar of the stair's foundations.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

J Lewis 1992.

Excavation, which began in 1987, of a ruinous intramural stair within the W wall of the castle's N (donjon) tower was completed by Scotia Archaeology Limited. The stair connected the first floor of the tower with its upper storeys; although there was no indication as to how access was gained from ground floor level. Extending 1.10m into the N wall of the tower was the socket for a large timber joist, one of the supports for the floor at first storey level.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

J Lewis 1994.

NM 882 344 An excavation was carried out in the basement of Dunstaffnage Castle in December 1999, to assess the deposits in this area prior to lowering the ground surface for visitor management purposes.

Two trenches were excavated: Trench 1 at the W end of the S wall and Trench 2 at the E end. The trenches were 0.8m and 1.1m deep respectively.

The deposit filling Trench 1 contained mortar chunks, slate fragments and stones. Sherds of transfer-printed white earthenware and stoneware jars, as well as bottle glass and some animal bones, were found within this deposit. The dateable material includes late 19th/early 20th-century material and possibly a few pieces dating to the 18th century. The W wall was not recorded in detail, but it was noted that it featured a blocked arch with a window being provided within this blocking.

The infill deposit seen in Trench 2 was basically the same as in Trench 1, and the finds were also similar in composition and date. There was a gun-loop or firing slot in the area above the W side of Trench 2.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

A Radley 2000

NM 882 344 Archaeological monitoring was undertaken in February 2004 during the excavation of a new soakaway for a septic tank 32m S of the visitor centre. The excavations revealed levelling materials, including ashlar blocks apparently originating from the castle fabric, but the specific architectural functions of which were not discernible.

Archive to be deposited in the NMRS.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

D Stewart 2004.

This site has only been partially upgraded for SCRAN. For full details, please consult the Architecture Catalogues for Argyll and Bute District.

March 1998

Dunstaffnage Castle.

Scottish Records Office:

The supply of building stone from quarries in Morven and agreement to undertake repairs.

Letter from James Duff (mason in Dunblane) to Patrick Campbell of Barcaldine.

1724 GD 170/834/1

Publication Account (1985)

This magnificent castle occupies the summit of an isolated rock stack at the head of Loch Etive, with the sheltered anchorage ofDunstaffuage Bay to the east. The castle was founded by the MacDougall family, Lords of Lorn, either Duncan MacDougall, who founded the priory of Ardchattan, or his son Ewen, and it dates in origin to the middle of the 13th century. The ground plan is largely determined by the quadrangular shape of the top of the rock stack; the walls are massive, rising from the conglomerate stack to form a castle of enclosure but with stout slightly projecting angle towers at the north and west corners and with an entrance tower at the east angle.Doubtless much of the accommodation within the castle would have been in stone and timber ranges against the curtain walls particularly on the northwest; rather grander accommodation, possibly including a first-floor hall, is implied by the architectural details of the east side, with the blocked windows of these rooms still visible from the outside. The castle was captured from the MacDougalls by Robert Bruce in 1309 and for some years it remained in royal hands. After several other holders in the 14th and 15th centuries the castle was, in 1470, granted to Colin, 1st Earl of Argyll; in 1502 the custody of the castle was vested by the then earl in his cousin, who became known as the Captain ofDunstaffnage. Today the castle belongs to the Duke of Argyll, with the hereditary Captain as the keeper of the castle with right of residence, though the guardianship of the castle is now vested in the Secretary of State for Scotland.

It is a measure of the success of the original concept that the castle has, except at the entrance tower, been so little altered. In the late 15th or early 16th century the entrance was re-arranged with the rebuilding of part of the east tower; access was across a wooden drawbridge at the head of angled steps leading from the base of the rock stack. The upper part of the gateway is probably oflate 16th century date. Further alterations continued till 1810 largely to improve the domestic arrangements of the north-west range and the gate-tower, though work to allow the greater use of firearms in the defence of the castle was also undertaken.

The chapel situated about 150m WSW of the castle was built in the second quarter of the 13th century, with the burial-aisle of the Campbells of Dunstaffnage continuing the line of building at the east end. The chapel is of simple rectangular plan, but the detail of the mouldings of the windows is of an intricacy and quality remarkable in the west of Scotland at this time. The three pairs of windows of the chancel have been the main areas of such decoration with dog-tooth ornament on the outside; the paired windows on the north and south sides of the chancel are particularly fine examples of Gothic embellishment. The architectural style of the chapel has been compared to contemporary work at the Nunnery on Iona (no. 43)and the parish church at Killean (no. 46).

Information from ‘Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: Argyll and the Western Isles’, (1985).

Excavation (1987)

Excavation has partially revealed three openings, all subsequently blocked, piercing the inner face of the 13th century circular N tower, the S aperture perhaps being the tower's original entrance.

J H Lewis 1987

Excavation (20 December 1999 - 21 December 1999)

An excavation was carried out in the basement of Dunstaffnage Castle in December 1999, to assess the deposits in this area prior to lowering the ground surface for visitor management purposes.

Two trenches were excavated: Trench 1 at the W end of the S wall and Trench 2 at the E end. The trenches were 0.8m and 1.1m deep respectively.

The deposit filling Trench 1 contained mortar chunks, slate fragments and stones. Sherds of transfer-printed white earthenware and stoneware jars, as well as bottle glass and some animal bones, were found within this deposit. The dateable material includes late 19th/early 20th-century material and possibly a few pieces dating to the 18th century. The W wall was not recorded in detail, but it was noted that it featured a blocked arch with a window being provided within this blocking.

The infill deposit seen in Trench 2 was basically the same as in Trench 1, and the finds were also similar in composition and date. There was a gun-loop or firing slot in the area above the W side of Trench 2.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

A Radley 2000

Kirkdale Archaeology

Watching Brief (16 February 2004 - 17 February 2004)

NM 882 344 Archaeological monitoring was undertaken in February 2004 during the excavation of a new soakaway for aseptic tank 32m S of the visitor centre. The excavations revealed levelling materials, including ashlar blocks apparently originating from the castle fabric, but the specific architectural functions of which were not discernible.

D Stewart 2004

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

Kirkdale Archaeology

Project (April 2007 - June 2007)

NM 8826 3449 In April and June 2007 a team of researchers drawn from the School of Environmental Science at the University of Ulster with support from the Queen's University of Belfast conducted an integrated landscape survey and assessment of the environs of Dunstaffnage Castle. The primary purpose of the survey was to undertake extensive terrestrial and marine topographic and geophysical survey of the landscape area of the castle with a view to reconstructing the formation processes of the headland and recording buried cultural remains. This project was carried out with both financial and logistical support of Historic Scotland which is gratefully acknowledged.

The Castle is located on an upthrown block of conglomerate whose NW vertical face lies along a NE trending fault line that can be traced along the edge of the conglomerate block, down to the shore along a topographic low (preferentially eroded along the fault plane) and onto Eilean Mor to the NE. Not only does the upthrown block of the fault lend an elevated position to the Castle, but the vertical face created by the fault plane also adds to the natural defences of the structure.

Geophysical survey was conducted both in the marine environment and on land. The geophysical survey of Dunstaffnage Bay and surrounding waters comprised an EdgeTech Model 272-TD dual-frequency digital side-scan sonar acquisition system and a high-resolution digital echo-sounder. Bathymetric data was contoured to produce 2- and 3-dimensional landscape models of the bay area and act as basemaps for further data presentation and interpretation. These data were combined with onshore topographic surveys to produce seamless digital terrain models depicting the coastal landscape. The side-scan sonar survey resulted in the production of seafloor maps outlining both sediment types and the potential presence and location of sites of archaeological potential. Unfortunately no cultural anomalies were detected on the seabed in the immediate vicinity of the castle. Data was ground-truthed by a combination of sediment

sampling exercises and diver-truthing.

Three primary forms of terrestrial geophysical survey were undertaken, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), Resistivity survey and Magnetometry. The magnetometry data is still being processed and its usefulness is under question due to the nature of the underlying geology. The GPR consisted of a series of transects running both north-south and east-west across the various survey areas. Resistivity survey was undertaken in three primary survey grids, with an attempt to cover as much of the available ground as possible. Both data sets were integrated and georeferenced with the topographic data obtained using a combination of total station survey coupled with GPS positioning.

The GPR survey carried out in the environs of Dunstaffanage castle indicated a ditch of varying size located close to the base of the bedrock. This feature was present at the SW, S, SE, NE and NW sides of the castle and is likely to be continuous around the structure. There is considerable variation in its appearance, being from 2-10m wide and 0.5-1.7m deep, and in one instance shows a hint that it may have been amended or re-cut. A number of visible surface features on the NE and SE sides of the castle were tested. These appeared as three subtle sub-rectangular features, sometimes evidenced only by vegetation change. These features were prominent in the resistivity survey. Two SE features were more promising and showed a strong consolidated reflection perhaps indicative of flooring or introduced material for a vegetable plot. To the SW a number of probable 'naust' features proved to be shallow.

The interior of the church showed no signs of burials, although there was shallow disturbance.

Finally, a number of topographic features were also identified including 1 Pond and associated channel features located directly N of chapel.

2 Two stone-built circular features with the appearance of hut/round house.

3 Series of level rectangular features located E and NE of castle. Quantities of post-medieval artefactual material contained in soil upcast in vicinity of these features.

4 Large level rectangular earthwork feature with second smaller feature directly to the S of castle.

5 Two, and possibly a third, earthwork features which have the appearance of boat nausts.

Funder: University of Ulster and Historic Scotland

Colin Breen, Wes Forsythe and Dan Rhodes, 2007.

Magnetometry (April 2007 - June 2007)

NM 8826 3449 In April and June 2007 a team of researchers drawn from the School of Environmental Science at the University of Ulster with support from the Queen's University of Belfast conducted a magnetometry survey of Dunstaffnage Castle.

Funder: University of Ulster and Historic Scotland.

Resistivity (April 2007 - June 2007)

NM 8826 3449 In April and June 2007 a team of researchers drawn from the School of Environmental Science at the University of Ulster with support from the Queen's University of Belfast conducted a resistivity survey of Dunstaffnage Castle.

Funder: University of Ulster and Historic Scotland.

Ground Penetrating Radar (April 2007 - June 2007)

NM 8826 3449 In April and June 2007 a team of researchers drawn from the School of Environmental Science at the University of Ulster with support from the Queen's University of Belfast conducted ground penetrating radar of Dunstaffnage Castle.

Funder: University of Ulster and Historic Scotland.

Excavation (June 2008)

NM 8826 3449 In 2007 an integrated landscape survey of the environs of Dunstaffnage Castle was undertaken. It included an extensive marine and terrestrial geophysical survey coupled with a conventional landscape survey. During this work a number of features came to light which warranted further investigation and in June 2008 limited test trenching was carried out across the site.

Trench 1 (2 x 2m) consisted largely of natural geological / geomorphological features and a number of planting features. Finds from this trench were modern and consisted of slate fragments and sherds.

Trench 2 (2 x 1m) was positioned in an apparently artificial hollow immediately above the raised beach area and had the potential appearance of a naust. Excavation revealed collapse from an 18th-century structure. A large volume of 18th- and early 19th-century material was recovered including a drinking glass stem, sherds, clay pipe stems and other assorted finds.

Trench 3 (2x1m) was positioned over a defined flat rectangular area NE of the visitor centre and E of the castle.

GPR survey appeared to show the survival of a floor surface at this location. Removal of the upper sod exposed a very thin spread of broken slate, brick and modern pottery. This had been spread out and levelled during 20th-century landscaping. This overlay a substantial soil deposit, 0.8m deep, consisting of well turned garden soil. A small number of modern finds came from this deposit.

Trench 4 (8 x 1m) was positioned to investigate a GPR anomaly that appeared to show a ditch surrounding the base of the castle outcrop. The trench was immediately below the southern castle façade and revealed a clear sequence of medieval and post-medieval activity. The earliest cultural levels took the form of a shallow trench surrounding the castle. This may have been associated with construction or may have been used as a temporary fence or slight defensive feature. Coin and artefact analysis would suggest a 13th-century date. Interestingly, the trench also produced evidence of significant refurbishment, possibly early in the 14th century. The analysis of a discarded brooch will allow closer dating of this event. Over the following 300 years this area was subject to continual dumping of midden material from the castle wall. The faunal material recovered will allow an accurate reconstruction of diet and economy from a sealed medieval context. This activity sort continued into the 18th century, when the site was finally abandoned and landscaped.

Trench 5 (2 x 1m) tested two enigmatic sub-circular stone features in the woodland NW of the castle. The structure was identified as a sub-circular stone walled kiln with a number of probable flues. The interior of the kiln contained a significant build-up of fill, with a substantial deposit of lime at the base. Unfortunately no dating evidence was recovered.

The excavations provided a valuable insight into the chronological sequence of activity at the castle and provided important information for developing future management plans.

Funder: Historic Scotland

Colin Breen and Wes Forsythe (Centre for Maritime Archaeology, University of Ulster), 2008

Watching Brief (16 November 2009 - 18 November 2009)

NM 8810 3410 An archaeological watching brief was undertaken in advance of development at Dunstaffnage Marine Research Facility on the outskirts of Dunstaffnage village. The area for development lay within an area of medieval activity and adjacent to two Scheduled monuments: Dunstaffnage Castle (NM83SE 2) and Dunstaffnage Castle Chapel (NM83SE 3).

No archaeological remains were encountered, although there were considerable remains mainly of concrete bases and brick foundations relating to the WW2 base that occupied the site prior to the Marine Research Facility. (GUARD 1126)

Sponsors: Dunstaffnage Developments Ltd, Davis Duncan Architects.

K Seretis 2002.

Excavation (27 July 2010 - 28 July 2010)

NM 8813 3422 A watching brief was undertaken on 28 July 2010 during the excavation of a trench for a new sign. The trench fill contained modern material which suggested that the area had probably been landscaped in the late 20 thcentury. There were no finds or features of archaeological significance.

G Ewart 2010

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

Kirkdale Archaeology

Audits (May 2014)

NM 88266 34491 An assessment of this collection in May 2014 established that four of the five pieces in the collection form the sides of an elaborately decorated font, and the fifth is a broken quern.

The four stones curve across their width and together form the panels from a font. The outer faces are worked with a series of trefoiled finials set between miniature gabled buttresses. The backs of the stones are curved to follow the curve of the outer face, and are roughly finished. The font panels are described and illustrated in John Lewis, ‘Dunstaffnage Castle, Argyll and Bute: excavations in the N tower and E range, 1987–94.’

This and other inventories of carved stones at Historic Scotland’s properties in care are held by Historic Scotland’s Collections Unit. For further information please contact hs.collections@scotland.gsi.gov.uk

Mary Markus - Archetype

(Source: DES)

Watching Brief (6 October 2015)

Under the terms of its PIC contract with Historic Environment Scotland, Kirkdale Archaeology was asked to carry out an archaeological watching brief at Dunstaffnage Castle during the removal of an existing sign (DSN021) in the castle courtyard, and the excavation of a shallow trench to install a new interpretation panel (DSN01) next to the ticket office in the castle grounds.

The excavations at the ticket office for DSN01 showed that the ground had been made-up relatively recently. This may be due to the re-direction of the path leading to the ticket office from the road to the castle. The current arrangement can be seen on the 6 inch : 1 mile Ordnance Survey map of 1959. This can be contrasted with the arrangement shown on the 1899 Ordnance Survey map (Fig. 3) where the path widens to the west of the ticket office. The re-arrangement of the paths here (probably during the early-to-mid-20th century) may account for the landscaping/make-up (103) encountered in Trench 1. Although nothing of particular archaeological interest was revealed during the works, the castle and its surroundings must be considered to be of high archaeological potential and any future ground-breaking work should be similarly accompanied by an archaeological watching brief.

G Ewart 2015

Sponsor: Historic Scotland

Kirkdale Archaeology

Watching Brief (21 September 2016)

A watching brief was maintained during the excavation of a trench to house a new sign indicating the direction of the disabled car park in the grounds of the castle. Although nothing of particular archaeological interest was uncovered, the installation of the sign has helped to establish the nature of a sequence of changes which have affected this particular area of the castle grounds since the mid-19th century. It again shows that the area immediately outwith the scheduled area still retains high archaeological potential.

Sponsor: HES

Paul Fox 2016

Kirkdale Archaeology

Watching Brief (February 2021)

NM 88287 34423 A watching brief was conducted during exploratory works for the replacement of a pipe and septic tank connected to the visitor centre of Dunstaffnage Castle (Canmore ID: 23026). Three test-pits were excavated to identify the line of the pipe between the visitor centre and a septic tank to the SE. Each test-pit identified that the pipe lay within topsoil backfilling the pipe trench. Screw augering to a depth of 0.6m indicated that topsoil was at least that deep and no other deposits were encountered. No archaeologically significant deposits or features were impacted upon.

Archive: NRHE (intended)

Oliver Rusk – CFA Archaeology Ltd

(Source: DES Vol 22)

Funder: Historic Environment Scotland

Ground Penetrating Radar (12 August 2022)

NM 88266 34491 A geophysical survey was undertaken at Dunstaffnage Castle on 12 August 2022. This survey forms part of a programme of investigations prior to replacement of a septic tank. Ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey was undertaken over a limited area to map buried utilities and depth to bedrock.

Two clearly defined services have been detected leading from the Visitors Centre toward the septic tank. One appears to be the pipe leading to the septic tank and is at a depth of approximately 0.40m. The function of the second response that lies 1m to the W at a depth of 0.45m, is unclear as it is unlikely, but not impossible, that two pipes lead to the septic tank unless one is a replacement. It is possible that the second response is a water pipe or a foul water drain associated with the known service that runs to the SE of the septic tank.

Due to the limited area available for survey the presumed service running SW to NE across the field, immediately to the SE of the current septic tank, has not been clearly identified. However, one linear response has been recorded which is likely to be associated with this utility.

The results suggest that this service crosses the track, in the S, in the area of the patched surface, but this too is ill defined due to the reinforced concrete and the patching.

A very well defined linear response has been recorded just to the S of the track and the response suggests a likely service but whether it is associated with the known service is unclear. However, both appear to be at least spatially associated with a rectangular response suggestive of a structure.

The GPR survey has not clearly defined the depth to bedrock. A clear surface has been noted beneath the main service but this is thought to be associated with the base of the pipe trench; it is not believed to indicate the bedrock interface as it is of limited extent. The data appears to suggest that the bedrock falls away at the SE with the made ground/imported soil resulting in a weaker response.

Archive: Rose Geophysical Consultants Funder: Historic Environment Scotland

Susan Ovenden – Rose Geophysical Consultants

(Source: DES Volume 23)

Mortar Analysis

NM 88266 34491 A programme of landscape, buildings and

materials analysis is being carried out at Dunstaffnage Castle

within the framework of this project Buildings analysis at

Dunstaffnage Castle has focused on the N and W towers, and

SE curtain wall of the upstanding castle. Interpretation of the

character and stratigraphy of constructional fabric at the site

is often limited by widespread consolidation, but several areas

are visible, and a variety of phase-specific masonry styles,

sandstone sources, and mortar compositions are in evidence.

A programme of materials sampling has been undertaken.

Archive: NRHE (intended)

Funder: University of Stirling and Historic Environment Scotland

Mark Thacker – University of Stirling

(Source: DES, Volume 19)

Archaeological Evaluation

NM 88266 34491 Previous analysis (DES 2018, 44) has been continued for another year. This season’s work included closer investigation and characterisation of the NW Range, E Range and SW Curtain masonry fabric, and the sample assemblage was increased accordingly.

On-site and lab-based analyses have revealed that a range of phase-specific stone emplacement techniques, mortar compositions and stone types pertain at Dunstaffnage Castle. These materials are subject to continuing investigation through a programme of thin section petrographic, archaeobotanical and radiocarbon analyses.

Archive: NRHE (intended)

Funder: Historic Environment Scotland and University of Stirling

Mark Thacker - University of Stirling

(Source: DES Vol 20)