Scheduled Maintenance

Please be advised that this website will undergo scheduled maintenance on the following dates: •

Tuesday 3rd December 11:00-15:00

During these times, some services may be temporarily unavailable. We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause.

South Uist, Kilpheder, Bruthach An Tionail Ard

Aisled Roundhouse (Iron Age), Midden(S) (Period Unassigned), Brooch (Bronze)(Middle Iron Age)

Site Name South Uist, Kilpheder, Bruthach An Tionail Ard

Classification Aisled Roundhouse (Iron Age), Midden(S) (Period Unassigned), Brooch (Bronze)(Middle Iron Age)

Alternative Name(s) Rubha Ardoch; Bruthach A' Sithean; Bruthach Sitheanach; Bruthach An Tioanail; Bruthach An Tirrail; Aird

Canmore ID 9855

Site Number NF72SW 1

NGR NF 7326 2020

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/9855

- Council Western Isles

- Parish South Uist

- Former Region Western Isles Islands Area

- Former District Western Isles

- Former County Inverness-shire

NF72SW 1 7337 2022

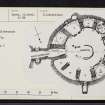

(NF 7337 2022) Wheelhouse Bruthach Sitheanach

OS 6" map, annotated by A L F Rivet (Assistant Archaeology Officer)

At Kilpheder, South Uist, on a site called Bruthach a' Sithean or Bruthach Sitheanach, (the Brae of the Fairy Hill), a well-preserved aisled wheel-house was excavated by Lethbridge in 1951-2.

Objects found include pottery, bronze and iron pins, etc. An R.B. trumpet brooch, dated by R G Collingwood to the mid-2nd c. AD., was probably left behind on a ledge about 200 AD. (a date deduced by Lethbridge) when the building was abandoned.

Connected with the site are middens 150 yards and 350 yards south-west and 200 yards south-east (See NF71NW 10 & 11) One yielded a long-handled weaving comb.

The finds were donated to the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland (NMAS).

T C Lethbridge 1952; Proc Soc Antiq Scot 1961; R W Feachem 1963.

(Area NF 732 202) Group of several wheelhouses, (one partly excavated 1951), extensive middens etc.

(undated) information from R W Feachem.

The remains of this aisled round-house are as planned and illustrated by Lethbridge, although several of the stone piers have collapsed. The walls stand to an average height of 2.4m. The hearth can just be discerned as a few stones protruding from the turf.

Surveyed at 1:2500.

No trace was found of the middens associated with the site or of other wheelhouses in the area.

Visited by OS (W D J), 6 May 1965.

The trumpet brooch is Roman, late 2nd century AD.

A S Robertson 1970.

NF 733 336-NF 758 140 Almost half of the South Uist machair has been surveyed between 1993 and 1995, in a single stretch from West Kilbride in the extreme S of the island to the N of the Ard Michael promontory, a distance of 20km with the width of the machair averaging about 1km (see unpublished reports, Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield). Existing RCAHMS records for prehistoric and early historic settlement sites number some 20 locations within this zone. The machair project has now increased this number to 81. Two of the RCAHMS sites, the broch/dun at Orosay (NF71NW 5) and the broch of Dun Ruaidh (NF72SW 7), are misidentifications.

The area most responsive to field survey on the machair is the section between Kildonan and Stoneybridge, the N 5km portion of the survey area. Here, where most of the surviving machair plain has not been covered by dunes, some 44 sites have been recognised. along with a grouping of Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age settlement mounds in the Kildonan area, the main settlement pattern is a set of clusters of Iron Age to Viking Age settlement mounds for each of the five townships. These Iron Age-Viking Age clusters may be viewed as predecessors to the township system first mapped in 1805 and still in use today.

A second concentration of sites has been found further S in the machair of Daliburgh and Kilpheder, where a total of 19 sites have been discovered in an area of 3 square kilometres. This density is all the more remarkable given the large extent of dune incursion on to the machair plain in this area. Within this zone two key house sites, both well preserved, have been excavated. One is Kilpheder wheelhouse (NF 7337 2022) of Middle Iron Age date and the other is the Cladh Hallan double roundhouse (NF72SW 17) of Late Bronze Age date. The most remarkable feature of prehistoric settlement in this area is the 500m long string of Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age settlement W of the modern cemetery. However, there is considerable potential for good preservation, as indicated by the 1994-95 excavations.

The results of the recent survey are by no means exhaustive but they do indicate a remarkable density of later prehistoric and early historic settlements on the machair. The pattern of proto-townships throughout the survey area holds reasonably well but there are gaps for the townships of Garrynamonie and Garryheillie.

Sponsor: Historic Scotland.

M Parker Pearson 1995.

NF 764 474 to NF 758 140 The South Uist machair has been surveyed between 1993-1996, from Cille Bhrighde (West Kilbride) in the extreme S of the island to Baile Gharbhaidh (Balgarva) at the N end of the island, a distance of 35km. This year, the number of known prehistoric and Early Historic settlement sites has now increased from 81 to 176.

The continuing pattern of Iron Age-Viking Age settlement clusters along the machair supports the hypothesis of 'proto-townships'; that the system of land allotment amongst the townships is essentially an Iron Age phenomenon which survived substantially intact until the Clearances of the early 19th century (see unpublished reports, Sheffield University). An unusual concentration of sites was found at Machair Mheadhanach in the Iochdar (Eochar) area, N of the rocket range and W of Loch Bee; some 35 settlement sites, ranging in date from the Late Bronze Age to the early post-medieval period, are strung out within a 2km line along a NW-SE axis. This multifocal pattern is very different from other settlement patterns on South Uist but still fits the 'proto-township' model.

The second major concentration of sites is at Drimore where a group of 14 settlement sites, of various dates, are arranged in a SSE-NNW line 750m long. Most of these were identified in the 1950s during survey and excavation in advance of the construction of the rocket range.

The pattern of hypothesised proto-townships throughout the survey area (unpublished report, Sheffield University) holds reasonably well but there are gaps for each of the six 'shieling' (gearraidh) townships of South Uist. This suggests that these shieling townships may have formed in the medieval period by sub-division of larger units, and thus do not have prehistoric predecessors. Other medieval peatland settlements are tentatively identified at Upper Bornish, Aisgernis (Askernish), Frobost and Cille Pheadair (Kilpheder). There is a strong possibility that most of the nucleated villages mapped by William Bald in 1805 are located on earlier post-medieval and medieval settlements. The movement of settlement off the machair mainly occurred in the post-Norse medieval period. The only exceptions are Baghasdal, where the machair settlement was abandoned only after 1805 supposedly due to 'machair fever' (James MacDonald pers comm), and Machair Mheadhanach which was deserted some time between 1654 and 1805.

Sponsor: Sheffield University.

M Parker Pearson 1996

Resistivity (1998)

NF 73 20 The two Middle Iron Age settlement mounds (Sites 64 and 63) on Cille Pheadair machair have been recorded since 1950. Site 64 is the location of the wheelhouse excavated by T C Lethbridge (NMRS NF 72 SW 3). Geophysical survey, using a resistivity meter, on both mounds has identified anomalies which suggest the presence of two more undisturbed wheelhouses in Site 64 and a potential group of other wheelhouses in Site 63.

A Chamberlain and M Parker Pearson 1998.

Publication Account (2007)

NF72 3 KILPHEDIR ('Bruthach Sith-eanach', 'Bruthach a' Sithan', 'Bruthach an Tional Ard', ‘Cille Pheadhair’) ++

NF/7337 2022

This probably dug-out aisled wheelhouse near Kilpheder in South Uist was excavated by T C Lethbridge in 1951-52; the Gaelic name means 'Brae of the Fairy Hill', the 'hill' being the mound before excavation. The site is near the southern end of the west coast of the island on the machair (grass-covered dunes) not far from the beach. When the author saw the site in 1974 it was not much more than a crater in the sand containing a scatter of large stones. Lethbridge undertook the work in order to encourage the local people to take an interest in their antiquities [2, 176]. The site was not recorded by the Commission (RCAHMS 1928).

1. The excavations

Excavation showed that there was a circular stone roundhouse buried in the sand but it is still not clear how thick the wall was; Lethbridge thought that it had an earth-cored wall with a stone outer face but his plan implies that the thickness was not established anywhere except at the entrance which may in fact have been a lintelled and stone-lined passage in the sand. Dug-out wheelhouses had not been properly recognised at the time and Kilpheder is likely to have been one of these – namely a deep circular pit in the sand the sides of which were lined with a single facing of stones. The 1956 rocket range excavations clearly identified such dwellings for the first time (for example NF74 2). The fact that midden material was found on top of the main wall tends to support this idea.

The excavator thought that the roundhouse was probably the centre of a complex of buildings but none of these were found or explored. He also supposed that there was an old, buried machair surface on which the house had been built [2, fig. 1, section] but this seems unlikely if it was inside a pit in the sand.

The building: the internal diameter at ground level was 7.93m (26 ft) and the wallface still stood up to about 2.75m (9 ft) throughout much of its circum-ference [2, pl. XIX). A series of eleven radial stone piers – varying in length from 1.37 - 1.98m (4.5 - 6.5 ft) – projected from the wall into the interior leaving a clear central space 5.49m (18 ft) in diameter. The piers thus formed ten open-fronted cells around the wall, the eleventh being formed by an inward extension of the sides of the entrance, slightly widened at its inner end. Nine of the piers were free-standing for the first 1.22m (4 ft) of their height, leaving an outer passage, or aisle, 38cm (1 ft 3 in) or more wide. A pair of heavy lintels roofed the aisle in each pier and the masonry of the piers continued up above these, bonded to the outer wall. More than one of these lintels had evidently cracked while the house was in use and the spaces under these were blocked with stone-work.

The piers were about 46cm (1 ft 6 in) wide at their bases but widened as they rose to a height of, in one case 2.44m (8 ft). The excavator considered that this widening meant that the piers had once curved over to form a stone dome over each of the ten bays. A similar arrangement can be seen in two of the roundhouses at Jarlshof (HU30 1), though the bay roofs of these are formed of flat stone slabs which cover the top of the corbelling. No fallen rubble was found on the floor at Kilpheder so it seems that the house was abandoned intact and that the upper parts of the piers were robbed after the whole had been filled with sand. The discovery of a complete enamel bronze fibula and other useful objects on the stone shelves in the outer wall (below) tends to confirm the abandonment theory.

Not only were the sides of the piers thicker as they rose but the inner ends too formed a shallow, inward curve [2, fig. 3]. The excavator considered that these faces had been dressed in situ by pounding to create an even curve. The tops of these inner faces had curved inwards about 15cm from the bases at a height of 2.4m. He suggested that the piers were so designed to hold a large round leather tent which filled the whole interior. It seems more likely now however that a thatched roof covered the central zone and the inwardly curved piers were designed to reduce the distance to be spanned by the wooden rafters.

The entrance passage was 4.42m (14 ft 6 in) in length and was equipped with door-checks; from the plan the door-frame appears to be very close to the inner end. A pair of opposed raised aumbries or cupboards, each lintelled, was near the outer end. Just within the door-frame were two radial piers, bonded to the outer wall, which formed a kind of inner vestibule for the passage. Traces of clay luting in the masonry were observed.

In the centre of the building was a large horseshoe- or U-shaped hearth resting on the sand floor with its open end facing the entrance; its floor was formed of baked clay and the kerb was a row of large beach pebbles. It measured 1.68m (5 ft 6 in) wide at the open end and was 1.24m (4 ft 1 in) long. Little occupation debris was found in the central area of the house, suggesting that this was frequently swept out. No other floor level features were reported.

The entrance to a long passage or store-room was found at ground level in Bay 5 but this was not explored; it was doubtless a souterrain reached from inside the roundhousen, of the kind since noted in several other wheelhouses. Other bays had open-fronted cupboards or aumbries in their back walls which obviously served as shelves [2, fig. 3]. The uses of some of the bays themselves could be inferred from the debris on their floors. For example in no. 4 were the remains of a stack of peats, apparently cut with the shoulder blade of a red deer. The aumbry in Bay 3 contained a quartzite pebble strike-a-light, a piece of pumice, a bone awl and a bone ferrule. For some reason this bay was thought to have been used as a latrine. Another aumbry in the same bay contained another strike-a-light and a Romano-British bronze brooch.

There is a possibility that pits existed in the sand floor of the wheel-house – like those at Sollas (NF87 5) – but Lethbridge does not seem to have systematically explored below floor level in the central area. In some of the bays he reported "hollows in the sandy floor so that the occupants could sit and work in comfort..." He makes no mention of finding anything in these.

2. Discussion

The building. Until the excavation of the Cnip roundhouses in Harris (NB03 2), Kilpheder was the best preserved example of what one might call the 'Jarlshof type' (as opposed to the 'Clettraval type' – NF77 2) in which the tall radial piers widen as they rise and appear designed to form a complete stone roof over each bay (though not, one suspects, over the central area). It is also of considerable interest, first, because of the high-status finds from it (below) and, second, because of the straightforward nature of the other finds and of the internal design. There is no real reason to doubt that Kilpheder was an inhabited roundhouse farm; there seem to have been no traces of the strange features – inevitably termed 'ritual' – which have been found in other comparable sites. Still less does it look like any kind of temple, Roman-inspired or otherwise [9].

Since Kilpheder was a dug-out structure rather than an above-ground roundhouse (like NF60 8 and NF77 2) any of the accompanying structures which one would expect if the main building was the focus of an Iron Age farm would presumably also have been sunk in the sand and therefore difficult to locate. Whereas at Clettraval (NF77 2) and Tigh Talamhanta (NF60 8) the whole layout of each farm, including its boundary wall, could be identified, any such features at the dug-out structures are unknown. It would be easy to conclude therefore that the dug-out roundhouses are a different type of structure – perhaps not farms at all [9] – but this would be a rash conclusion in the absence of proof that subsidiary farm buildings did not accompany this group. Thorough excavations around the main building have not been carried out at any of the dug-out structures so such proof or disproof is not yet available.

3. Material culture

Most of the pottery seems to have been elaborately decorated versions of the small cordoned vases found at Balevullin on Tiree (NL94 2) in a probable pre-broch context and therefore known as Balevullin vases (MacKie 1963) (Illus. 8.209). The Everted Rim ware characteristic of the broch builders on Tiree (but not elsewhere – see NF72 1) seems not to have been present. In this way Kilpheder is similar to other Outer Hebridean and Skye sites in that the builders and occupants used the 'native' Vaul ware and not the new Everted Rim ware with its possible exotic elements. The absence of the latter from Kilpheder implies that the roundhouse had been abandoned by about AD 300 at the latest.

Most of the decorated pottery found in the bays came from the lowest part of the occupation layer, which was about 30cm thick with no recognizable stratification [2, 189]. No ceramic sequence could be observed except in Bay 5; here there were two occupation deposits separated by a thin layer of blown sand. The lower layer had the decorated sherds while the upper contained only plain ware. One might suppose that the latter represents a late Iron Age occupation of not before the 7th century but – although bone pins of this late period were found nearby (NF72 5) – none occurred at Kilpheder.

The group of middle Iron Age settlements in this part of south Uist also seems to be unusual in yielding a series of rare metal pins and one Romano-British brooch. With one exception (site NF74 2) none of the 'rocket range' roundhouses in northern South Uist and Benbecula – excavated in 1956 – produced such exotic material. Indeed Roman material of all kinds is almost non-existent in the Outer Hebrides so that to find two signs of it at Kilpheder is quite remarkable. The enamelled 'trumpet brooch' is extremely rare in the north [5] and the use of lead for welding iron into a socket (as in the bone handle) is a distinctively Roman practice, seen for example on army querns; lead does not seem to have been known in Scotland before the Roman army arrived in about AD 79. A lead spindle whorl was found at Dun Mor Vaul (NM04 4) and large quantities were found at Leckie in Stirlingshire (NS69 3) where there was abundant evidence of Roman contact.

It is difficult not to conclude that these more southerly roundhouses in the Outer Isles were lived in by higher-status families with contacts with the south Scottish mainland. Even stranger is the fact that the nearby broch Dun Vulan – which one would expect to have been at the apex of local middle Iron Age society – appears not to have had any exotic luxury material during most of its long history (NF72 1).

The pottery found is discussed in the next Section.

4. The finds

No contexts are given for most of the finds.

Iron objects included part of 1 ring-headed pin of northern type [2, fig. 4.2], and presumably a knife blade in the horn handle mentioned under 'lead'.

Bronze objects included 1 enamelled brooch with a trumpet terminal [2, fig. 4.1] similar to the one found at Leckie (NS69 3) and also at the late 1st century Roman site at Newstead [5]; it was an old brooch when finally abandoned in the roundhouse and the catch plate had worn down and been replaced with one riveted on.

Lead: traces of this metal were found in the socket of a horn handle [2, fig. 6.4] and had presumably welded in the iron blade.

Bone and antler: many artifacts were found including a simple awl or pin formed from a bone splinter [2, fig. 4.7], many simple awls [2, fig. 4, nos. 9 and 13], 1 needle of standard Iron Age type with a pointed butt [4, fig. 4.5], several handles or hafts formed from sawn-off pieces of antler tine (the one with lead in its socket may have been a sickle handle), 1 possible long-handled comb with the teeth broken off [2, fig. 4.10], 1 mallet made from a small whale vertebra, 2 picks made from antler tines, one with part of the shaft-hole preserved, 2 small flat spoons [2, fig. 4, nos. 3 and 4] (resembling a similar notched object from Dun Mor Vaul which was probably for net making – Illus. 8.000), 2 potting tools, one with a zig-zag incised ornament [2, fig. 4.6], 2 socketed ferrules, perhaps ox goads [2, fig. 4 nos. 11 and 12], 1 rib knife [2, fig. 4.8], 1 shovel formed from a deer scapula, and various worked fragments.

Stone objects include many pebble hammerstones, slate pot-lids, and fragments of 2 lower stones of rotary querns, both used as building stones in the roundhouse.

The pottery included many small sherds found in the upper parts of the floor deposits in the bays which had evidently been trampled in by the inhabitants; only in Bay 5 could a stratified sequence be observed in the form of two occupation layers separated by layer of white sand from 2.5 to 5cm thick, but here the sherds in the upper level were from plain pots. Most of the decorated pottery evidently came from the clear primary occupation layers in the bays, usually about 30cm (12 in) thick, which rested on the basal sand and which showed no internal stratification [2, fig. 7]. One rim of a Vaul ware vase is illustrated [2, fig. 7.2] and one Vaul ware urn rim sherd has an unusual incised pattern showing a pair of stags [2, fig. 9, left: 3].

Since it has been clearly established at Dun Vulan that Everted Rim ware did not arrive at that high-status site until about the 2nd century at the earliest (NF72 1) (in sharp contrast with the situation at Dun Mor Vaul), it appears that its absence on many neighbouring wheelhouse sites – including Kilpheder – either means that the entire occupation of these took place before that date or that Everted Rim ware was not available to the inhabitants of all these roundhouses. However the fact that Kilpheder produced a fine Romano-British brooch indicates that the absence of Everted Rim ware here was probably not due to an absence of social status; the chronological explanation therefore seems preferable.

The incised sherd with a drawing of two stags on it is worth noting; a similar stag was found on pottery from Coll [2, fig. 9] and a possibly similar animal-decorated piece comes from Dun Mor Vaul (MacKie 1974, fig. 19, no. 471). Thomas has discussed the first two items [3]. It is tempting to see a connection between the stag images and the old Celtic horn-headed god Cernunnos.

Sources: 1. NMRS site no. NF 72 SW 1: 2: Lethbridge 1952: 3. Thomas 1963, 15 and fig.: 4. Feachem 1963, 98-99: 5. Bateson 1981, 29-30 6. MacGregor 1976, 9, 153, 155-6, no. 331: 7. Armit 1992, 65-6: 8. Crawford 2002, 114, 117-18, 121, 123-4: 9. Armit 1996, 137, 143, 147, 150, 155-6, 161 and 180: 10. Armit 2003, 136: 11. Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 1995 110, Ibid. 1996, 110, Ibid. 1998, 102: 12. Hunter 2002, 131, 134: 13. Proc Soc Antiq Scot 92 (1958-59), 120 (donations): 14. Robertson, 1970, Table 4: 15. Sharples 2003, 151-52.

E W MacKie 2007