Burghead

Floor(S) (9th Century), Fort (Iron Age), Midden (9th Century), Post Hole(S), Structure (Post Medieval), Bead (Roman), Coin (Roman)

Site Name Burghead

Classification Floor(S) (9th Century), Fort (Iron Age), Midden (9th Century), Post Hole(S), Structure (Post Medieval), Bead (Roman), Coin (Roman)

Alternative Name(s) Burghead, Promontory Fort; The Clavie

Canmore ID 16146

Site Number NJ16NW 1

NGR NJ 1090 6914

Datum OSGB36 - NGR

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/site/16146

- Council Moray

- Parish Duffus

- Former Region Grampian

- Former District Moray

- Former County Morayshire

Burghead

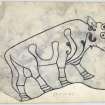

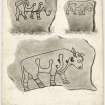

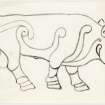

The Morayshire promontory of Burghead was the location of a great Pictish fort, and the surviving sculpture implies that it had its own church and burial ground. The earliest are six blocks of stone each incised with a powerful image of a bull (nos 1-6), which are associated with the fort itself, as may be the ‘celtic head’ said to have been found in the great well in the lower enclosure of the fort. Sadly the sculpture to be associated with the church is a very fragmentary glimpse of what must have been an impressive collection of cross-slabs and at least one shrine-chest.

A Ritchie 2019

NJ16NW 1 1090 6914

(NJ 109 691) Fort (NR)

OS 6" map, (1959)

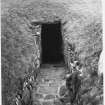

For well at NJ 1102 6915, see NJ16NW 2.

For coastguard station, rescue equipment store, lookout point and storm signal within the area of the fort, see NJ16NW 88.00 (NJ 1083 6913) and NJ16NW 88.01 (NJ 1084 6917).

The mutilated remains of a massive promontory fort, possibly dating from the 4th to 7th century AD, which was practically destroyed by early 19th century 'improvements'.

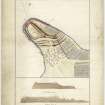

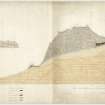

As planned by Roy in the mid-18th century the fort consisted of three ramparts with ditches, cutting off the headland of Burghead, on which lay a bisected, walled enclosure the larger of whose 'courts' on the NNE lay at a lower level than the other.

The cross-ramparts appear to have been about 800' in length and 180' in overall width, all three broken by an entrance about mid-way. They were destroyed by being 'hurled each into its foss and built over' (H W Young 1891). The enclosure measured about 1000' in maximum length and 600' in width. Excavation by Small of the higher court revealed that only a tiny portion near the Coastguard houses remained undisturbed. Sections through the remaining west rampart showed that the wall still stood some 10' high beneath a covering of sand. It is 27' to 28' wide and consists of rubble infill retained on either side by a carefully built revetting wall. None of the sections showed any evidence of domestic occupation, although temporary occupation was indicated during the Iron Age, Norse and Early Medieval periods. This agrees with the finds from Hugh Young's excavations in the early 1890's although he also found a Late Bronze Age spearhead (NJ16NW 31) and a Greek coin of Nero (54-68 AD).

The timbers which were thought to indicate timber-lacing of the walls are in fact probably supports for a wall-walk or other structures. Carbon 14 gives dates of AD 340 and 610 for them, and therefore, according to MacKie for the construction of the fort. He further assumes from this that it was built by the Picts in the early part of their period, and was not in existence during the Roman occupation of southern Scotland. It had previously been claimed as Roman and wrongly identified as Ptolemy's 'Pteroton Stratopedon'.

W Roy 1793; Proc Soc Antiq Scot 1890; Proc Soc Antiq Scot 1891; H W Young 1891; O G S Crawford 1949; J M Coles 1962; R W Feachem 1963; A Small 1966; E MacKie 1969.

Only very mutilated fragments of the fort remain as a result of the various excavations and general destruction, the best-preserved portion being the N rampart. Traces of the cross rampart running WNW/ESE are evidenced by occasional exposure of rubble construction. Some of the finds from Young's excavations are in National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland (NMAS), others are in the museum at the harbour master's office at Burghead.

Information from OS (W D J) 16 September 1963.

A Roman melon bead from this site is in NMAS.

A S Robertson 1970.

Burghead, promontory fort. Air photographs: AAS/97/12/G27/12 and AAS/97/12/CT.

NMRS, MS/712/29.

(Scheduled with chapel NJ16NW 6).

Information from Historic Scotland, scheduling document dated 25 September 1998.

A programme of archaeological research, survey and limited excavation was undertaken by CFA Archaeology Ltd in preparation for the production and installation of interpretation boards.

A topographic survey was carried out in order to accurately locate the positions of earlier excavations on the promontory. Watching briefs were maintained during the resurfacing of access tracks to the Coastguard houses and during excavation of foundations for four of the cairns on which display boards were to be mounted. However, no artefacts or archaeologically significant deposits were encountered.

Sponsors: Moray Council, Burghead Headland Trust & Historic Scotland

Information from Alexander, Ralston and Hicks 2001, CFA Report 636 (MS/1081/8)

NJ 109 691 At Burghead Fort, excavations were undertaken between February and April 2002, and a watching brief was conducted during further construction works between April and July 2002 in advance of the proposed construction of an interpretation centre within the 19th-century coastguard lookout. This lookout is set at the N end of the fort on top of the rampart which separates the upper and lower wards. The lookout is specifically excluded from the Scheduling of the fort.

The excavation of deposits within the lookout demonstrated that it had been built on top of extant rampart core material with little resultant disturbance of the rampart beneath. A section excavated through the rampart at this point demonstrated that it was stone-built of dump construction with no evidence for timber-lacing. The body of the rampart consisted of a mixture of large waterworn stones and apparently quarried sandstone with pockets of large beach pebbles, within a sand matrix. Fragments of sandstone were present throughout. There appeared to be little organised structure to the rampart's construction, although some variation could be seen within the rampart core; for example, pockets of beach pebbles were locally prevalent. Larger stones were visible towards the base of the section, with more voids present, perhaps indicating that a layer of basal stones had been laid on the ground surface initially to mark out the line of the rampart and/or provide a firm foundation for the rampart. The section of rampart excavated measured 8m wide (max.) and 3.00-3.25m high (max.). The excavation within the lookout did not extend through the inner or outer faces of the rampart due to the constraints imposed by working within the confines of that building. No artefacts were recovered.

Sealed beneath the rampart was a sequence of well-preserved organic deposits. Further excavation of these deposits showed that there were two old land surfaces separated by windblown sand, with relict dune sands beneath. These land surfaces were organic-rich and contained charred plant remains. No features were noted within these deposits.

Data Structure Reports deposited in the NMRS.

Sponsor: Moray Council for Burghead Headland Trust.

M Johnson 2002.

NJ 109 691 The key aim of this project in September 2003 was to identify and, if possible, date elements of the landward triple rampart system of the fort (NJ16NW 1), now located within the town and outwith the Scheduled areas of the monument. The total excavation of the garden of 22 Church Street proved negative; all finds were modern. In contrast, partial examination of the gardens of The Brae, 35 Grant Street, provided evidence for the cut of one substantial ditch below modern soil build-up, associated with the remodelling of Burghead and subsequently the erection in 1912 of The Brae. Standing walls limited the exposure of this ditch. A thin organic horizon associated with a small quantity of tumbled stonework contained no particulate charcoal and was not polleniferous.

A narrow trench was also machine-cut along the length of the footpath E of the enclosure holding the Burghead Well: whilst showing undulations in the subsoil, there were no clear surviving signs of a ditch here. However, it was noted that slight traces of two banks and ditches can still be seen on the surface trending obliquely across St Aethan's graveyard.

Archive to be deposited in Moray SMR and the NMRS.

Sponsor: Moray Headland Trust.

I Ralston 2004.

NJ 108 690 (centre) A watching brief was undertaken between March and May 2005 in the N part of the village of Burghead during water mains renewal, in the vicinity of a number of archaeological sites. Work revealed one possible archaeological deposit, a possible extension to the eastern rampart of the fort (NJ16NW 1).

Full report lodged with Moray SMR and NMRS.

Sponsor: Halcrow Group Ltd for Scottish Water.

S Farrell 2005.

Publication Account (1986)

The modern traveller, fighting for breath and warmth in a gale on the headland ofBurghead, may find it difficult to believe that he is standing in one of the most magnificent centres of Pictish power. Such was the destruction caused by the building of the present village in 1805-9, that the visitor must recreate in his mind the three great lines of rampart, with timber reinforcing, that stood 6m high and ran across the neck of the promontory from Young Street to Bath Street.

In 1809 the rampart that (most characteristically for a Dark Age site) formed the seaward defences was observed to consist of ' ... the most various materials, viz, masses of stone with lime, cement, pieces of pottery and baked bricks and tiles, half burnt beams of wood, broken cornices and mouldings of well-cut freestone .... On some pieces of the freestone are seen remains of mouldings and carved fIgures, particularly of a bull, very well executed .... [These were] the ruins ... of a considerable town'. The 'bull, very well executed' is a reference to the famous Pictish animal carvings from Burghead, of which six survive,* although between 25 and 30 are recorded in the literature.

A small stump of the innermost cross rampart survives in the 'Doorie Hill', the green mound on which sits the blackened mounting for the Clavie (the midwinter fIre-festival). The upper and lower wards of the fort also survive, the rampart of the latter being the best preserved (it is from this wall that evidence for nailing of the timber beams in the wall comes). In all, nearly 3 ha were enclosed, making Burghead one of the largest forts of any date in Scotland. The possibility that the boats of the Pictish 'navy' that carried the men of Moray in battle to Orkney sheltered beneath the headland cannot be ignored.

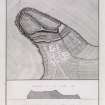

The Well is an elaborate subterranean rock-cut basin, with walkway around; it was damaged on discovery. Although described in the past as a 'Roman' well or an early Christian baptistry, its location in an elaborate Pictish fort suggests that its unusual construction is merely a reflection of the overall level of grandeur required by the inhabitants for their water supply. Alternatively, it could have functioned as a water shrine, ultimately of Celtic inspiration.

*Two are in Burghead Library, two are in Elgin Museum and the Royal Museum of Scotland and the British Museum have one each.

Information from ‘Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: Grampian’, (1986).

Publication Account (1996)

The modern traveller, fighting for breath and warmth in a gale on the headland of Burghead, may find it difficult to believe that he is standing in one of the most magnificent centres of Pictish power. Such was the destruction caused by the building of the present village in 1805-9, that the visitor must recreate in' his or her mind the three great lines of rampart, with timber reinforcing, that stood 6m high and ran across the neck of the promontory from Young Street to Bath Street.

In 1809 the rampart that (most characteristically for a Dark Age site) formed the seaward defences was observed to consist of, ' ... the most various materials, viz, masses of stone with lime, cement, pieces of pottery and baked bricks and tiles, half burnt beams of wood, broken cornices and mouldings of well-cut freestone .... On some pieces of the freestone are seen remains ofmouldings and carved figures, particularly of a bull, very well executed .... [These were] the ruins ... of a considerable town'. The 'bull, very well executed' is a reference to the famous Pictish animal carvings ftom Burghead, of which six survive, although between 25 and 30 are recorded in the literature. (Two are in Burghead Library, two are in Elgin Museum and the National Museums of Scotland and the British Museum have one each.)

A small stump of the innermost cross rampart survives in the 'Doorie Hill', the green mound on which sits the blackened mounting for the Clavie (the midwinter fire-festival ). The upper and lower wards of the fort also survive, the rampart of the latter being the best preserved (it is ftom this wall that evidence for nailing of the timber beams in the wall comes). In all, nearly 3 ha were enclosed, making Burghead one of the largest forts of any date in Scotland. The possibility that the boats of the Pictish 'navy ' that carried the men of Moray in battle to Orkney sheltered beneath the headland cannot be ignored.

The Well is an elaborate subterranean tock-cut basin, with walkway around; it was damaged on discovery. Although described in the past as a 'Roman' well or an early Christian baptistry, its location in an elaborate Pictish fort suggests that its unusual construction is merely a reflection of the overall level of grandeur required by the inhabitants for their water supply. Alternatively, it could have functioned as a water shrine or drowning pool, ultimately of Celtic inspiration.

Information from ‘Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: Aberdeen and North-East Scotland’, (1996).

Project (21 October 2013 - 23 October 2013)

NJ 1090 6914 A geophysical survey was carried out, 21–23 October 2013, in order to try to contextualise the promontory fort of Burghead as part of the Northern Picts: Archaeology of Fortriu project. A resistance and magnetic survey was undertaken in the upper and lower citadel of the fort. The main goal was to identify if there are any surviving features which may relate to the occupation of the fort. Six 20 x 20m grids were surveyed in both the upper and lower citadels. The gradiometry survey did not record any features. This may be due to the use of the citadel in the 18th–19th century, although there were extensive scatters of metal objects from more recent times. The resistance survey results were more promising and showed a number of anomalies in the upper citadel and lower citadels. Of particular interest are two areas of high resistance measuring in total c6–8m by 40m located on the S side of the lower citadel by the middle rampart. However, the results as expected, suggest extensive disturbance of the fort in modern times.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen, Development Trust, University of Aberdeen and Tarbat Discovery Centre

Gordon Noble and Oskar G Sveinbjarnarson, University of Aberdeen, 2013

(Source: DES)

Magnetometry (21 October 2013 - 23 October 2013)

NJ 1090 6914 Magnetometry survey.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen, Development Trust, University of Aberdeen and Tarbat Discovery Centre

Gordon Noble and Oskar G Sveinbjarnarson, University of Aberdeen, 2013

(Source: DES)

Resistivity (21 October 2013 - 23 October 2013)

NJ 1090 6914 Resistivity survey.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen, Development Trust, University of Aberdeen and Tarbat Discovery Centre

Gordon Noble and Oskar G Sveinbjarnarson, University of Aberdeen, 2013

(Source: DES)

Excavation (6 July 2015 - 10 July 2015)

NJ 1090 6914 As part of the Northern Picts Project surveys and excavations have been undertaken in an area stretching from Aberdeenshire to Shetland targeting sites that can help contextualize the character of society in the early medieval period in northern Pictland.

From the 6–10 July 2015 a number of test trenches were excavated in the gardens belonging to the Coastguard houses of Burghead Fort – the largest Pictish fort known. The trenches aimed to evaluate the survival of intact deposits within the upper citadel of the fort, which was seriously compromised by the construction of the 19th-century town of Burghead. The majority of trenches revealed only 19th-century finds overlying natural sand deposits within the upper fort. One trench (2 x 4m) in the eastern part of the Coastguard station gardens did however reveal the remains of a timber structure with floor/midden layers overlying. Within these layers fragments of a large rotary quern were recovered. The floor/ midden layers were partially removed in a 1m wide slot

revealing a series of postholes below. Charcoal of Scots pine was recovered from the posthole and dated to 430-650 cal AD. A few metres to the N a 1 x 2m trench was excavated. This identified an animal bone midden that extended to at least 1m deep below 19th-century destruction and a layer of paving. The animal bone mainly consisted of cattle bone and within the midden a fragment of a 9th-century Anglo-Saxon coin was recovered.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen Development Trust in association with the Tarbat Discovery Centre

Gordon Noble and Oskar Sveinbjarnarson – University of Aberdeen

(Source: DES, Volume 16)

Note (30 March 2015 - 30 May 2017)

This fort is situated on Burg Head, the large promontory jutting out into the Moray Firth from the southern shore, which has given its name to the planned village that now extends up its spine. Whereas the earlier village is shown on a plan drawn up by General William Roy in the 18th century outside the defences, the construction of the new village and its harbour at the beginning of the 19th century led to the extensive demolition of the ramparts. As a result, Roy's plan published in 1793 remains the best guide to the disposition of the defences, which comprise three main elements: an enclosure on the summit of the promontory; an annexe apparently springing from the summit enclosure to take in the lower terrace immediately above the shore on the NNE; and a belt of three ramparts probably with external ditches cutting across the neck of the promontory on the ESE. The summit enclosure measured at least 155m from ESE to WNW by 60m transversely (0.8ha) within a massive timber-laced wall, though its heavily disturbed remains only survive in the sector overlooking the annexe on the NNE, the ESE end having been levelled for the construction of the upper W corner of the village, and the whole of the southern flank demolished to make way for the new harbour in 1808-9; the entrance was in the middle of the ESE end. The N corner of the village likewise overlies the ESE end of the annexe, which extended beyond the ESE end of the summit enclosure and measured at least 190m in internal length, tapering westward from a maximum breadth of 70m (1.1ha). Its N wall survives as a massive mound of quarried rubble, but the W end has been entirely removed. The entrance was in the ESE end, which appears to have taken in the entrance to the well-known well or cistern. In plan, the sinuous course of the outer belt of defences appears to mimic the ESE end of the summit enclosure and the annexe, cutting off an area on the promontory measuring perhaps as much as 255m in length by 190m in breadth (3.2ha). All three were pierced by an entrance that mounted the slope to the NNE of the burial ground, in which faint traces of these ramparts can still be detected; notably the outermost rampart and ditch are the largest on Roy's drawn profile taken towards the S end above the harbour, possibly indicating that these defences represent several periods of construction. The way the outer defences seem to follow the line of the summit and annexe defences might indicate that they were an addition, but they may equally be earlier, responding to the underlying topography, now masked by the village, and indeed the position of the well. The differences in size of the outer ramparts noted by Roy may in any case indicate that the outermost was once a free-standing defence in its own right enclosing an area of about 4.3ha.

Since the construction of the harbour and the new village, which saw the discovery of numerous carved stones, many of them bearing incised Pictish depictions of bulls, six of which survive, but also including fragments of early medieval cross-slabs (see RCAHMS Canmore ID 16190), there have been repeated archaeological interventions, with excavations carried out in 1861 (Macdonald 1862), 1890-2 (Young 1891; 1893), 1966 (Small 1966; 1969), 2002 (Johnson 2002) and 2003 (Ralston 2004) and currently by G Noble. Finds at various times have included a Late Bronze Age spearhead (Proc Soc Antiq Scot 24, 379), a Roman melon bead, several late Roman coins and an Anglo-Saxon mount dating from about the 9th century. The sections through the walls revealed clear evidence of timber-lacing in some places, though not everywhere, and the use of iron spikes in the frame; some of the timberwork appears to have been incorporated horizontally in the wall faces.

Information from An Atlas of Hillforts of Great Britain and Ireland – 30 May 2017. Atlas of Hillforts SC2925

Excavation (22 June 2016 - 7 July 2016)

NJ 1090 6914 (NJ16NW 1) As part of the Northern Picts project surveys and excavations have been undertaken in an area stretching from Aberdeenshire to Shetland targeting sites that can help contextualize the character of society in the early medieval period in northern Pictland.

During a two-week season at Burghead, 22 June – 7 July 2016, a 10 x10m trench was opened over an area which had revealed floor deposits and a large animal bone midden in 2015. The trenches aimed to further evaluate the survival of intact deposits within the upper citadel of the fort, which was seriously compromised by the construction of the 19th-century

town of Burghead.

The trench revealed a large extent of a highly fragmented floor surface of a rectangular building c4m wide. The full length of the building was not identified as it went into the baulk on the NW side of the trench, but it extended for at least 4m NW/SE. Radiocarbon dating suggests the floor layer is 9th/10th century AD in date and the large animal bone midden found in 2015 appears to be contemporary. The animal bone midden was found on the N side of the building represented by the fragmentary floor layer.

The 9th/10th-century floor layer is underlain and adjacent to a series of postholes. One posthole underlying the floor layer in 2015 was dated to the 6th century AD. A whole series of additional postholes appears to relate to multiple phases – some appear to be associated with the floor layer while others appear to form part of a ring ditch roundhouse structure.

Only radiocarbon dating and post-excavation analysis will help tease out the patterns and plans of these postholes. Part of a post-medieval structure was also found in the SE corner of the trench.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen

Gordon Noble and Oskar Sveinbjarnarson – University of Aberdeen

(Source: DES, Volume 17)

Excavation (9 May 2017 - 19 May 2017)

NJ 1090 6914 (NJ16NW 1) As part of the Northern Picts and Comparative Kingship project excavation was carried out, 9–19 May 2017. During a two week season a 8 x 6m trench was opened over an area to the N of floor layers and structural features identified in 2016. A cobbled floor and a possible hearth were found lying above early medieval layers. Post-medieval/modern postholes/pits were also found in the upper stratigraphy. On the lower sand subsoil a number of structures were found. A low stone wall in the northern corner of the trench may be post-medieval, but other structures appear to be earlier in date. A sunken building was found in the western part of the trench. It was defined by deeply set oak planks on one side and a stone wall that arced around enclosing a sunken area. Inside possible post pads and traces of an internal wattle wall were identified.

In the eastern half of the trench a turf wall and floor layer represented another large building. The turf wall was around 0.6m wide and survived to a height of 0.3m. It curved around a stone-built hearth and a dark grey sand floor layer. Large pieces of burnt oak trunkwood were found in the floor layer and next to the hearth a pierced Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great was located. Fragments of iron sheet and other iron objects were also found on the floor layer. The building may have been remodelled with a lower floor layer and a possible secondary wall at the northern end. A possible ring ditch and a number of isolated postholes/pits were found underlying the two buildings that lay on the subsoil. Radiocarbon dating on charred cereals and charcoal from the various structures is in process.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen and Historic Environment Scotland

Gordon Noble and Oskar Sveinbjarnarson – University of Aberdeen

(Source: DES, Volume 18)

Excavation (9 April 2018 - 23 April 2018)

Season 1 of excavations within the scheduled area of Burghead, undertaken to date the enclosing elements and characterize the survival and use of the lower citadel. These excavations confirmed the fort was built and used in the early medieval period and was quite densely occupied by buildings of various sizes and shapes. This forms part of a wider project investigating the development of early medieval kingdoms in Northern Britain and Ireland (The Comparative Kingship project).

Information from OASIS ID: jamesodr1-407740 (J O'Driscoll) 2018

Excavation (1 April 2019 - 12 April 2019)

NJ 1090 6914 Further excavation at Burghead, 1-12 April 2019, continued investigations of settlement deposits located in the lower citadel in 2018 and aimed to further mitigate the effects of coastal erosion on the seaward end of the upper citadel (DES 2015, 125; DES 2016, 121; DES 2017, 134-5: Canmore ID: 16146).

Four trenches were opened. Trench 11 at the seaward rampart of the upper citadel showed exceptional preservation of the inner rampart wall face which now stands less than 1m from the active erosion edge – the outer wall face having already been lost in this part of the fort. The wall face stood to around 3m high and six layers of horizontal and transverse oak beams were identified, the upper three layers of which showed extensive evidence for destruction by fire. The rampart cut through old ground surfaces which were sampled to provide TPQ dates for wall construction. In Trench 13 floor layers of a building were found in an area previously tested by Alan Small. Finds from this trench included fragments of crucibles and other metalworking evidence. A further building with intact floor layers was found in Trench 14 located at the other side of the upper citadel, near to an entranceway recorded into the fort (now destroyed). Trench 18 in the lower citadel identified a very substantial wall that ran for at least 20m E-W and appears to be a side wall of a very large structure that ran parallel to the northern rampart of the lower citadel. At least 0.5m of occupation deposits were preserved on the northern side of this wall and the midden includes extensive numbers of well-preserved animal bones.

Archive: University of Aberdeen

Funder: University of Aberdeen

Gordon Noble; James O’Driscoll; Edouard Masson-MacLean; Cathy MacIver - University of Aberdeen

(Source: DES Vol 20)

OASAS id: jamesodr1-407742

Watching Brief (July 2019)

NJ 10866 69134 (centred) A watching brief was undertaken in July 2019 for a partial extension to the car-parking spaces close to the visitor centre, as part of scheduled monument consent at Burghead Fort (NJ16NW 88). Other than a few sherds of 19th/20th century pot, no archaeological remains or artefacts were discovered.

Archive: NRHE (intended). Full Report submitted to Highland HER and NRHE

Funder: Burghead Headland Trust

Stuart Farrell

(Source: DES Vol 20)

Excavation (August 2021 - September 2022)

NJ 1090 6914 The first two seasons of the HES funded Citadel project at Burghead were carried out over four weeks in total, excavation in August/September 2021 and 2022. Burghead Fort on the Moray Coast of Scotland is the largest and most complex early medieval promontory fort known in Scotland, one of fewer than 20 early medieval forts identified in Scotland and one of only three Pictish coastal promontory forts of this period, with the best-preserved defences of its type in Britain and Ireland. Yet significant parts of this site have been lost to development and now through coastal erosion. The Citadel project aims to mitigate further loss through rescue-led excavations on the eroding upper citadel of the fort in tandem with research- led excavations in the lower citadel and scientific analysis to provide unparalleled insights into the development and demise of an early medieval centre.

In both seasons of excavation, areas of the upper citadel

were targeted for 100% excavation in the areas that Alan Small excavated in the 1970s. In 2021, the upper citadel rampart was found to have completely collapsed into the sea in the area selected for excavation just to the W of the Coastguard Station cottages. However, areas of metalworking, postholes and settlement middens were found within the interior. Significant finds included a copper/alloy and iron composite bell – one of only around 20 found in Scotland to date, and 9th-century coins from Northumbria. In the lower citadel, in 2021, an area near the northern rampart was evaluated revealing partly truncated buildings, very extensive deposits of animal bone and working areas within the fort. Finds from the lower citadel included well-preserved bone pins, comb fragments, and a range of iron finds.

In 2022 the area of the upper fort excavated was located to

the N of the 2021 trench and uncovered a c5m stretch of the inner wallface of the rampart partly preserved, but right on the erosion edge. Almost 3m high of wallface was revealed including well-preserved evidence of the timber-lacing, the upper traces of which showed extensive evidence for destruction by fire. Within the interior further areas of midden and metalworking were found and notable finds included an iron spearhead and a stone- working chisel. In the lower citadel in 2022 excavations moved closer to the wallface of the northern rampart, and revealed much better preservation with the outline of one large sub-rectangular building with two hearths identified at the centre of the trench. At least two further structures were also revealed though walls were heavily disturbed and difficult to trace and/or mainly turf-built and thus not well represented. Finds in the lower citadel again included a range of well-preserved bone objects. Faunal remains were also very well preserved and included large deposits of fish bone and shell.

Archive: University of Aberdeen and NRHE (intended)

Funder: Historic Environment Scotland

Gordon Noble; James O’Driscoll; Edouard Masson-MacLean and Cathy MacIver – University of Aberdeen

(Source: DES Volume 23)

Environmental Sampling

An archaeological watching brief at Burghead Fort, Moray on the east side of the visitor centre at a former coastguard station, led to the discovery of two potential occupation deposits at the base of a small wall of unknown function on the east side of the tower and from the base of a retaining wall abutting the rampart. Bulk samples were taken from each of these deposits during the course of the watching brief for the retrieval of palaeoenvironmental and archaeological materials that may provide further information on the nature of these deposits.

A total of 2 bulk samples were taken during investigations of which both were processed for assessment.

Both samples were found to contain evidence of peatland plants relating to probable peat burning for fuel. The burnt peats may relate to the burning of prehistoric peats previously recorded at the site. Small quantities of burnt and unburnt mammal bone, together with marine shell from the samples may relate to discarded food waste.

Headland Archaeology Ltd.