Publication Account

Date 1951

Event ID 1097878

Category Descriptive Accounts

Type Publication Account

Permalink http://canmore.org.uk/event/1097878

86. Holyrood Abbey.

This house of Augustinian Canons was founded by David I in 1128. The legend of the foundation, which is given at the end of this article, simply repeats the story of the conversion of St. Hubert (656-727), which in turn is based upon the story of St. Eustace (c. 118); and it is no doubt discounted by the fact that an essential part of King David's cultural policy was the introduction of the Regular Orders into his realm. However that may be, once the foundation was made, the convent was drawn from the Augustinian house at Scone,* and Aylwin, who is prominently mentioned in the legend, was the first abbot. Until their new home was ready, the canons are said to have been lodged in Edinburgh Castle (1).

The site chosen for the Abbey was at the lower, or E., end of the rocky ridge that tails down from the Castle; it was fairly level, but had a slightfall from W. to E. The subsoil is blue clay and, until it was drained and cultivated in the 13th century, the place was in general marshy, unfertile and unhealthy. Even as late as 1507 there was a loch nearby, which had to be done away with before the gardens of the Palace could be laid out.

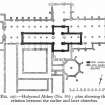

All that survives of the Abbey above ground is the ruined nave of the church, as repaired and consolidated by H.M. Office of Works in 1911. In the course of its work the Department exposed the foundations of the vanished choir and transepts, and these have been left open for inspection. The discoveries were planned at the time (Fig. 289 [SC 1030161]), and are interpreted here in a diagram (Fig. 290 [SC 1226986]) which makes the general arrangement clear. Within the area of the choir were unearthed the foundations of a separate building, which on account of its small size and of the burials associated with it - the majority of these were found on the S.E. - was then thought to be the remains of a Celtic church (2). Another explanation seems now more probable. Further excavation, carried out in 1924, proved that the foundations in question had extended beneath the present nave. Moreover, the latter has been constructed in sections, as if to encase some earlier building which was not removed until its successor was more or less finished-a normal procedure in the Middle Ages, when major buildings were invariably the work of successive generations. This fact, coupled with the further facts that this early building occupies the exact position in relation to the later one that would be expected in the circumstances suggested and that no pre-existing building is mentioned in the charter of foundation, points to the conclusion that we have here the last vestiges of the Abbey Church of 1128. If that is the case, the original structure was cruciform, and was unaisled except for a chapel aisle on the eastern side of each transept; there is no evidence that its E. end was apsidal. Its length is actually unknown, although shown in Fig. 290 as approximately 170 ft. The clear span of the nave and choir was 23 ft., and that of the transepts 1 ft. less. One of the doorways, which can be referred to the first half of the 12th century on the evidence of the architectural detail, was taken down and rebuilt as the E. entrance from the cloister into the S. aisle of the present nave when this came to be built in or about the year 1220. Nothing survives of the first cloister, but, like its successor, it was certainly on the S. side of the church.

In the latter part of the 12th century it was decided to rebuild the church upon a more sumptuous scale. In the scheme that ultimately came to be developed within the two succeeding centuries a new building arose, vaulted throughout, and square-ended. It comprised a nave of eight bays with western towers; N. and S. transepts, each of two bays and with an E. chapel-aisle; and an aisled choir of six bays including a Lady Chapel, two bays wide, which was flanked on each side by a chapel at the end of either aisle. To accommodate additional chapels, an outer choir-aisle was later thrown out on the S. side. There is reason to suppose that the crossing-tower was not carried above the high roofs. The architectural history of this second church, as reflected by the fabric, may be summarised as follows.

It is reasonable to suppose that reconstruction would begin with the conventual choir and transepts; their foundations, however, seem to have been removed to make way, as will appear, for a still later expansion of these parts. But the arrangement existing in the second half of the 12th century may have included an aisled choir of three bays with a central apse, and square transepts with eastern apsidioles. As regards the nave there is no uncertainty. Here, towards the last decade of the 12th century, building began on the outer wall of the N. aisle, and proceeded continuously until the string course below the aisle windows had been reached. The ground-course, however, was extended round the W. gable as far as the S. respond of the pier arcade. By the beginning of the 13th century the wall of the N. aisle had attained its maximum height; the W. gable and its doorway were progressing; and work on the S. aisle had already begun.** About 1220 the bases of the pier arcade were laid; this arcade, as well as the crossing-piers, had reached the triforium-level by the middle of the century, by which time the W. gable and W. towers had attained a similar height while the S. aisle had already been completed. The high wall-heads were probably ready for their vault about 1260. The next step was to vault the aisles - the ribs of the N. aisle are of a later section than are those of the high vault - and immediately thereafter, no doubt, the vault surfaces were covered with steeply-pitched wooden roofs, heavily slated.

By this time the late 12th-century choir and transepts were so far out of date that they had to be rebuilt in their turn, and from now onwards the architectural detail, which had so far been “international” in character, begins to assume features which are definitely native. The masonry shows that the rebuilding of the N. transept was not undertaken until some time after the nave vault had been turned, that is to say about 1275, and the choir with its two main aisles may be supposed to have followed successively; but these parts can hardly have been completed before the middle of the 14th century as the work must have been interrupted in 1322 by Edward II's forces. To the middle of the 14th century may likewise be attributed the earliest part of the S. transept, followed shortly afterwards by the S. outer aisle of the choir.

At length the church was again complete in all its parts and the remodelling of the conventual buildings could accordingly be undertaken. There is evidence that a new chapter-house, octagonal on plan, was built about 1400. Then the older part of the church fabric began to call for repair, for, although masonry and foundations were excellent, insufficient provision had been made for the vault thrusts and as early as the beginning of the 14th century preparation had to be made for additional support to the S. side of the nave. It was left to Abbot Crawford, however, in the second half of the 15th century, to overcome the danger by means of flying buttresses received on sturdy, lateral buttresses with heavy pinnacles. It may be assumed that by this time the parish had fully established its right to the nave, for the same abbot also made in the N. aisle, for parish use, a handsome new doorway with a benatura on its E. side, besides erecting a stone screen between nave and crossing. Before the century was out Abbot Bellenden, Crawford's successor, had "theikit the kirk with leid," and had effected 'some minor alterations on the wall of the S. aisle of the nave.

In 1544 Holyrood was burnt and looted by Hertford's troops, and on their return in 1547 the same troops stripped the lead from the church roofs. In 1570, when Adam Bothwell, Bishop of Orkney and Commendator of this Abbey since 1568, was charged before the General Assembly with neglect of the fabric, he pleaded poverty and proposed that, as the choir and transepts were now superfluous and ruinous-the two eastern crossing - piers being actually dangerous - he should pull these parts down and apply the money accruing from the sale of the material to the repair of the nave, the parish however sharing in the expense (3). This proposal must have been sanctioned, for the church was immediately reduced to its present dimensions by the closing-in of the arches at the pulpitum, and the erection of lofts to increase the seating accommodation. An alteration made to the great W. window may be ascribed to the same time.

In 1633 Charles I decided that his coronation should take place in the Abbey Church. But the place was then dark, incommodious and out of repair, and orders for its restoration were accordingly given "both for the credite of the countrie and for thes olemnitie of that important actioun." The Lords of Secret Council thereupon instructed the King's Masters of Work, Sir James Murray and Anthony Alexander, to take action with all diligence. The desks and lofts were to be removed; the E. gable was to be taken down and rebuilt with a "faire new window"; an E. window was to be placed in the N. aisle; the N. tower was to be made ready for a peal of bells; and the W. gable and door were to be repaired (4). The W. front was, in fact, finished off on baroque lines.

With the rising importance of the Palace the parishioners came to be ousted from the church in which they had long since acquired parochial rights, and when a new parish church came to be erected in the Canongate in 1687, the nave of the Abbey Church became officially what it had long been in practice, the Chapel Royal, and was sumptuously fitted out for this purpose. But in 1758, when the roof required attention, the Court of Exchequer voted £1000 towards its repair, and this spelled the destruction of the fabric. It was found that the roof timbers had decayed, and, to avoid the expense of renewal, the timber roof was taken down and the upper surfaces of the high vault were covered with heavy stone flags. The extra weight of the flags caused a thrust which Abbot Crawford's reinforcement was unable to withstand; and in the course of the next ten years the wall-heads were gradually pressed out until finally the vault and the clear storey crashed to the ground. Since then the nave has been a ruin.

[see RCAHMS 1951 for an architectural description and a note on the bells etc, 38 sepulchral monuments, and the foundation story]

RCAHMS 1951

(1) Lawrie, Early Scottish Charters, p. 383. Although this statement is accepted by Lawrie, it may not be well founded as it can be traced to no earlier authority than Father Hay. (2) O.E.C., iv, p. 193. (3) The Booke of the Universall Kirk of Scotland, pp.163 and 167. (4) P.S.A.S., i (1851-4), p. III.

*Scone, which had been colonised from Nostell Priory in Yorkshire, also colonised the Priory of St Andrews, (P.S.A.S., xlix (1914-5), p. 91).

**The aisle, which seems to be from the hand of another master-mason, was built more rapidly than its neighbour.